The integrated health care systems that currently dominate health care provision in Milwaukee were created in the last decade of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first. Before the many mergers and acquisitions that formed them, health care was provided by many small independent providers. In 1988, there were twenty distinctive community hospitals in the metropolitan area and myriad doctors’ offices, corner drug stores, visiting nurses, counselling centers, nursing homes, and other forms of health care providers.

Although this entry will address the array of health care services, hospitals receive disproportionate attention. While hospitals kept records and attracted scholarly attention, the very small providers of health services left little historical record—of their numbers, who they were, what they did, or who they served. They could hang out a shingle one day and take it down the next without much notice.

1848-1918: Home Care and Charity in Early Milwaukee

In 1846 when Milwaukee appeared on the map, most health care was provided in the home by family caregivers. These people purchased products they judged to be useful from itinerant peddlers, general stores, and occasionally a specialized store like the drug store in Milwaukee that advertised its stock of salts, leaves, flowers, barks, castor oil, and iodine in the Medical Times. Resources permitting, families might seek a consultation with a doctor or other provider.

Medical doctors were trained in proprietary medical schools, often of fleeting existence. These schools taught a variety of approaches, the adequacy of which was judged by their ability to enroll students rather than their effectiveness in training them as doctors. None of the schools of medicine (or pharmacology or dentistry) had the scientific knowledge of disease that could enable them to alter its course. Allopathy, the closest precursor of contemporary medicine, was the most popular approach in Milwaukee in the late nineteenth century. It was an aggressive approach that included bleeding, purging, drugging, injecting and cutting. Homeopathy was also popular in Milwaukee. A gentler, drug-based approach that originated in Germany, it came to Milwaukee with German immigrants. Other approaches with a significant presence in the city were Christian Scientists and Osteopaths.[1]

Midwives were defined not by professional training, but by their role in the birth setting. Many were older women within a family or social network who were experienced with childbirth. Some developed a broader clientele and considered themselves midwives in a more professional sense. Some obtained formal training, either as an apprentice to a practicing midwife or in midwifery schools, which became more common over time. According to Milwaukee Health Department data, in the years 1870-1920, nine hundred local women identified themselves as midwives.[2] Another source of health-care provision were barber-surgeons. As their name implies, they cut hair, pulled teeth and performed simple surgeries; the speed with which they operated was a cardinal attribute.

The ability of families and friends to be self-sufficient was severely stressed in the second half of the nineteenth century. Immigrants arriving in the city from different homelands brought disparate germs against which other arrivals lacked immunity. The deadly brew of germs that resulted led to repeated plagues of smallpox, diphtheria, typhus, tuberculosis, and cholera between 1845 and 1880. The plagues devastated support networks that were already truncated by immigration and made orphans of many children.[3]

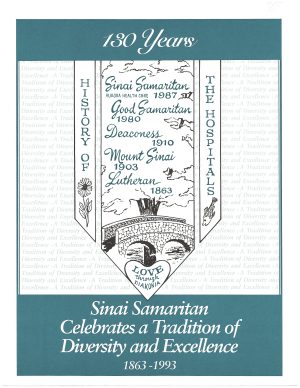

Organized religion was first to offer assistance to those without the capacity to provide home care. Seven of the first eleven “hospitals” in Milwaukee arose under religious auspices and under the leadership of a specific bishop, pastor, or rabbi. Four were Catholic (St. Mary’s, 1848; St. Joseph’s, 1883; St. Anthony’s, 1905; Misericordia, 1908); two were Lutheran (Milwaukee Lutheran, 1863; Deaconess, 1910); and one was Jewish (Mount Sinai, 1903).[4] Unlike hospitals today, these early institutions were not devoted to “medical” diagnoses. They admitted a vague population of individuals incapacitated by illness, disability, mental impairment, senility, and social isolation. The patients’ shared characteristics were lack of family members able or willing to care for them, as well as lack of money.

Hospital founders raised money from donors in their national and international religious networks. For “know-how” and labor, they turned to religious orders that had long operated hospitals in Europe.[5] Bishop John Martin Henni appealed to the Daughters of Charity (of French origin) to launch St. Mary’s Hospital (1848). In 1883 he recruited the Franciscan Sisters of Olpe, Germany, to open St. Joseph’s. Governments with responsibility for special populations were similarly dependent on nuns. The Daughters of Charity were recruited to care for prisoners in the jail, merchant seamen, and immigrants quarantined on Jones Island (1848-1854).[6] In the case of the first Protestant hospitals, founding pastors turned to the Deaconesses of Kaiserwerth, Germany. The first care provided by the Daughters and the Deaconesses was on foot, door to door.[7]

The building of physical structures for hospitals faced “not in my neighborhood” resistance as potential neighbors feared them as places of death—which indeed early hospitals often were. The Daughters of Charity found a location for St. Mary’s at North Point (near current-day North Avenue and Lake Drive); a neighborhood that is now affluent but was at the time the location of the Milwaukee County Poor Farm. The leadership of Milwaukee Lutheran located the hospital on farmland at the city’s then-western edge, at the corner of what is now Kilbourn and Twenty-second. The Lutherans were joined in this neighborhood by institutions created by other German groups, including the Jewish Mount Sinai and Deaconess, organized on the West Side by a breakaway group of conservative German ministers.[8]

