Throughout most of its history, the Milwaukee area has been characterized for its manufacturing and blue collar heritage that molded much of its character. The industrialization that began after the Civil War required the muscles and brains of thousands of working people; to fill the demands of production. Budding entrepreneurs encouraged workers to come to the city and nearby communities from the East and from abroad.[1]

The new workers were paid hardly enough to maintain a decent home and to feed their families, even though they labored six days a week, usually ten to twelve hours a day. It was inevitable that these workers would soon band together to seek ways to improve their working conditions, increase their pay and, most urgently, to seek shorter workdays. Workers and their collective efforts—usually expressed through organized labor unions, but also coming from spontaneous efforts—have contributed to make the area what it is today.

The earliest signs of workers joining together to protest came in 1847, when some forty masons and bricklayers struck on a demand to increase their wages from $1.50 to $1.75 a day, and the following year when journeymen coopers protested against the reduction in the rate for making flour barrels. Labor disputes continued into the mid-1850s, but few brought any lasting improvements for the workers.[2]

After the Civil War, the demand for the eight-hour workday unified many unionists well into the 1880s, becoming the focus of the worker campaigns.[3]

A short-lived national labor organization, the Order of the Knights of St. Crispin, was founded in Milwaukee in 1867 among workers in the shoemaking industries. The Milwaukee lodges experimented in forming production cooperatives, but the effort failed, partly due to the Panic of 1873, and eventually the Knights died out.[4]

Milwaukee trade unions began to grow in the late 1870s in response to the increase in industrial production and used various means to win their demands, including strikes, boycotts, and the holding of mass meetings or rallies. Successful strikes occurred in the iron and steel mills, on the docks, with seafarers, in the railroad shops, and in the printing trades. In July 1880, three unions formed the Milwaukee Trades Assembly, pledging that the “wise concert of power” among the unions was needed to overcome the resistance of well-heeled employers. The Assembly expanded quickly and a few months later held its “First Annual Picnic and Festival” at the Milwaukee Garden. The attendance was over 2,000 persons, one of the largest gatherings in the city up to that point, according to the Milwaukee Sentinel.[5]

It was during this period that organized labor—represented by the Trades Assembly—began to look to political action to achieve goals that eluded them through more direct action against employers. In the spring 1882 elections, it entered a complete slate in collaboration with the Democratic Party and won all three major positions in city government, plus other races.[6]

Meanwhile the Knights of Labor entered Milwaukee in 1880, and its chief organizer, Robert Schilling, became perhaps the pre-eminent labor leader in the state.[7] The Central Labor Union, formed in March 1886, under the leadership of Paul Grottkau, soon dislodged the Knights and became the dominant labor federation in the city.[8]

In May of 1886, workers engaged in an eight-hour-day march were fired on by the state militia at the Bay View Iron Works, resulting in the deaths of seven workers.[9] The Bay View Massacre impacted organized worker activities, prompting most union leaders to concentrate on political action to achieve goals. Schilling proclaimed after the Massacre that “the intelligent citizens have a weapon mightier than the ball or the bayonet—the ballot.” The unions led in organizing the People’s Party that scored big victories in elections of 1886 and 1887. The victory was short-lived, however. The People’s Party lost virtually all of its earlier gains as the Democrats and Republicans formed a “Fusion Committee” to win back its majorities.[10] But the die was cast; workers and union activists found new power through politics and many unionists turned to the Socialist Party as the twentieth century drew near.

