The African American community in Milwaukee dates from the earliest days of the city’s settlement, though the main story is found in the Great Migration—the mass exodus of black southerners to northern, industrial, urban centers through the twentieth century. The black population in Milwaukee remained very small throughout the nineteenth century and into the World War II era. By 1915, for example, the city counted only 1,500 black residents.[1] African Americans navigated the Jim Crow Era in Milwaukee in the same ways as many black communities around the country, small or large. Because of rigid patterns of residential segregation African Americans found themselves consigned to the “colored district” known as “Milwaukee’s Little Africa.” And, like many of these districts around the country, middle and upper class African Americans were locked into the area along with poor blacks and other racial and ethnic groups. In the face of both housing and job discrimination, self-help strategies and local institution-building served as the hallmark of black responses in a city that was defined by the promises of its industrial landscape. During and after World War II, economic opportunities in industrial work opened and Milwaukee’s black community grew rapidly, reaching some 40-45% of the city’s population in the early twenty-first century.

By the new millennium residential segregation, racialized criminalization, employment bias, eventual unemployment, and poverty would plague Milwaukee’s black community and dominate the city’s public discourse. However, Milwaukee’s black community sustained a rich history of resistance to patterns and practices associated with racial inequality. Indeed, this persistent struggle peaked in grand fashion during the 1960s when the March on Milwaukee for fair housing played a key role in shaping federal legislation of the civil rights era.

Early Years of Black Milwaukee

The establishment of the city of Milwaukee and the state of Wisconsin coincided with the national controversies over the abolition of slavery in the 1840s and 1850s and the coming of the American Civil War. As a result, antislavery politics and the rights of African Americans were very much part of the early political debate of the city and state, even as the number of African Americans in the local area was tiny, only a few hundred. There were high profile incidents in the 1840s and 1850s of local residents of Milwaukee and Waukesha, black and white, helping runaway slaves Caroline Quarlls and Joshua Glover avoid slave catchers and escape to Canada. On the other hand, local black residents faced patterns of discrimination in voting and employment in the frontier city.[2]

