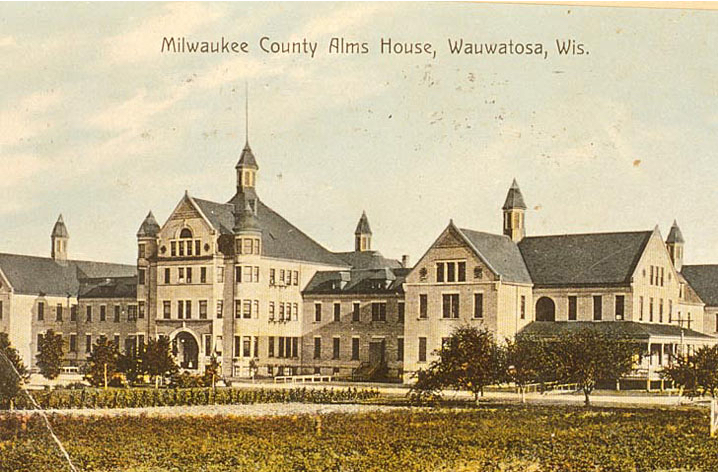

The Milwaukee County Institutions are a collection of programs, facilities, and complexes that have met a wide variety of county health and quality of life needs. Beginning in Milwaukee’s territorial phase (1835), the county’s care for the poor took the form of outdoor relief. Aid distribution was based on personal situation and overseen by two County-Board appointed Superintendents who reviewed applications for county aid.[1] As Wisconsin moved towards statehood in 1848, lawmakers designed legal codes that permitted local townships to care for the poor and tax citizens to fund relief programs. Section 49 of the Wisconsin Public Statutes decreed that city municipalities were responsible for the care of the poor, but a separate provision allowed supervisors of county boards to assume control if two-thirds of their members voted so.[2] Overlapping systems of authority were consolidated under the Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors, and as the city’s population and need for aid grew, these officials broke ground on a series of county aid facilities in Wauwatosa.[3] The County Poor Farm (or Almshouse opened in November 1852, providing aid and lodging to Milwaukee’s destitute. The home was quickly overwhelmed with the needy, as the facility became a proverbial dumping ground for paupers, orphans, the infirm, and the mentally disabled. The spread of disease, both in the city and in the Almshouse, spurred the county’s first hospital that opened in 1861, providing much-needed medical care for the county’s ill. After a fire in 1880 destroyed major portions of the complex, the County Board embraced the Public Health Movement to reorganize and rebuild social welfare facilities.[4] By the turn of the century, Milwaukee County Hospital offered unparalleled healthcare and professional training for doctors and nurses.[5]

With medical care facilities in place, county officials turned their attention to the next major social issue plaguing the city: mental illnesses and disability. Medical understanding of mental illness was still in an extremely primitive stage, as those deemed “insane” were often imprisoned, treated with painful treatments, or simply kept in isolation.[6] A series of investigations revealed the harrowing conditions that mentally ill patients faced in poorhouses, prisons, and almshouses. The County Board took action in 1880, building an insane asylum, but as Milwaukee grew rapidly at the turn of the twentieth century, these facilities were quickly overwhelmed with patients.[7] The rise of Progressivism fueled a complete overhaul of county services.[8] Several job training and home economics facilities expanded, allowing residents to learn agricultural techniques, along with practical skills such as sewing and weaving.[9] Medical care, however, remained the primary need of county residents, forcing County General to expand again in early 1930s.[10]

The economic chaos of the Great Depression in 1929 hit Milwaukee hard, and county facilities and programs were ill equipped to handle the increased demand for social services.[11] Long-time manager of county institutions, William L. Coffey, made skillful use of federal assistance through the Works Progress Administration, saving both the county complex and residents from frightful costs. Unemployed citizens were put to work renovating crumbling buildings, fixing county infrastructure, and creating green spaces for residents.[12] After World War II, the County Board formed the Department of Public Welfare; this separate agency was given the responsibility of care for the elderly, the blind, and dependent children, and placing orphans in foster homes. After Coffey retired from office in 1952, the next thirty years proved turbulent for county leadership as five directors of county institutions came and went.