Frank Weber, a onetime shipyard carpenter, led in organizing the Federated Trades Council in 1887 as successor to the Central Labor Union; he was a socialist and worked with Victor Berger (later to become a Socialist Congressman) to steer the new Federation and eventually the Wisconsin State Federation of Labor (formed in 1893) to support socialist positions.[11]

The support of the unions was vital to the collaboration of Milwaukee Socialists and the Progressive Republicans of Gov. Robert M. La Follette that made the “Wisconsin Idea” and its series of progressive legislation of the early twentieth century a reality.[12] Unionists also provided the core of support for the Socialist Party that finally gained control of city government in 1910, the first major city in the United States to be governed by Socialists.[13] It ushered in some 50 years of practicing the “sewer socialism” that gave the city a reputation of clean, efficient government, evidenced by the fact that Time magazine on April 6, 1936 put Mayor Daniel Hoan’s face on its cover with the statement that “under him Milwaukee has become perhaps the best-governed city in the U.S.”[14]

With production increasing during World War I as well as with new organizing zeal, union membership nearly doubled to 35,000 by 1920. The “Roaring 20s,” however, saw employers increase their tactics to weaken trade unions, stepping up the use of private detective agencies and spies and of the use of injunctions to halt worker actions. By 1932, membership in the city was down to 20,000—the same as in 1913.[15]

With the Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, employment in Milwaukee County dropped by 44% from 117,658 in 1929 to 66,010 in 1933, while the sum total of wages dropped nearly 65% in the same period.[16] Encouraged by the 1932 election of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the beginning of the New Deal, labor unions shed their acquiescence of the 1920s and worked to assert control over their workplaces. FDR’s National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 guaranteed the right of workers to organize, and the impact was dramatic.[17] Membership in the American Federation of Labor locals in the County jumped nearly threefold to more than 50,000 by the end of 1934. These newly organized union members flexed their power by striking, with 107 walkouts involving 27,000 workers in 1934. A strike against The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company (TMER&L) by the conductors and mechanics who operated the streetcars affected the entire County, disrupting service but also bringing out crowds of supporters and demonstrators. The union won recognition, which ended the strike, but not before one demonstrator was electrocuted.[18]

In spite of the slowdown in the economy in 1937, the new unions were not reluctant to go on strike to force their employers to recognize the union or to win wage and benefit improvements. More than 50 strikes occurred in Milwaukee in 1937, with 20 of those being sit-down strikes that were eventually declared illegal by the U.S. Supreme Court.[19]

By the end of the 1930s, union membership in the area had jumped fivefold to more than 100,000, with virtually every major plant unionized.[20] In smaller cities near Milwaukee, as early as 1933, workers began unionizing. In Washington County, Carl Griepentrog, an electrician by trade, tells of organizing his company in 1937 in West Bend, which spurred workers in other nearby plants to do the same.[21] In Waukesha County, 21 workers organized at Waukesha Engines in September 1933 and within a month had over 200 members; they eventually formed Machinists Local 1377, which soon had members in a number of area plants.[22] Employers were hardly receptive, and many workers gained labor agreements only after striking. In Waukesha, West Bend, and Hartford, the unions were deeply involved in local politics and in community organizations.

When the United States mobilized to fight the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) after the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, Milwaukee’s recognized status as the “machine shop of the world” made its industries and workers vital to providing the parts that were critical to the success of the troops in the field, the sailors at sea, and the pilots in the sky.[23]

Workers who had flocked to unions during the 1930s joined in the patriotism of the times and accepted heavy overtime assignments to assure production; their parent federations (the AFL and CIO) and national union leadership joined with employers to sign no-strike and no-lockout pledges.[24] In many cases, unions and management worked jointly to assure the success of war bond sales, blood drives, and contributions to the city’s Community Chest campaigns.[25]

In spite of their patriotic fervor, unions found they still needed to represent their workers on issues like wages, the pace of work, overtime hours, and other conditions, while many companies sought to resist any inroads by unions into managing company policies.[26] Some disputes were resolved through conciliation or eventual referrals to the War Labor Board. Yet 51 strikes occurred in Milwaukee industries during the war, nearly all brief walkouts of four days or less.[27]

