Milwaukee has generated many social movements and controversies throughout its history. The following controversies have produced legal changes of lasting importance.

The Booth Cases (1854-60): In 1850, the U.S. Congress enacted a Fugitive Slave Act that imposed harsh penalties on persons who helped slaves escape to freedom.[1] The Act was deeply unpopular in Milwaukee and throughout the North. In early 1854, a mob led by abolitionist Sherman Booth broke into the Milwaukee jail and freed Joshua Glover, a recently-captured fugitive about to be returned to slavery in Missouri.

When federal authorities prosecuted Booth, his lawyer, Milwaukeean Byron Paine, applied to the Wisconsin Supreme Court for an order freeing Booth and holding that the Slave Act was unconstitutional. Paine argued that as a sovereign state Wisconsin need not follow earlier U.S. Supreme Court decisions upholding fugitive laws. The court agreed and freed Booth, thus launching a prolonged battle between Wisconsin and federal authorities that was not resolved until the eve of the Civil War.[2] Wisconsin was the only state that openly defied federal authority and refused to enforce the Act.

The Bay View Riots and the Origins of Wisconsin Labor Law (1886): In the late nineteenth century many Americans questioned unions’ legitimacy, believing that workers should only negotiate individually with employers. In 1886, a May Day rally of Milwaukee unions for an eight-hour day erupted in violence. Governor Jeremiah Rusk called out troops who fired on workers in Milwaukee’s Bay View neighborhood, killing at least five of them. Rusk condemned the unions and called on the legislature to restrict their activities, but legislators reacted more evenhandedly: they outlawed conspiracies among employers as well as workers, and they enacted several laws protecting unions’ organizing efforts. After the Bay View “riots,” Wisconsinites came to realize that workers’ right to act collectively was essential in an economy increasingly dominated by large corporations.[3]

The Bijou Theater Incident and Wisconsin’s Accommodations Law (1895): In 1883 the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a federal law prohibiting racial discrimination by theaters, restaurants, hotels and other businesses that accommodated the public.[4] The Court concluded that the federal Constitution did not authorize Congress to pass such laws but it left the door open for states to do so, and during the ensuing years many Northern states enacted their own accommodations laws.

In 1889 Owen Howell, a black Milwaukeean, was denied admission to a show at the downtown Bijou Theater when he insisted on being seated with whites. Howell and his attorney William Green, Milwaukee’s first African-American lawyer, sued the theater for discrimination and won. Green also urged the legislature to enact an accommodations law, and in 1895 he prevailed. Howell and Green were thus responsible for the enactment of Wisconsin’s first major civil-rights law.[5]

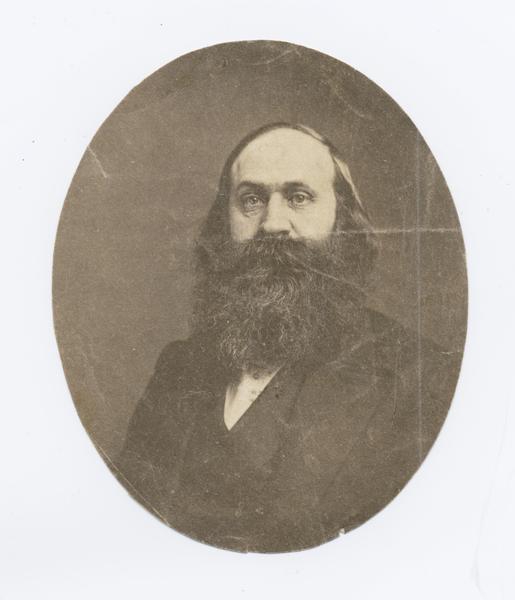

Victor Berger: A Martyr for Free Speech: Victor Berger (1860-1929) was a leader of the Social Democratic Party, whose members held Milwaukee’s mayoral post for all but four years between 1910 and 1940. Berger also published the Milwaukee Leader, one of the city’s leading newspapers, and in 1910 he became the first Socialist elected to Congress. Berger strongly opposed America’s entry into World War I. Federal officials used wartime anti-sedition laws to retaliate and Berger became the subject of two lawsuits that helped define the contours of free speech in America.

