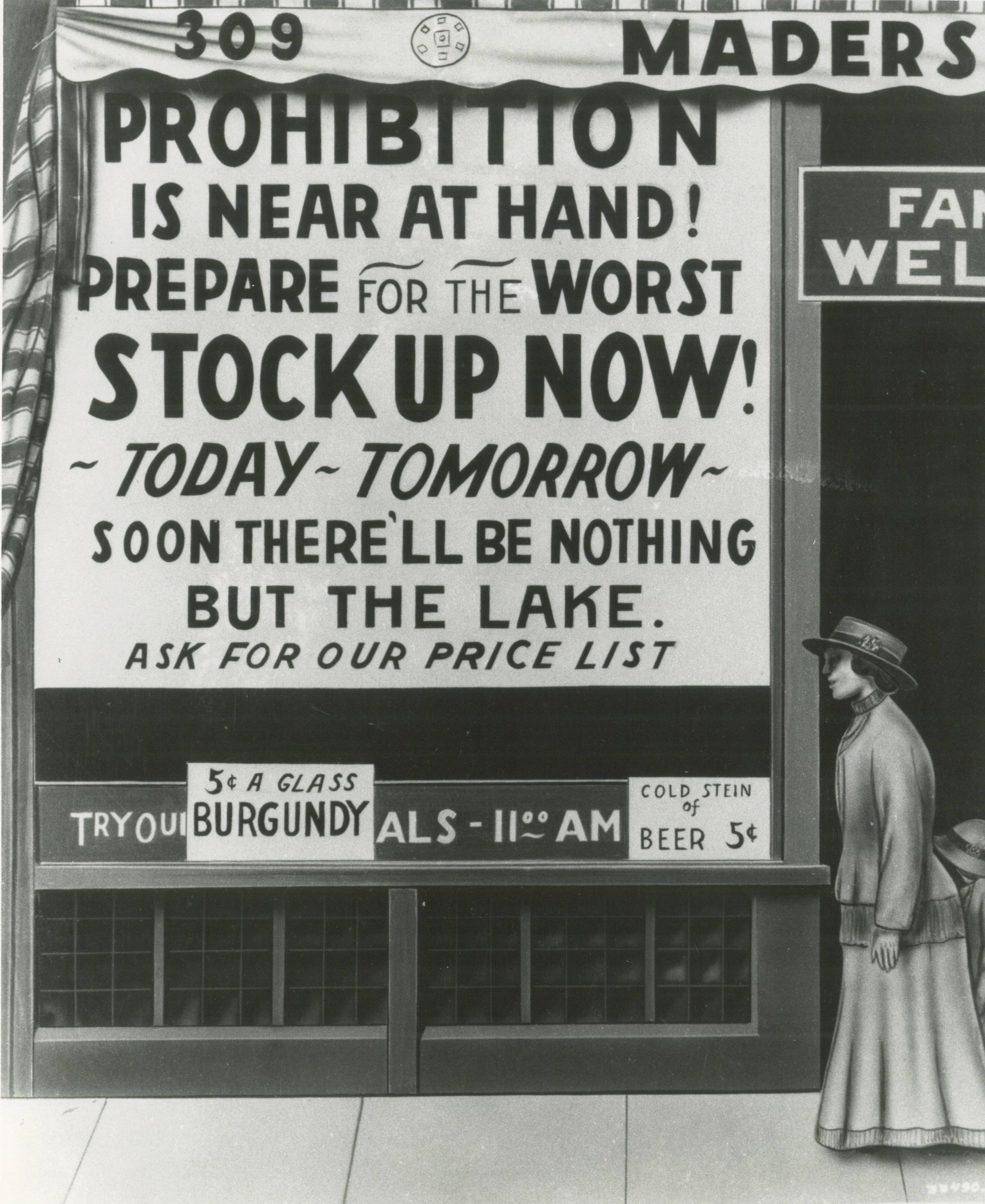

Due to efforts by the temperance movement in general and groups like the Anti-Saloon League in particular, alcohol consumption became a political issue following the American Civil War. Aided by growing anti-German sentiment following the outbreak of World War One, the prohibition movement—or a ban on the production, sale, importation, and transportation of alcohol—gained support among Progressive Era activists. In late 1917, the U.S. Congress finished its work on proposing a prohibition amendment and then, over the next year, state legislatures ratified the Eighteenth Amendment. By 1919 national prohibition was a reality. In 1920 Congress passed the Volstead Act, clarifying what alcohols would be considered illegal and what punishments would be assigned for violating the new law. Locally, the state of Wisconsin passed the Severson Act, a law mandating that Wisconsin follow the Volstead Act. For the duration of prohibition (which lasted until 1933), Milwaukee residents used various methods to obtain alcohol while local politicians attempted to modify, and then overturn, prohibition laws. At the same time federal agents struggled to keep Milwaukee dry.

