Clarke Square, one of Milwaukee’s most diverse, storied, and densely populated neighborhoods, dates back fifty years before Milwaukee became a city. In 1795 French-Canadian fur trader Jacques Vieau built Milwaukee’s first settler’s cabin there as part of his trading post overlooking the Menomonee Valley (a site marked in Mitchell Park).[1] In 1819 Vieau gave the post to Solomon Juneau, a French-Canadian trader he hired as a clerk. Juneau married Vieau’s daughter Josette in 1820 and became Milwaukee’s first mayor in 1846.[2]

Bounded by the Menomonee Valley, Cesar Chavez Drive (South 16th Street), Greenfield Avenue, and Layton Boulevard (27th Street), Clarke Square was named for Norman and Lydia Clarke. In 1837 they purchased 160 acres west of Walker’s Point, one of Milwaukee’s first three settlements. Called Clarke’s Addition, the area remained largely undeveloped for fifty more years. The Clarkes donated 2.1 acres for a park, which was named Clarke Square in 1890. Longfellow School (one of Milwaukee’s oldest public school buildings) dates to 1886.

In the mid-1800s magnate Alexander Mitchell developed a private park called Mitchell’s Grove overlooking the Menomonee Valley. The nascent Board of Park Commissioners acquired that parcel in 1890 for one of Milwaukee’s first major public parks.[3]