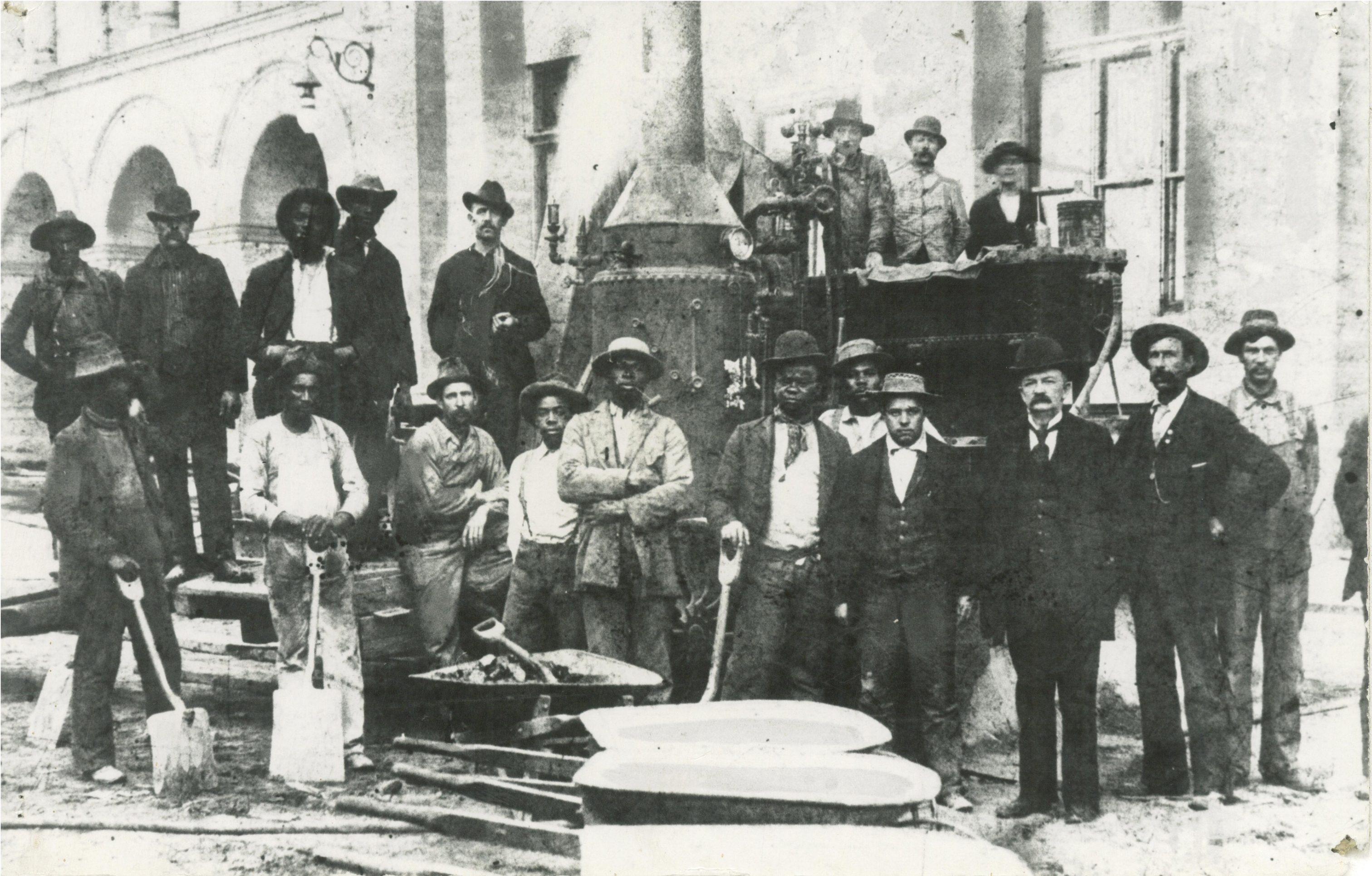

The formal emancipation of the American slave population and the reconstruction of the South in the 1860s and 1870s, however, did not lead to significant migration to Milwaukee, or much improvement in the social and economic position of Milwaukee blacks. Most black residents worked primarily in “service” and as common laborers, with a very small number in a middle class of proprietors or professionals. The community reached almost nine hundred by 1900, as the city grew to some 285,000 residents.[3]

Despite these small numbers and the limitations imposed by the rising tide of Jim Crow segregation, Black Milwaukeeans pushed the state to pass the Wisconsin Civil Rights Act (1895), which banned discrimination in public establishments. Black Milwaukeeans were also instrumental in defeating a proposed anti-miscegenation bill of the period.[4]

Interwar Years, 1915-1945

As in other northern cities, however, World War I prompted rapid growth and new opportunities for African American communities. European immigration stopped, while demand for labor in war industries opened doors to industrial jobs previously barred to African Americans. By 1920 Milwaukee’s black population rose to 2,200, and a plethora of community institutions were born that decade, including the local chapters of the Urban League and NAACP in 1919. Prominent religious institutions at the time included St. Mark African Methodist Episcopal Church (founded in 1869), Calvary Baptist (founded in the 1890s), and the Roman Catholic St. Benedict the Moor (founded in 1908 as a Capuchin mission).[5]

The 1920s saw even more in-migration. The community expanded rapidly again to 7,500 by 1930, producing what historian Joe Trotter has called a black “industrial proletariat.” The city’s emerging “colored district,” expanded to State St. on the South, North Avenue on the North, Third Street on the East, and Twelfth Street on the West.[6] Nevertheless, this district was not yet a “ghetto,” as a substantial majority of residents in the district were white, including a mix of Greeks, Jews, Slavs, and Bohemians. The small size of Milwaukee’s black community was also notable, only 1.2% of the total for the city. By 1930, by comparison, the black population of Chicago was almost 234,000; in Detroit, 120,000.