On the heels of President Lyndon Johnson’s successful lobbying for Medicare and Medicaid expansions, the county took advantage of additional federal funding to build a regional medical center on the Wauwatosa grounds. The Marquette University School of Medicine, dealing with credential and financial woes, reorganized itself in favor of collaborating on a new institution, including a medical training hospital. Named after the wealthy donor Kurtis R. Froedtert, the Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital opened in 1980, shifting healthcare responsibilities between Froedtert and County General Hospital, now renamed the Milwaukee County Medical Complex. The budgetary cuts of the 1980s disrupted the county’s longstanding commitment to social welfare, as services were reduced at both the state and federal level. By the early 1990s, county officials sought to limit the county’s financial obligations by closing John L. Doyne County Hospital and outsourcing care to private clinics. The county-run hospital was purchased by Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital in 1995.[13] The agreement ensured that Froedtert would provide medical care to the county’s most needy residents, but it also shifted the responsibility of social services onto private providers across the region. The county would ultimately pay for some of these healthcare costs under the General Assistance Medical Program (GAMP) and Badgercare.[14] Today, the Milwaukee Regional Medical Center, located on the grounds of the county’s first social service facilities, features six partnering organizations: the BloodCenter of Wisconsin, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Curative Care Network, Froedtert Hospital, the Medical College of Wisconsin, and the Milwaukee County Behavioral Health Division.[15]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Steven Avella, “Health, Hospitals, and Welfare: Human Services in Milwaukee County,” in Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, ed. Ralph M. Aderman (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987), 197-198.

- ^ Avella, “Health, Hospitals, and Welfare,” 199.

- ^ Harry H. Anderson and Frederick I. Olson, Milwaukee: At the Gathering of Waters (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1981), 46-47.

- ^ Dennis Pajot, Building Milwaukee City Hall: The Political, Legal and Construction Battles (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2013), 164-165. Pajot explores Henry C. Koch’s involvement in facilitating the building of the Milwaukee County Insane Asylum and the struggles to get the facility approved by the County Board. See also Gail Dorothy Bremer, “The Wisconsin Idea and the Public Health Movement” (M.S. thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1963), 48-49.

- ^ Avella, “Health, Hospitals, and Welfare,” 205-206.

- ^ Thomas George Ebert, A Social History of the Asylum: Mental Illness and Its Treatment in the Late 19th and Early 20th Century (Bristol, IN: Wyndham Hall Press, 1999), 177-191.

- ^ “Milwaukee County Asylum,” Asylum Project, accessed February 10, 2015.

- ^ Avella, “Health, Hospitals, and Welfare,” 218-219.

- ^ Avella, “Health, Hospitals, and Welfare,” 221-223.

- ^Avella, “Health, Hospitals, and Welfare,” 228.

- ^ “The Depression Hits Milwaukee,” Milwaukee County Historical Society, accessed February 10, 2015.

- ^ Avella, “Health, Hospitals, and Welfare,” 231.

- ^ Larry Gage, “Why Do Public Teaching Hospitals Privatize?” in The Privatization of Healthcare Reform: Legal and Regulatory Perspectives, ed. M. Gregg Bloche (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 179-180.

- ^ Gage, “Why Do Public Teaching Hospitals Privatize?,” 179-180.

- ^ “Our Members,” The Milwaukee Regional Medical Center, accessed February 10, 2015.

For Further Reading

Avella, Steven. “Health, Hospitals, and Welfare: Human Services in Milwaukee County” in Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, ed. Ralph M. Aderman. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987.

Pajot, Dennis. Building Milwaukee City Hall: The Political, Legal and Construction Battles. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2013.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.