Solomon Juneau’s trading post provided the first source of commodities for locals, with indigenous peoples as its earliest customers. After land sales in the mid-1830s drew hundreds, then thousands of Americans west of Lake Michigan, an early newspaper advertisement for Juneau’s shop listed cotton cloth, blankets, hatchets, saddles, looking glasses, rifles, and flints available in exchange for fur, skins, or cash. Competitors were soon offering tea, coffee, sugar, boots, pails, stoves, and farming hardware at their general stores.[1]

During these early decades, merchants typically focused on a single product line or a handful of related items. They operated out of simple, utilitarian structures, with upper floors providing offices and lodge halls. By 1847, Milwaukee featured “four book shops, three boot and shoe stores, approximately twenty butcher shops, a number of confectioners, nineteen dry good stores, three fur and cap stores, at least thirty retail grocers, eight hardware shops, and number wine and liquor stores.”[2] One well-known businessman during this era, John Black from Alsace-Lorraine, operated a dry-goods store on Water Street. He was known to warn his customers not to enter his shop unless they intended to buy something: window-shopping (so-to-speak) was unacceptable. Although most stores, especially the more refined, were located in a steadily evolving downtown area, other vendors chose neighborhood locations, including on Third and Twelfth streets as well as Mitchell Street.[3]

Department stores, per se, developed because of increasing population densities, the rise of centralized streetcar lines, fast-changing commercial practices, and an unbelievable growth in the range of consumer goods. Department stores typically had smaller markups, fixed prices, friendly return policies, and quick responses to changing tastes in fashions. Early “department” stores often housed multiple businesses under a single roof, with the owner acting as coordinator of space, inventory, and policy. T.A. Chapman was the individual who moved Milwaukee past this arcade approach to merchandising. He came to Milwaukee in 1857 after more than a dozen years of retailing in Boston. A sequence of buildings (including one designed by local architect Edward Townsend Mix) culminated in 1885 with a $150,000, four-story, Romanesque revival-style emporium complete with engravings, a grand staircase, a three-sided fireplace, and a skylight featuring four murals. Understanding how American department stores were becoming daytime havens for women with discretionary funds, by 1888 Chapman’s employed nearly three hundred workers, a majority female, possibly the first such business to do so in Milwaukee. By 1896, the store featured fifty departments, each with its own buyer, and catered to clientele from Michigan to North Dakota. Chantilly lace came in twenty patterns and parasols, in hundreds of variations, cost from seventy-five cents to twelve dollars.[4]

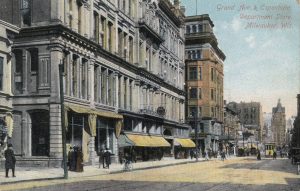

Competing entrepreneurs followed. After years of success in Vincennes, Indiana, the Gimbel family brought refinements to Milwaukee merchandising by pioneering bargain Fridays, extending liberal credit terms, offering free delivery, and advertising in both German and English newspapers. The foundation for this firm’s role in local history was literally solidified in 1902 with the opening of a Daniel Burnham-designed, eight-story white terra cotta building snugged up against the Milwaukee River at Grand Avenue and Plankinton. Additions on adjacent land to the south followed. The famous columned, riverfront face of this building was completed in 1925.[5]

Espenhain’s, eventually settling at Fourth and Grand Avenue, opened as a dry-goods store in 1879. Decades later, in the late 1920s, new management from out of state decided to reconfigure the store as the city’s chief bargain center, using the novel idea of allowing customers to choose their own items unassisted and then carrying these goods to a central cashier.[6] A.W. Rich and Company, which did not survive the nineteenth century, nonetheless did have its moments. It employed architect E.T. Mix to remodel its building with a skylight and large plate glass windows. Divided into thirty-four departments that included a book section and an art division, A.W. Rich featured a passenger elevator and overhead trolley baskets to move a customer’s goods.[7] Among the department stores not centrally located in downtown was a chain of Schuster’s stores, beginning in 1884. This firm eventually opened operations at Twelfth and Walnut, Third and Garfield, and Sixth and Mitchell.[8] Finally, the third attempt in Milwaukee to employ the Boston Store name succeeded under the management of Julius Simon, eventually settling in at Fourth and Grand Avenue in 1900. Over decades, the Boston Store pioneered methods that included phone orders during non-business hours and air delivery service along three routes across Wisconsin. The Boston Store was also a leader in updating the interiors of its main store. By the mid-1930s, amid the Great Depression, its renovations offered customers modern pillars and ceiling beams, recessed lighting, clean, spare lines in the aisles, and blonde display tables. The company was also cutting edge in opening a parking lot adjacent to its downtown store as early as 1923, attracting national coverage. Gimbels followed suit, negotiating with owners of a parking structure in 1929 for customer accommodations.[9]

This twentieth century phenomenon, the automobile, created a revolution in retail merchandising, especially in the post-World War Two era. Most downtown department stores joined the suburban exodus by opening anchor stores in the new wave of shopping malls that began with Southgate, a non-enclosed complex finished in 1951 along South 27th Street. Nonetheless, the postwar financial bleeding for downtown stores continued, forcing further innovations. As early as 1957, schematics were prepared to transform the CBD shopping district into a series of malls. One version was actualized in the 1980s with a futuristic development that unified all the stores along the south side of Wisconsin Avenue from Gimbels to the Boston Store under a single roof, anchored by a refurbished Plankinton Arcade. This strategy bought time, until economic conditions following the Great Recession required even more inventive reuses of Grand Avenue Mall space. The bankruptcy of the Boston Store’s parent company in 2018 further threatened the future of complex facilities such as department stores as well as big box stores in general.[10]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Chicago-Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1931), 415-16, 424, 431-32; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 31.

- ^ City of Milwaukee, Central Business District Historic Resources Survey (Milwaukee: Department of City Development, 1986), 3-6. Hereafter cited as CBDS.

- ^ William George Bruce, Builders of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Company, 1946), 70-71; Gurda, 134, 188.

- ^ CBDS, 11-15; Bruce, Builders of Milwaukee, 72-73; Landscape Research, Built in Milwaukee (Milwaukee: City of Milwaukee, 1983), 89; Richard Longstreth, The American Department Store Transformed, 1920-1960 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 22; Larry Widen, Vintage Milwaukee Postcards (Milwaukee: Apple Care Publishing Co., 2005), 69.

- ^ CBDS, 13-15; Widen, Vintage Milwaukee Postcards, 58, 59.

- ^ CBDS, 16-17.

- ^ Bruce, Builders of Milwaukee, 73-74; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 330-31.

- ^ CBDS, 17-19; Longstreth, The American Department Store Transformed, 42, 70, 89, 146, 274 footnote 19; Bruce, Builders of Milwaukee, 73.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 408-09; Longstreth, The American Department Store Transformed, 104, 190, 206, 224, 229, 248, 294 footnote 69, 296 footnote 125, 329, 384-85; Widen, Vintage Milwaukee Postcards, 108-09.

For Further Reading

Chan, Christopher. “Mass Consumption in Milwaukee: 1920-1970.” Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 2013.

Geenen, Paul H. Schuster’s & Gimbels. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012.

Lisicky, Michael J. Gimbels Has It! Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.