In 1917, after Berger published anti-war editorials in the Leader, the U.S. Postmaster General barred circulation of the Leader through the mails. Berger appealed but the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ban, a decision that some historians have called a low point for freedom of speech in America.[6] In 1918 Berger was tried for sedition, convicted, and sentenced to twenty years in prison. He appealed and in 1921, after the war ended, the Supreme Court overturned his conviction on a technicality; he was then allowed to resume his seat in Congress.[7]

School Desegregation (1963-1977): After African-Americans began moving to Milwaukee in large numbers in the 1940s, the city quickly became residentially segregated and the Milwaukee Public Schools’ (MPS) policy of promoting neighborhood schools led in turn to school segregation. Beginning in 1963 the Milwaukee NAACP, led by attorney and legislator Lloyd Barbee, engaged in boycotts and lobbied MPS to end the neighborhood school policy. When those efforts failed, Barbee filed a lawsuit asking for school desegregation. After more than ten years of litigation, Barbee won: in 1976 Milwaukee federal judge John Reynolds held that MPS had violated black students’ rights to equal protection of the laws, and he ordered MPS to develop a desegregation plan. But white Milwaukeeans steadily migrated to the suburbs at the end of the twentieth century, making it difficult to achieve Reynolds’ vision of a truly integrated school system.[8]

The School Voucher Program (1990): By 1990, many Milwaukeeans of both races had concluded that school integration was a failure. Black leaders wanted a system that would give them a greater voice in school operations, business leaders wanted competition between public and private schools, and Catholic leaders wanted state funding for parochial schools. As a result, in 1990 the legislature created a school voucher system for Milwaukee, the first such system in the nation, which allowed low-income parents to send their children to private schools at state expense.[9]

Public-school advocates challenged the new system, arguing that it violated constitutional guarantees of a uniform education and did not serve a public purpose. In 1992 a deeply-divided Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld the law by a 4-3 vote. Unlike Judge Reynolds, the court held that only equality of educational opportunity was required, not equality of educational settings.[10] In 1995 the legislature expanded the voucher program to include parochial schools, and in 1998 the Supreme Court rejected arguments that such expansion violated constitutional requirements for separation of church and state, thus ensuring that vouchers would become a permanent feature of Wisconsin’s educational system.[11]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ 9 U.S. Stats. 462 (1850).

- ^ See In re Booth, 3 Wis. 1 (1854), reversed, 62 U.S. 514 (1859); Ableman v. Booth, 11 Wis. 501 (1859); Alfons J. Beitzinger, “Federal Law Enforcement and the Booth Cases,” Marquette Law Review 41 (1957): 7.

- ^ Robert C. Nesbit, The History of Wisconsin. Vol. III, Urbanization and Industrialization, 1873-1893 (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1985), 387-412; Robert Hunter, Violence and the Labor Movement (New York: Arno Press, 1969), 68-19; Thomas W. Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965), 57-71; 1887 Wisconsin Assembly Journal 15-16 (January 13, 1887).

- ^ Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883).

- ^ Leslie H. Fishel, “The Genesis of the First Wisconsin Civil Rights Act,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 49 (Summer 1966): 327-32.

- ^ United States ex rel. Milwaukee Social Democrat Publishing Co. v. Burleson, 255 U.S. 407 (1921); Zechariah Chafee, Jr., Free Speech in the United States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941), 298-305.

- ^ Berger v. United States, 255 U.S. 22 (1921); see Sally M. Miller, Victor Berger and the Promise of Constructive Socialism, 1910-1920 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1973).

- ^ Amos v. Board of School Directors of City of Milwaukee, 408 F.Supp. 765, 821 (E.D. Wis. 1976), affirmed, 539 F.2d 625 (7th Cir. 1976), vacated and remanded, 433 U.S. 672 (1977); Frank A. Aukofer, City with a Chance (Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Co., 1968), 105-144.

- ^ 1989 Wis. Laws, ch. 336; John F. Witte, The Market Approach to Education: An Analysis of America’s First Voucher Program (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 43-46.

- ^ Davis v. Grover, 480 N.W.2d 460 (Wis. 1992).

- ^ Jackson v. Benson, 578 N.W2d 602 (Wis. 1998), certiorari denied, 525 U.S. 997 (1998).

For Further Reading

Aukofer, Frank A. City with a Chance: A Case History of Civil Rights Revolution. Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Co., 1968.

Baker, H. Robert. The Rescue of Joshua Glover: A Fugitive Slave, the Constitution, and the Coming of the Civil War. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2006.

Miller, Sally M. Victor Berger and the Promise of Constructive Socialism, 1910-1920. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1973.

Ozanne, Robert W. The Wisconsin Labor Movement: A History. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 1984, reprint edition 2014.

Witte, John F. The Market Approach to Education: An Analysis of America’s First Voucher Program. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.