Some early urban hospitals had missions to specific groups: St. Anthony’s (1905) started life as the infirmary of a Capuchin school for black children; Misericordia (1908) was a home for unwed mothers. Children’s Free Hospital flowed from the activism of wealthy East Side women concerned with the malnutrition of immigrant children. Before 1918, there were two exceptions to the pattern of hospitals being founded as charitable institutions: Malone Hospital (1903) and Columbia Hospital (1909). These were places of restorative care, although along quite different lines. Malone was a for-profit emergency hospital owned by Dr. William F. Malone, a surgeon who patched up victims of industrial accidents. The only hospital south of the Menomonee Valley, Malone was located in a house at Madison and Third Street with ungainly wings attached to accommodate patient beds. It was handy to the front door of the Allen-Bradley plant. Two name changes and several decades later, Malone, now St. Luke’s, acquired a reputation for pioneering heart surgery. It was the site of an early heart transplantation (Dr. Derward Lepley, 1968) and the landmark coronary artery bypass operation of Dr. Dudley Johnson (1968) that opened coronary artery bypass surgery to wide application.[9]

Columbia’s goal was to base care in scientific medicine, which was newly achieving a place in medical practice. Columbia’s founding was led by a group of elite doctors who were products of Eastern medical schools that were teaching the scientific approach to health care. In this model, the ideal hospital was a place where practice was attentive to scientific knowledge and supported laboratories to validate treatments and to strengthen the scientific base. For funds and a board, the Columbia doctors partnered with leading citizens attracted to the cause.[10]

1919-1945: Foundations of Scientific Medicine

The arrival of scientific medicine in the United States, represented by the founding of Columbia Hospital, is usually assigned the date 1910, when the Carnegie Foundation published a devastating critique of American medical education. It was named for its author, Abraham Flexner, who evaluated medical schools, scoring their capability to deliver a scientific curriculum. The bar for passage was high, requiring, for example, the availability of expensive laboratories in physiology, chemistry, and microbiology. Many schools were recommended for closure, including both of the two then functioning in Milwaukee.

The report was influential with state licensure boards that proceeded to make a medical license dependent on graduation from an accredited medical school; however, it would be years before the science-trained graduates replaced their diverse forbearers. The slow accretion of new doctors was only part of the problem. Science in the early twentieth century could show few clinical results. It is worth remembering that nearly a decade after Flexner, doctors had no tools to stay the deaths of fifty million victims of the worldwide influenza pandemic in 1919.[11]

Scientific successes came more quickly in surgery and public health. By 1925, surgeons were seeing the positive results of sterile operating theaters on patient survival and were embracing the hospitals as preferable to the home as sites for surgery.[12] To assure that all hospitals adhered to sterile practice, the newly-organized American College of Surgeons (ACS) launched a “Standards movement” (1919). The campaign languished, however, as hospitals resisted inspection until the surgeons found an ally in Father Charles Moulinier. A regent of the Marquette School of Medicine in Milwaukee and organizer of the Catholic Hospital Association, Moulinier broke the logjam when he pledged the participation of 600 Catholic hospitals[13]

The controversy surrounding successful control of germs in Milwaukee in the 1920s has been well-documented. For its accomplishments in garbage collection, pasteurization of milk, and quarantine, the American Public Health Association repeatedly named Milwaukee the “Healthiest City.” Milwaukee also succeeded in keeping the death rate from influenza low compared to most other cities. Under Socialist Mayor Daniel Hoan, the Commissioner of Health engaged medical professionals across the city in public education during the influenza outbreak and courageously prohibited all public gatherings—including schools, theaters, saloons, and churches![14]

Within the medical community, the emphasis on specialization that accompanied the advance of science produced a backlash. In 1944, two osteopathic hospitals (Lakeview and Northwest General) incorporated with charters declaring their opposition to excessive specialization and reliance on technology. In 1949, Doctors Hospital was incorporated for family medicine. In nursing, the increasing emphasis on academic versus practical education was an area of great controversy. Since the founding of the first hospitals by nuns, generations of nurses had trained in residential programs at hospitals. In this system, trainees lived at the hospital and adhered to strict hours and behavioral rules similar to those of a convent. It was many decades before differences of opinion were resolved in favor of academic qualifications. The hospital-based residential programs continued operation in Milwaukee until 1962 at St. Mary’s, until 1973 at Milwaukee Lutheran, until 1974 at Mount Sinai, and until 1986 at Deaconess. Columbia College of Nursing celebrated its centennial in 2001, albeit now with university partners.

1946-2010: Health Care for the Middle Class

The interwar years saw the Flexner-trained doctors come of age, specialization and professional organization, and changed public perception of hospitals. Penicillin after the war changed the doctor from someone who could explain disease to someone who could end it. Resources expanded exponentially. A wartime wage freeze introduced widespread employer-provided hospital insurance and the federal government massively invested in medical science, medical schools, and hospitals. What was charity in 1945 was big business in 1975. Decisions that, before the war, had been based on local factors and priorities, increasingly were shaped by federal policies and funding programs.

