In the spring of 1993, approximately 400,000 people fell victim to what Milwaukeeans have since referred to as “Crypto.”[1] At least sixty-nine people—mostly people suffering from AIDS—died in this Cryptosporidium outbreak, which would become the country’s largest waterborne disease epidemic on record.[2] These numbers do not include those who visited Milwaukee and drank the water before leaving, such as the college hockey teams in town for the NCAA tournament who left the city with an obscure pathogen in their bodies.[3]

When thousands of people in Milwaukee and its surrounding suburbs began suffering from flu-like symptoms that spring, no one knew why. Hundreds of patients overwhelmed emergency rooms in early April with complaints of vomiting, abdominal cramps, and dehydration, while officials remained in the dark as to what might be causing such widespread illness.[4] Pharmacies scrambled to restock anti-nausea medications as customers cleared the shelves.[5] The situation at area schools reflected the extent of the illness’s spread, as attendance dwindled and staff shortages prompted at least one closure.[6] As of April 6, the Milwaukee Health Department had not identified the source of the outbreak, but officials denied that the epidemic was connected to the city’s water supply.[7] Lab staffs at area hospitals had been testing stool samples for bacterial pathogens, but the scope of the outbreak led scientists to focus on protozoan infections, especially Cryptosporidium.[8] The following day, samples examined in County labs revealed the presence of this microscopic waterborne parasite.[9] That night, Mayor John O. Norquist announced the labs’ findings and told residents to begin boiling their water.[10]

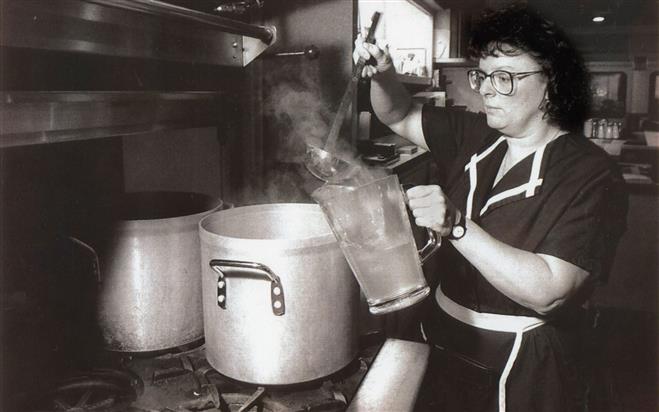

While people throughout the city fell ill, most cases were clustered on the South Side. Those who consumed water from the southern water treatment plant got sick at twice the rate of those who received their water mainly from the northern plant.[11] This information led officials to shut down the filtration plant serving the South Side. Unfortunately, the move came too late and the water containing the tiny parasites flowed freely through Milwaukee’s water supply system.[12] The boil advisory remained in place for an entire week, forcing the school system to throw away 68,000 servings of potentially dangerous Jell-O, while customers at Miss Katie’s diner declined water with their meals, despite waitresses’ promises that it had been properly boiled.[13] Several weeks after the ordeal, officials revealed that a flawed water quality control process had allowed the pathogen to breach the plant’s filtration system.[14]

In 2012, years after the outbreak and the reform to the water system that followed, residents of Milwaukee received a municipal services bill which included a special report from the Milwaukee Water Works identifying the city’s water as, “of the highest quality in the United States.”[15] Cryptosporidium cases have continued to appear in the area, but Milwaukee’s drinking water has not been identified as the source in any cases since 2000.[16]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Don Behm, “Milwaukee Marks 20 Years since Cryptosporidium Outbreak,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 6, 2013, accessed February 1, 2014.

- ^ Neil J. Hoxie et al., “Cryptosporidiosis-Associated Mortality Following a Massive Waterborne Outbreak in Milwaukee, Wisconsin,” American Journal of Public Health 87 (December 1997): 2032-2035.

- ^ Don Behm, “Milwaukee Marks 20 Years.”

- ^ Joe Manning, “Raging Virus Hits Hard at Area Schools.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, 1A, April 6, 1993, accessed April 13, 2016.

- ^ Joe Manning, “Raging Virus,” 11A.

- ^ Joe Manning, “Raging Virus,” 11A.

- ^ Joe Manning, “Raging Virus,” 11A. The official cited here was Milwaukee Health Commissioner, Paul W. Nannis.

- ^ Jeffrey P. Davis, “The Massive Waterborne Outbreak of Cryptosporidium Infections, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1993,” in Outbreak Investigations around the World: Case Studies in Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Mark S. Dowrkin, ed. (Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett, 2010), 197-199.

- ^ William R. Mac Kenzie et al., “A Massive Outbreak in Milwaukee of Cryptosporidium Infection Transmitted through Public Water Supply,” The New England Journal of Medicine, no. 3 (July 1994): 1, accessed December 28, 2014.

- ^ Gretchen Schuldt, “Boil Water, Mayor Says Safety of Drinking Water Probed in Wake of Mysterious Epidemic.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 8, 1993, accessed December 28, 2013.

- ^ William R. Mac Kenzie et al., “A Massive Outbreak in Milwaukee.”

- ^ Don Behm, “Milwaukee Marks 20 Years.”

- ^ Don Behm, “Milwaukee Marks 20 Years.”

- ^ Don Behm, “Milwaukee Marks 20 Years.”

- ^ Don Behm, “Milwaukee Water Works Says Drinking Water of Highest Quality,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 27, 2012, accessed January 12, 2014.

- ^ Don Behm, “Milwaukee Marks 20 Years since Cryptosporidium Outbreak.”

For Further Reading

Dowrkin, Mark S., ed. Outbreak Investigations around the World: Case Studies in Infectious Disease Epidemiology. Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett, 2010.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.