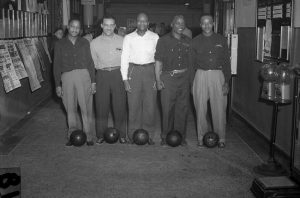

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, community building continued. Wilbur and Ardie Halyard found the Columbia Building and Loan Association to provide banking and home loan services to the black community.[7] J. Anthony Josey moved his newspaper operations to Milwaukee in 1925 as the Wisconsin Enterprise Blade.[8] And black entrepreneurs opened an array of small retail businesses to serve a community that faced discrimination in public accommodations from other city establishments.[9]

The Great Depression stopped further migration from the South and inflicted much hardship and unemployment on the city as a whole and the black community in particular. A return to robust industrial employment and prosperity did not materialize until the defense build-up of the Second World War. Black migrants who had come in the 1920s were at the bottom of the industrial ladder. They both faced historic race discrimination and were the last hired, and thus faced more layoffs as the industrial economy collapsed. In 1940, the white male unemployment rate in the city still hovered at 12.7 percent; it was 29.3 percent for black men; 21.6 percent of black men were employed in “emergency work,” through the relief programs of the New Deal.[10]

When war threatened in Europe once again, Milwaukee’s economy improved, and African Americans found jobs available in wartime industries. The city’s expanding industrial landscape beckoned more black southerners—the African American community grew to an estimated 10,000 by 1945[11]—setting the stage for significant socio-economic developments into the post-World War II era.

The Late Great Migration

The first century of African American life in Milwaukee is prologue to the massive second wave black migration, what scholars have called Milwaukee’s “late great migration,” which boosted the number of African American city residents to 22,000 in 1950 and 105,000 by 1970. In the 21st century the community reached about 220,000, or some 40 to 45% of the city population.[12]

By the end of World War II the numbers of blacks began to increase dramatically and the old systems of employment exclusion were met with an emerging black, urban proletariat that sought inclusion in the industrial job market. However, the patterns and practices that shaped residential segregation became nearly unmovable, and as growing numbers of new black migrants arrived they were immediately locked into nearby though expanded spaces that had previously been shaped by race and racialized public policy.[13]

From 1940 to 1970, Milwaukee’s African American population increased dramatically. During the 1940s Milwaukee added roughly 13,000 new African Americans to its “inner core”—the expanded area that housed most of the city’s black population. Milwaukee’s “inner core” mirrored other industrial urban spaces where southern migrants settled and became known more for its economic challenges and blight than the rich cultural expressions and entrepreneurial endeavors that also defined the area.[14] The 1950s and 1960s, though, highlight the demographic explosions of the Second Great Migration with Milwaukee emblematic of the continued migratory patterns of black southerners. To no surprise, black migrants headed to cities that continued to hold the promise of industrial employment. As one such city, by 1960 Milwaukee’s black population had ballooned to well over 60,000. As the city embarked upon the 1970s—having said goodbye to Hank Aaron and the Milwaukee Braves who moved to Atlanta in reverse-migratory irony—Black Milwaukee had grown to nearly 106,000 residents.[15]

But as the numbers of black people increased, a familiar, now infamous set of historical patterns played out in Milwaukee as it did elsewhere. Droves of whites steadily sought refuge from the growing numbers of blacks in nearby, surrounding and oftentimes newly-formed racially exclusive suburbs. And while federal laws and Supreme Court opinions began to ban outright race discrimination in housing in the post-war era, more sophisticated, race-neutral policies emerged to complement the efforts of real estate agents and lending institutions still clinging to and buttressing patterns of residential segregation that evolved into the metro area’s hyper-segregation of the twenty-first century. That hyper-segregation in turn limited the full integration of the African American community into the economic, political, and social life of the region.