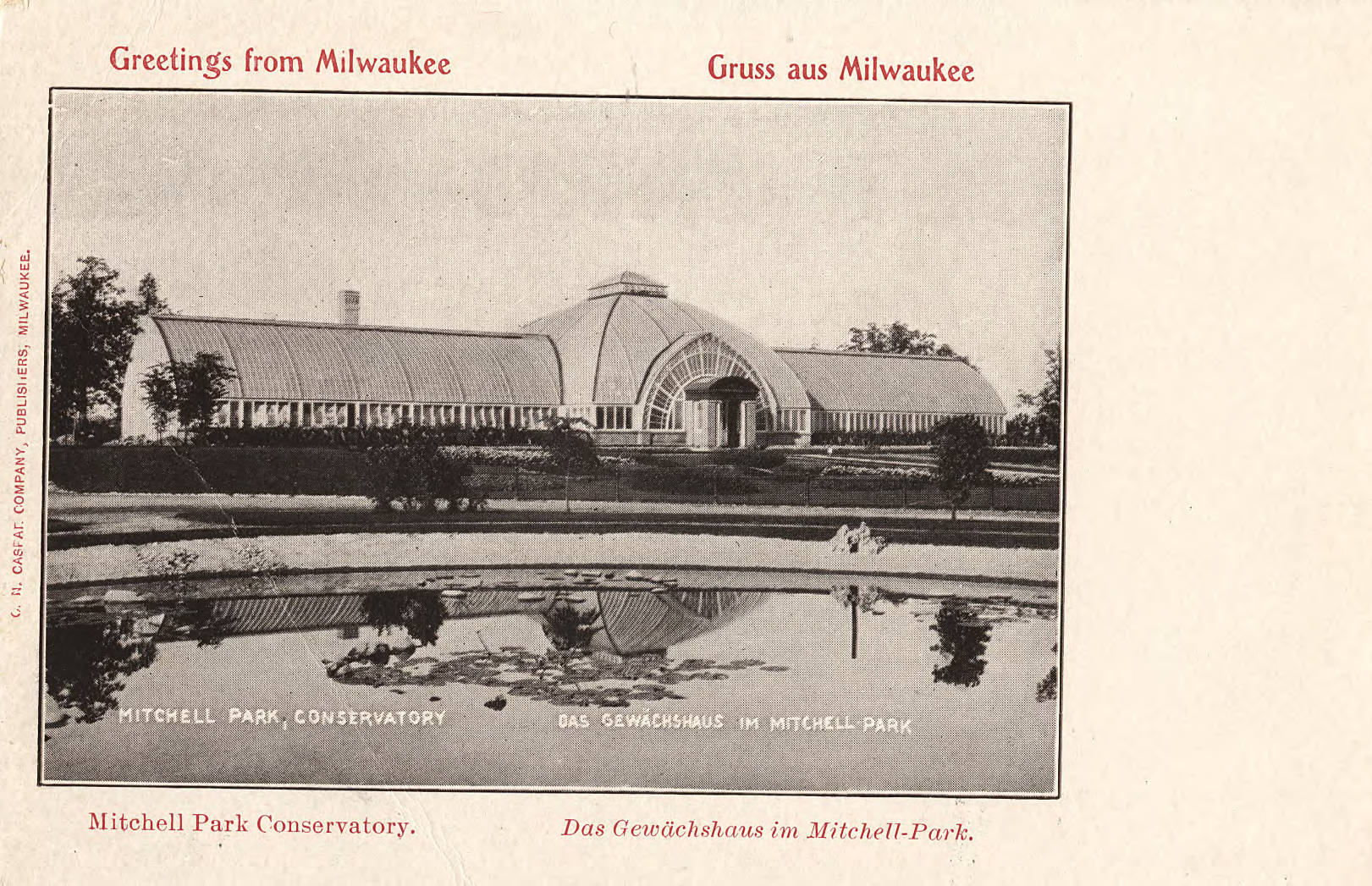

In 1898 Milwaukee architect Henry C. Koch designed the Victorian-style Mitchell Park Conservatory, which was demolished in 1955 after decades of neglect. A new conservatory—three cone-shaped “Domes” designed by Donald L. Grieb—was dedicated in 1965 by U.S. First Lady “Lady Bird” Johnson and soon became an iconic destination.[4]

Original Clarke Square settlers traced their roots to the British Isles, Germany, Scandinavia, and the eastern United States. The neighborhood eventually attracted Eastern European immigrants and people from other backgrounds. It became known for abundant churches (many still standing), tree-lined streets, and varied homes and commerce. Many early residents walked to work in nearby Menomonee Valley industrial jobs. Others were merchants and tradespeople.

The Great Depression hit the neighborhood hard. The long-time residential base began shifting after World War II. More Hispanic families, many related to tannery workers recruited from Mexico during the 1920s, began moving in. By 1990, Latinos comprised 35 percent of the neighborhood population; by 2010 the figure approached 70 percent. Southeast Asian immigrants, including Hmong from Laos, began moving there in the 1990s. The 2015 population was 8,038—Milwaukee’s fifth-densest neighborhood.[5]

Beginning in the 1970s, massive de-industrialization diminished employment opportunities citywide and distressed Clarke Square. Since then, virtually all of the Menomonee Valley’s 300-acre “brownfield” has been repurposed, including by new corporations and the Potawatomi Casino. The nonprofit Menomonee Valley Partners led the revitalization effort and collaborated with Urban Ecology Center to create the 24-acre Three Bridges Park in 2013, which connects to Clarke Square.[6] The Cesar Chavez Business Improvement District works to enhance that north-south connector. Multi-ethnic groceries and restaurants serve neighbors and visitors.

Journey House and Milwaukee Christian Center, both founded in the late 1960s, and the Southside Organizing Committee, launched in 1990, provide community services. Numerous churches address neighborhood needs, including Ascension Lutheran, St. Peter Evangelical Lutheran Church, and Prince of Peace and St. Adalbert Catholic parishes. The School Sisters of St. Francis, a century-long Clarke Square anchor, founded Layton Boulevard West Neighbors in 1995. In 2008 the Zilber Family Foundation catalyzed the Clarke Square Neighborhood Initiative. These and other groups collaborate to strengthen the neighborhood by focusing on community-established goals.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Narrative of Andrew Vieau, Sr., originally published in Wisconsin Historical Collections, vol. 11 (1888), published online by Wisconsin’s French Connections, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, last accessed October 22, 2018.

- ^ John Gurda, “Frontier Valentines: Living Proof That Love Can and Did Abide,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 7, 1999.

- ^ Harry Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space: Park Traditions in Milwaukee County,” Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, ed. Ralph M. Aderman (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987), 255-323.

- ^ John Gurda, “Summer under Glass: Mitchell Park’s Conservatory Preceded Mitchell Park Domes,” Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past (Madison, WI: Wisconsin State Historical Society Press, 2007), 153-155.

- ^ Overview of Clarke Square, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Statistical Atlas, last accessed October 22, 2018; Neighborhood Description [Clarke Square], 191 Milwaukee Neighborhoods website, last accessed October 22, 2018.

- ^ Menomonee Valley Partners, “Menomonee Valley’s New 24-Acre ‘Three Bridges Park’ Opens to Public Saturday July 20, 2013,” Urban Milwaukee, July 9, 2013, last accessed October 22, 2018.

For Further Reading

Schmid, John. “Lessons from History: Despite Crime and Poverty, Clarke Square Evinces an Entrepreneurial Spirit That’s High in Vibrancy and Dreams for the Next Generation.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 30, 2017.

Small, Virginia. “Transforming a South Side Neighborhood.” Urban Milwaukee, June 1, 2016.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.