The war also brought women into the industrial workforce in large numbers to replace the workers going off to war. Most at first faced open hostility, suspicion, and apprehension from male workers. One survey showed that during the war at least 50% of all workers were female in nine of eighteen large plants studied; but in nearly every case, the officers of the union were male.[28] For women, the experience laid the foundation for a growing role for women, both in the shop and in union leadership. Some became longtime leaders, such as Florence Simons, of UAW-AFL Local 322 at Globe-Union, and Nellie Wilson, who by 1960 became the first African-American woman elected to the Smith Steelworkers Directly Affiliated Local 19806’s executive board.[29]

In the postwar period, the alleged role of Communists who had proved to be valuable in organizing many Milwaukee unions during the 1930s provided employers an opportunity to discredit the unions. This played out in the 1940-41 and 1946-47 strikes of United Auto Workers Local 248 and the giant Allis-Chalmers Mfg. Co. in West Allis and may have affected the November 1946 elections. Many voters may have been affected by possible Communist influence in the union and elected a Republican to a usually-safe Democratic Milwaukee Congressional seat and Joe McCarthy to the U.S. Senate. (McCarthy soon began his notorious anti-Communist crusade, since discredited as “McCarthyism.”)[30]

Nonetheless, Milwaukee unions grew and solidified their positions in most of the city’s workplaces. By the mid-1950s more than 40 percent of workers were unionized. Labor became unified in Milwaukee on September 30, 1959 when the CIO Council and the Federated Trades Council were merged to form the Milwaukee County Labor Council, now the Milwaukee Area Labor Council.[31] Milwaukee’s public employees, too, formed unions in the 1930s, most flocking to the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees that had been founded in 1932 in Madison. Even though they had no collective bargaining rights, blue collar public workers such as truck drivers, laborers, and other trades formed locals, some of which had nearly 100% membership in their units. The militancy of some units—such as those among garbage workers—brought annual confrontations with Milwaukee politicians and likely helped provide the impetus for the eventual passage of Wisconsin’s public employee collective bargaining law in 1959.[32]

From 1920 to 1945, the African-American population of the city went from 2,229 to an estimated 10,200; at first, most Milwaukee unions responded coolly to the influx, fearing blacks might undercut their jobs and be used as strikebreakers. Twice before, in the Illinois Steel strike of 1919 and the Milwaukee Road strike of 1920, attempts to bring in black workers as strikebreakers were thwarted when Socialist Mayor Dan Hoan heeded labor appeals to persuade employers to halt the practice. Yet as more black workers entered the workforce, many unions began to support their goals for equal treatment either by initiating them into their locals or by establishing separate locals.[33] The industrial-based unions of the CIO became the most progressive; by the 1960s the AFL unions—many of them from the construction trades—embraced enlightened practices. In the early years of the twenty-first century, African Americans were elected to the top two leadership positions in the Milwaukee Area Labor Council.

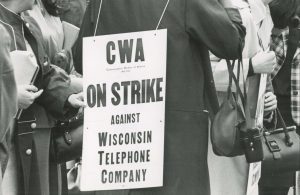

During the relative prosperity of the years up to 1980, the Milwaukee labor unions were able to steadily improve wages, benefits, and conditions, often employing strikes that usually were settled relatively quickly. The movement became an accepted part of the community as a major participant in the annual Community Chest (later the United Way) drives and a determining force in the Democratic Party that controlled City and County governments. Rarely did a candidate for mayor or county executive win in office without significant labor support; most of the candidates for city alderman and county supervisors needed support of the Milwaukee area’s labor council to win elections.[34]

After 1980, Milwaukee trade unionists faced the exodus of manufacturing from the area, with the loss of some tens of thousands of jobs from 1980 to 2010, most of them union. Even with the loss of membership, unions retained significant influence in city and state politics, representing a large bloc of voters and monetary support for Democrats. Many believe the major motivation for the Republican-controlled Legislature in 2011 to pass Gov. Scott Walker’s bans on public employee collective bargaining in Act 10 stemmed from the desire of Republicans to cripple the Democrats politically.[35] Milwaukee unionists responded in force, joining the thousands that came to Madison in the cold winter of 2011 to oppose the anti-labor actions by the Republicans.[36] The effort was not successful, as the Republicans pushed through Act 10. In early 2015, Gov. Walker and the State Legislature acted to weaken private sector unions with legislation that restricted union security clauses and weakened prevailing wage laws on state projects.