Yet, blacks in the Brew City resisted such injustices, and they did so in ways that speak to the discourse associated with debates concerning the “long civil rights movement.”[16] Blacks in Milwaukee resisted labor exclusion. They resisted delays and timid approaches to school desegregation, in demonstrations, lawsuits, and the creation of community schools. They skillfully resisted willful police violence and brutality. And, they challenged residential segregation in dramatic fashion with over two hundred nights of marches that demanded open housing on a non-racial basis. With an increasing number of blacks arriving into the 1950s and 1960s, civil rights upsurges in the Brew City also lasted into the 1970s, given the persistence of issues that became even more glaring as the black population continued to grow.[17]

Once the black freedom struggle transitioned from the protest era to political engagement (i.e. protest to politics) into the 1970s, black leaders and activists in Milwaukee also sought to impact and shape the course of political decisions that impacted their communities. By the end of the 1960s local activists continued to engage in policy-making and decision-making processes on an array of issues impacting inner core neighborhoods. Milwaukee residents worked to ward off the unrelenting poverty clearly on the horizon. As one example, black people tried to mitigate the destructive forces of urban renewal by attempting to steer the outcomes of redevelopment projects through community engagement. Black leaders, activists, and concerned citizens from local chapters of the Urban League, NAACP and many local organizations shaped a vibrant set of local movements that defined the civil rights era. These efforts continued in interesting ways throughout the 1980s while the city experienced the massive deindustrialization of one of the nation’s most vibrant industrial hubs.[18]

By the new millennium, black Milwaukee had grown to over 220,000 residents who face a set of systemic challenges directly tied to race and segregation that have produced unrelenting poverty and devastating unemployment. As but one descriptor, from 1970-1990, as the city-suburb dichotomy became defined by racial hyper-segregation, Milwaukee lost 14,000 industrial jobs. Meanwhile, the city’s suburban municipal counterparts gained more than 100,000 new industrial jobs.[19] These trends have created staggering employment and unemployment realities for black Milwaukeeans. In 1970, nearly 74% of the black men in the city were employed. By 2009 only 46.7% of black men were employed. This 53.3% non-employment rate is double 1970 unemployment figures. Similarly, by 2009 only 56% of black men in their prime working years were employed. Just 40 years prior, 85% of black men in their prime working years were employed. By 2009 only Detroit had a higher jobless or non-employment rate for black men of working-age.[20]

Milwaukee’s industrial base experienced a precipitous decline over this period, as did much of the nation. Across the country, as regional economies dipped and unemployment soared, black workers faced the brunt of the industrial decline. Significant black inclusion into industrial labor markets was still a relatively new phenomenon by the time the nation began full-scale deindustrialization. In fact, just as the 1960s and 1970s welcomed black workers into industry, thanks in large part to federal and state fair employment codes and employment-based litigation, the nation had already begun the steep decline of its industrial core. Black workers, only recently having found a place in industry, were often the first to be laid-off or downsized due to limited seniority. Similarly, black workers continued to struggle for significant protections from organized labor. As the children of black industrial workers saw their parents earn decent wages in the 1960s, 1970s and to some degree the 1980s, they arrived into adulthood in cities that no longer held the promises of jobs that paid a livable hourly wage with plenty of overtime to accrue. Instead, for many the post-industrial, urban landscape was one that needed escaping because of the limited economic opportunities it presented. Milwaukee’s industrial decline is as much a national story as it is a local one, and it is one that helps to explain the economic doldrums black people face in many cities across the nation.