Enforcement of prohibition lagged, making it relatively easy for Milwaukee residents to find liquor in “soft drink parlors,” roadhouses on the outskirts of the city, or by making the beverage themselves. Pharmacists and doctors became a popular means through which residents of the city obtained alcohol, usually with prescriptions for a weak drug to be consumed with a pint of whiskey. Rumrunners from Canada used Lake Michigan to get their product to Wisconsin, with a majority of these goods going through Racine and Kenosha. Wealthier residents often went to roadhouses located along Blue Mound Road, such as the Club Madrid, owned by Sam Pick, the “king of the nightlife.” They also frequented resorts outside the city, in Muskego and Pewaukee, which required memberships. For locals, the Third Ward became a popular location for bootlegging. Italian residents used apples, potatoes, and cherries to make the mash used in alcohol. Upon completion, teenagers transported the alcohol to customers. Additionally, the padroni, as certain well-known members of Milwaukee’s Italian community were known, set up an intricate system. The padroni would hire a fourteen year old boy to drive, sometimes four or five times per week, to Lafayette, Indiana to pick up alcohol and bring it back to Milwaukee.[1]

Realizing the monumental task before them, federal agents generally took action only after a public outcry arose over lackluster enforcement. As complaints grew, federal agents publicized their “drives” to stop bootlegging, usually by carrying out a very public raid on several small producers and sellers. A limited budget hampered the ability of federal agents to stop bootlegging. At one point in 1921, the eastern district of Wisconsin had only one agent, although this number grew to seven within a month.[2] Even when arrested, bootleggers did not face serious punishment. In fact, some of the earliest bootleggers, whose sentences involved serving time in the city’s workhouse, formed a Bootlegger’s Row where the convicts had parties with steaks and whiskey.[3]

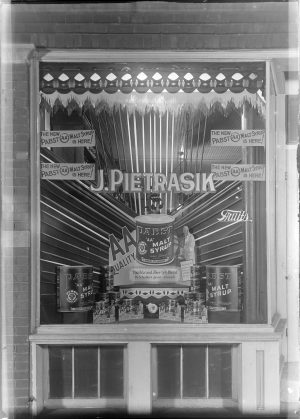

In 1918, the year before the Nineteenth Amendment became law, Milwaukee’s nine breweries employed over six thousand workers with an output valued at $35 million. Now, with the prohibition amendment, their jobs were under threat. To survive prohibition’s fourteen-year history, brewers became creative, shifting production to near beer, soda water, candy bars, cheese, and even snowplows![4] Opposition to prohibition, not surprisingly, became widespread throughout Milwaukee. The Sentinel editorialized against prohibition and its enforcement. In March 1920, the Milwaukee Common Council demanded that the American people be allowed to vote on whether the Eighteenth Amendment should become law. The council also suggested making low-alcohol beers and wines legal. It is worth noting, however, that not until the mid-1920s did the Sentinel or the council demand repeal of the prohibition law, preferring instead slight modifications. In 1922, several prominent Milwaukee residents formed the Wisconsin Anti-Prohibition Association, with Dr. J. J. Seelman as its president. Membership grew to over 2,000 within a month, and over 8,000 people attended a rally held at the Milwaukee Auditorium. Other groups, however, played an active role in making sure Milwaukee stayed dry. The Anti-Saloon League formed a branch of the Dry Enforcement League; the Milwaukee Rotary Club paid an agent to patrol the city; and the Ku Klux Klan looked for illegal activities.[5]

As opposition to prohibition in the Wisconsin legislation grew by the mid-1920s, Milwaukee socialists played a key role. Seven assemblymen and three state senators from Milwaukee, all socialists, led these efforts to repeal prohibition. Interestingly, a Republican from Milwaukee, Senator Bernard Gettleman, actually garnered the most attention, bragging that he made low-alcohol wine and beer in his home and holding a party where he served such beverages. Socialist Assemblyman Thomas Duncan, though, had the greatest impact upon prohibition in Wisconsin. While his efforts to modify the state’s prohibition law, the Severson Act, in 1927 experienced death-by-veto, Duncan introduced legislation in 1929 calling for a referendum on the state’s prohibition law. By a count of 350,337 to 196,402, Wisconsin voted to repeal the Severson Act. Milwaukee residents supported this proposal by a vote of six to one. Locally socialist Mayor Daniel Hoan opposed prohibition, but he also felt that alcoholic consumption had to be limited. Rather than prohibition, Hoan suggested restricting the ability to purchase and distribute alcohol only to governments. He favored, for instance, a return to city-run beer gardens.[6] When prohibition came to an end in 1933, various celebrations took place in Milwaukee, including the Midsummer Festival at the lakefront, serving as the precursor to Summerfest.[7]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Richard C. Crepeau, “Prohibition in Milwaukee” (MA thesis, Marquette University, 1967), 18-19, 35, 65-66, 99, 107; Ashley Zampogna, “Canoli in the Cream City,” e-polis 3 (Fall/Winter 2009), 75-77.

- ^ Crepeau, “Prohibition in Milwaukee,” 20-21, 33.

- ^ Robert W. Wells, This Is Milwaukee (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970), 191-193.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 238.

- ^ Crepeau, “Prohibition in Milwaukee,” 27-28, 39, 91.

- ^ Jeffrey Lucker, “The Politics of Prohibition in Wisconsin, 1917-1933” (MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1968), 76-77, 80-87, 99-105, 113-117, 122-129.

- ^ “Milwaukee Timeline,” Milwaukee County Historical Society website, last accessed July 18, 2018.

For Further Reading

Crepeau, Richard C. “Prohibition in Milwaukee.” MA thesis, Marquette University, 1967.

Lucker, Jeffrey. “The Politics of Prohibition in Wisconsin, 1917-1933.” MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1968.

Rank, Kathryn Marie Gilbert. “Women and Prohibition in Milwaukee.” MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, 1978.

Wells, Robert W. This Is Milwaukee. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970.

Zampogna, Ashley. “Canoli in the Cream City.” e-polis 3 (Fall/Winter 2009): 60-83.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.