In spite of the new legislative barriers, Wisconsin labor leaders are not giving up and seem inspired to look for various ways to effectively represent the interests of working people.[37] Pro-worker advocates in the area have looked to other strategies, such as through the work of Voces de la Frontera, a Hispanic civil rights group which has drawn on trade union principles, and Wisconsin Jobs Now, a group working with union organizers in the $15-an-hour minimum wage campaign and to rally low-income workers. For many, the future strength of the labor movement in Wisconsin and Milwaukee may depend upon how actively unions are able to associate their causes with those of other groups, such as those fighting for civil, economic, or environmental justice, even if such groups are not structured as traditional labor unions.[38] History has shown that working people joining in collective action—whether through labor unions or other workers’ organizations—have contributed to progress in the Milwaukee community and to better lives for all and will likely do so in the future.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 128.

- ^ Thomas Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965), 7.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 14-18.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 21-22.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 35-42.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 43-45.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 46-50.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 55-56.

- ^ The number of deaths attributed to the militia action has varied; sources vary, ranging from six to ten.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 158-160.

- ^ Robert W. Ozanne, The Labor Movement in Wisconsin: A History (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1984), 40-41.

- ^ Elizabeth Jozwiak, Speech before the 30th Annual Conference of the Wisconsin Labor History Society, Madison, April 16, 2011 as reported in Newsletter: Wisconsin Labor History Society 29 no. 1 (Summer 2011). Also Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 111.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 158.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 302.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 126-137.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 277-278.

- ^ The NIRA was ruled unconstitutional in May 1935, but by July 5, 1935 workers’ right to organize and bargain collectively was spelled out when President Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 290-291.

- ^ Darryl Holter, ed., Workers and Unions in Wisconsin: A Labor History Anthology (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1999), 128.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 294.

- ^ Holter, Workers and Unions in Milwaukee, 103-105.

- ^ Ray Terry, “The History of Local 1377 of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers,” unpublished paper.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 308.

- ^ Richard L. Pifer, A City at War: Milwaukee Labor during World War II (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2003), 20-30.

- ^ Pifer, A City at War, 26.

- ^ Pifer, A City at War, 16.

- ^ Pifer, A City at War, 94.

- ^ Pifer, A City at War., 127-130.

- ^ Jamakaya, Like Our Sisters before Us: Women of Wisconsin Labor (Milwaukee: The Wisconsin Labor History Society, 1998). Oral interviews of Simons and Wilson are among ten summarized in this book.

- ^ Stephen Meyer, “Stalin over Wisconsin”: The Making and Unmaking of Militant Unionism, 1900-1950 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992), 163-186.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 201.

- ^ Kenneth Germanson, Oral History Interview by Michael Gordon, July 16, 2009 at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 32-33, last accessed May 31, 2017.

- ^ Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-1945, 2nd edition (Urbana and Chicago IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007), 44-66.

- ^ Based on the author’s personal experiences as a newspaper reporter (1957-62) and later union representative.

- ^ Mary Bottari, “The Sale of Wisconsin,” in It Started in Wisconsin, ed. Mari Jo Buhle and Paul Buhle (London and New York, Verso, 2011), 39.

- ^ John Nichols, “Introduction: Why Wisconsin,” in It Started in Wisconsin, ed. Mari Jo Buhle and Paul Buhle (London and New York, Verso, 2011), 6

- ^ Kenneth Germanson, “Overturning 100 Years of Progressivism: The Genesis of Anti-Unionism in Wisconsin,” presentation to North American Labor History Conference, October 24, 2015, Detroit, MI. Published as “Historical Look at How Wisconsin Lost Its Progressivism,” Advoken’s Blog, October 20, 2015, 13, last accessed May 31, 2017.