The convergence of deindustrialization, suburbanization, and racial segregation has “systematically diminished the employment prospects” for blacks in Milwaukee since 1970. In fact, when compared to other post-industrial cities, Milwaukee’s employment crisis is one of the most disturbing and presents no immediate signs of abating. However, while much of the employment crisis is correctly attributed to deindustrialization, Milwaukee’s job decline is indeed an urban-specific problem. While “industry” in general has sought cheaper labor in markets outside of the U.S., the suburbs of metro-Milwaukee have experienced astonishing job growth since the 1970s and 1980s—including industrial employment—while the city experienced decline. On this point, one statistic stands out among the many: studies over the past several years show that 96.3% of the men employed in suburban-based manufacturing jobs are white. Beginning as early as 1980, black male joblessness in Milwaukee has been significantly higher than that of white males in the suburbs.[21]

These statistics reflect important demographic shifts in the metro Milwaukee (urban/suburban) region over the last half-century. In 1970, the overwhelming majority (85.6%) of working-age men living in Milwaukee were white. By 2005, Milwaukee’s working-age male population had become majority-minority, due largely to white flight to surrounding suburbs and the growth of the city’s Latino population. In 1970 Milwaukee could brag of having the lowest jobless rates for black males in comparable cities, but by the new millennium it had one of the highest unemployment rates amongst its peers.[22] Race and residential segregation have had clear negative outcomes on the employment opportunities for African Americans.

Milwaukee’s fifty-year battle over the desegregation of public education and school reform also continues in the twenty-first century. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported in 2014 that “one in three” students in Milwaukee Public Schools, “attends a school that is intensely segregated, defined as any school with an enrollment that is at least 90% one race. Nearly 20 years ago, that number was far smaller: less than one in 8 students.” They continued by noting that, “School districts in Waukesha, Washington and Ozaukee counties have all become more diverse in their enrollment in the past 20 years. But none of those counties, on average, educates a population that is less than 82% white.”[23]

While poverty, unemployment and hyper-segregation limit the life options for black Milwaukeeans, racial bias in the criminal justice system has also greatly impacted African Americans. Wisconsin, fueled by the criminalization apparatus in Milwaukee, has the highest black male incarceration rate in the nation. In fact, African American communities have always experienced higher levels of crime and policing, per capita, than white ethnic families living in surrounding neighborhoods. Milwaukee’s black communities have had to consistently respond to and counter racialized perceptions of urban crime in the local press and from local and state government. And while local leaders and activists raise opposition to these patterns and practices, working to impact the criminal justice system from within or pressuring the system for change from without, several of Milwaukee’s black communities have experienced a level of criminalization that leads many to name the impact a public health crisis that teeters on the brink of human rights violations.[24] These challenges though are not specific to Milwaukee and reflect a national crisis in urban, black communities. Yet, few cities offer more glaring outcomes and indices associated with these challenges than Milwaukee.

As African Americans in Milwaukee entered the 21st century facing glaring challenges and indices, local leaders and grassroots activists remained committed to the tradition of resistance to injustice and support within the community that marked the 20th century. In this newer era, community leaders molded a non-profit industry that looks to address these very challenges. Maybe most impressively, several social entrepreneurs revolutionized urban farming and wellness practices, reconnecting residents to sustainable food cultivation. A wide array of civic and religious organizations work to decarcerate the state’s penal industry and reform local policing practices. And, local activists continue to negotiate for equitable educational options and developmental programs for the city’s youth. On matters concerning African Americans, urban-suburban geopolitics, and sustained community organizing and resistance to racial inequities, Milwaukee African American community will continue to shape and provide important lessons.[25]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Thomas R. Buchanan, “Black Milwaukee, 1870-1915” (master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1974); See also Jack Dougherty, “African Americans, Civil Rights, and Race Making in Milwaukee,” in Margo Anderson and Victor Greene, eds. Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 134.

- ^ Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-1945, 2nd ed. (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007), xxvii-li.

- ^ Trotter, Black Milwaukee, 3-33.

- ^ Dougherty, “African Americans, Civil Rights, and Race Making in Milwaukee”; Leslie H. Fishel, Jr., “The Genesis of the First Wisconsin Civil Rights Act,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 49, no. 4 (Summer 1966): 324-333.

- ^ Trotter, Black Milwaukee, 31.

- ^ Trotter, Black Milwaukee, 67.

- ^ Trotter, Black Milwaukee, 97-98; Genevieve G. McBride and Stephen R. Byers, “The First Mayor of Black Milwaukee: J. Anthony Josey,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 91, no. 2 (2007): 2-15; Genevieve G. McBride, “The Progress of ‘Race Men’ and ‘Colored Women’ in the Black Press in Wisconsin, 1892-1985,” in The Black Press in the Middle West, 1865-1985, H. Lewis Suggs, ed. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996), 325-48.

- ^ Trotter, Black Milwaukee, 81-110.

- ^ Trotter, Black Milwaukee, 153.

- ^ Trotter, Black Milwaukee, 149.

- ^ The phrase “late great migration” is from Paul Geib. See Paul Geib, “From Mississippi to Milwaukee: A Case Study of the Southern Black Migration to Milwaukee, 1940-1970” Journal of Negro History, 83 (4) (1998): 229-48; and Paul Geib, “The Late Great Migration: A Case Study of Southern Black Migration to Milwaukee, 1940-1970” (master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1993).

- ^ Dougherty, “African Americans, Civil Rights, and Race Making in Milwaukee.”

- ^ Patrick D. Jones, The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009).

- ^ Jones, Selma of the North.

- ^ Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past,” Journal of American History 91, no. 4 (March 2005): 1233-1263.

- ^ On schools, see Jack Dougherty, More than One Struggle: The Evolution of Black School Reform in Milwaukee (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004). For policing protests, see Simon Ezra Balto, “‘Occupied Territory’: Police Repression and Black Resistance in Postwar Milwaukee, 1950-1968,” Journal of African American History 98, 2 (January 2013): 229-52.

- ^ Niles Niemuth, “Urban Renewal and the Development of Milwaukee’s African American Community: 1960-1980” (master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014).

- ^ Dougherty, “African Americans, Civil Rights, and Race Making in Milwaukee,” 138.

- ^ Marc Levine, “The Crisis Deepens: Black Male Joblessness in Milwaukee, 2009,” (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Center for Economic Development, October 2010), last accessed December 14, 2018. Levine distinguished the unemployment rate from the “jobless” or non-employment rate. The latter includes a measure of people who were not considered to be in the labor force according to the definition of unemployment measured by the federal government, because, for example, they were incarcerated or had given up looking for work. It provides a better measure of the impact of economic distress on the local population.

- ^ Marc Levine, “The Crisis of Black Male Joblessness in Milwaukee: Trends, Explanations, and Policy Options,” (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Center for Economic Development, March 2007).

- ^ Levine, “The Crisis of Black Male Joblessness in Milwaukee.”

- ^ Erin Richards and Lydia Mulvany, “60 Years after Brown v. Board of Education, Intense Segregation Returns,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 17, 2014, last accessed October 26, 2018.

- ^ John Pawasarat and Lois M. Quinn, “Wisconsin’s Mass Incarceration of African American Males: Workforce Challenges for 2013” (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Employment and Training Institute, 2013); Balto, “‘Occupied Territory.’”

- ^ For indications of these new initiatives, see for example, “Young Farmers,” Groundwork Milwaukee, last accessed December 14, 2018; “Wisconsin Political Activists Hope a ‘Silent Canvass’ Will Win Back Black Voters,” August 19, 2018, NPR Weekend Edition Sunday; accessed August 27, 2018; BLOC: Black Leaders Organizing for Communities, accessed August 27, 2018; Close MSDF [Milwaukee Secure Detention Facility], accessed August 27, 2018.

For Further Reading

Dougherty, Jack. “African Americans, Civil Rights, and Race Making in Milwaukee.” In Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past, edited by Margo Anderson and Victor Greene. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Dougherty, Jack. More than One Struggle: The Evolution of Black School Reform in Milwaukee. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Geib, Paul. “From Mississippi to Milwaukee: A Case Study of the Southern Black Migration to Milwaukee, 1940-1970.” Journal of Negro History, 83, no. 4 (1998): 229-48.

Jones, Patrick D. The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Trotter, Joe William, Jr. Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-1945, 2d ed. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007; originally published 1985.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.