- ^ Will Jones, Professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, in presentation to Wisconsin Labor History Conference, April 11, 2015, Madison, WI, as reported in Wisconsin Labor History Society Newsletter 33, no. 1 (Summer 2015).

For Further Reading

Buhle, Mari Jo, and Paul Buhle, eds. It Started in Wisconsin: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the New Labor Protest. London and New York: Verso, 2011.

Gavett, Thomas W. Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. 1965.

Gurda, John. The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999.

Holter, Darryl, ed. Workers and Unions in Wisconsin: A Labor History Anthology. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1999.

Jamakaya. Like Our Sisters before Us. Milwaukee: Wisconsin Labor History Society, 1998.

Meyer, Stephen. “Stalin over Wisconsin”: The Making and Unmaking of Militant Unionism, 1900-1950. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992.

Ozanne, Robert W. The Labor Movement in Wisconsin: A History. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1984.

Pifer, Richard L. A City at War: Milwaukee Labor during World War II. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2003.

Still, Bayrd. Milwaukee: The History of a City. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin. 1948.

Trotter, Joe William, Jr. Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-1945. Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. 1985, 2007.

See Also

Explore More [+]

Understory

Writing about Workers’ Movements in Milwaukee

The development of this entry was an interesting challenge: how do I channel nearly 175 years of a vibrant, complex and fascinating movement of people into about six pages of type? Whether I have successfully done so, it’s hard to say. Many will be disappointed by what was left out; others will question what was included.

The main point of the entry was to show the importance of workers’ movements in the making of the Milwaukee area. Much of what is typically written about Milwaukee history emphasizes the industrialists, entrepreneurs, or political leaders as being responsible for building this great city and its environs; much less is written or taught in our schools about the working people who did the day-to-day work required to get the job done and the sometimes grueling and difficult circumstances in which they labored and the environments in which their families existed.

In their quest to improve their working lives and the well-being of their families, workers found they had to organize to press for changes, and as they did they helped to mold the area. They have left a great impact on the community. There were many human sacrifices and courageous actions made in this quest; likewise, there were likely mistakes, blunders and downright short-sighted actions made in the name of workers. Most worker organizations were the product of human beings, subject to all the foibles that emerge from such institutions. I hope the entry stirs in the reader a desire to search elsewhere to get the stories behind what is written here.

The reader, too, should be warned that the writer is an advocate for working people. I have been active most of my adult life in the trade union movement, as a member, local union leader, representative, official and, in later years, labor historian. Nonetheless, every effort was made to be objective in the tradition of the principles of truth that were part of my education at the University of Wisconsin journalism school; I followed these principles for 12 years as a reporter for daily and weekly newspapers at a time when publications were more dedicated to objectivity than seems to be the case in many contemporary media outlets.

The writer, too, has been involved in much of the history that covers the last sixty years of the entry. Thus, a small part of this entry actually is based upon my own experience, and for that I apologize. Such sections are noted in the footnotes. Nonetheless, I felt confident that those recollections were accurate and in perspective.

You will note, too, that I have relied heavily upon several books that have chronicled Milwaukee worker history, particularly Thomas Gavett’s Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, published in 1965 by the University of Wisconsin Press, which provides great detail on labor in Milwaukee from its earliest days through the 1950s. Unfortunately, this book is out of print, but it is available in most branches of the Milwaukee County Federated Library System. John Gurda’s popular The Making of Milwaukee, published in 1999 by the Milwaukee County Historical Society, pays close attention to workers, their unions’ history and their cultural and family life and is an invaluable resource as well.[1] Other valuable resources are listed in the “For Further Reading” section.

I welcomed the chance to write this entry, though it took far more time to develop than I thought it would. I hope readers will find it a useful introduction to the story of Milwaukee’s worker organizations.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.