Perhaps the most important was the federal Hill Burton Survey and Construction Act (1946). The movement of veterans and others to outlying neighborhoods and suburbs after the war sparked the expansion of hospital systems in the area. These hospitals were conceived as middle-class entities serving local health-insured residents—a hospital of fifty beds and an emergency room for “our town.” Matching funds were raised at church card parties and bake sales, penny drives at schools, by Girl Scouts canvassing door to door and, most important, through partnerships with local government to provide the federal cost-share. A local hospital was not only a convenience but a mark of community pride.

On Milwaukee’s South Side, Hill Burton funds enabled the construction of St. Francis Hospital (1956) and Trinity Memorial (1958), which served the suburbs of St. Francis, Cudahy, and South Milwaukee. It also enabled a building program at St Luke’s (formerly Malone) at a new site on Oklahoma Ave. (1952) and at West Allis (1961), as well as the construction of Community Memorial Hospital of Menomonee Falls (1964) and a reconstruction of Misericordia Hospital in Brookfield, renamed Elmbrook Memorial (1969).

Mental Health Care and Community Clinics

The postwar decades saw huge improvements in the care of the mentally ill and the elderly—both chronically underserved populations. The long national campaign to end the incarceration of mental patients in large state hospitals achieved passage of the Community Mental Health Act of 1963. In 1965, with passage of Medicare, the elderly were added to the ranks of the insured.[15]

Wisconsin’s leadership in programs of public health and health planning was also seen in mental health care. Milwaukee was thrust into the spotlight by a court ruling that dramatically altered the requirement for commitment for institutional care. In Lessard v. Schmidt (1972), a Milwaukee federal district judge agreed with Milwaukee Legal Services that it was unconstitutional for individuals to be committed to mental institutions against their will except with demonstration that they were a danger to themselves or others. This was a much higher bar than the previous need to show patient benefit, which generally required only the recommendation of a doctor.

By this time, however, Wisconsin had been, for many decades, devolving services to local (county) governments. By the time of the Community Mental Health Act of 1963, the national ethos of social amelioration grant programs now favored not only neighborhood locations but nongovernmental, non-hospital sponsorship, and non-medical administrative leadership (e.g. psychologists and social workers). With considerable commitment to the rejected models (government-sponsored, hospital-based, and M.D.-led), Milwaukee strained to qualify for many of these grants. Local officials in Milwaukee (and elsewhere) were critical of federal interventions that bypassed established channels, which they said produced entities that were incompatible with local policies, resource allocations, and long-term plans. In addition, the construction grants for community mental health centers expired in eight years, leaving the state and local levels to pick up costs. Milwaukee also did not benefit from federal funding for neighborhood health centers, but other groups did establish neighborhood services, including Sixteenth Street and the Gerald L. Ignace Indian Health Center, Inc.

In 1978, the influential Robert Wood Johnson Foundation awarded large grants to five cities to demonstrate the capability of centralized urban health service providers, especially inner cities. The City of Milwaukee (the provider of public health services) in collaboration with Milwaukee County (the provider of hospital care) was awarded one of these grants. A common result of the case studies in the five cities was, unfortunately, to document the difficulty of changing the inherited fragmentation of hospital and primary care provision to underserved urban populations.[16]

Marketplace for Health Care

In 1981, President Ronald Reagan’s administration moved quickly to create a dramatically different environment for health services than that of the 1960s and 1970s. Attempts to establish prices for health care services had arrived a bit earlier with the introduction of Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs). More dramatic change arrived later when Medicare and Medicaid, and then private insurance companies, shifted to market-based purchase of services for large groups of people—vastly improving their leverage over providers. (A quirk of history is that until this time insurance companies and employers that provided insurance for employees, had accepted “cost-plus” payment inherited from the charity era.)

The result of market dynamics was rapid consolidation of health services providers. Beginning in 1988, smaller and financially weaker hospitals closed or were brought under the control of organizations with more profitable services and greater market share. These larger organizations, then, proceeded to absorb the even smaller formerly independent doctors’ practices, clinics, pharmacies, hospitals, visiting nurses, home care, assisted living, nursing homes, and hospices. The result was the four systems that exist in Milwaukee in 2018. The “invisible hand of the market” was promoted as a means to avoid the controversies that plagued programs that employed regulation and citizen participation. To a considerable extent, the change did create the impression that service cuts were made by market dynamics rather than by people.[17]

The health “systems” that successfully achieved sufficient scale to survive (and to exist into the twenty-first century) are Wheaton Franciscans, Aurora, Columbia St. Mary’s, and ProHealth Care. Wheaton and Columbia St. Mary’s have recently been acquired by Ascension Healthcare.[18] These provide services well beyond the service areas of the “flagship hospitals” around which they formed. In them, decisions driven by goals of market share and market success have replaced priorities of religious groups and communities. Milwaukee history is, however, embodied in consolidation that occurred between 1988 and 2010. Catholic-governed Wheaton Franciscan Health Care absorbed most Catholic institutions around its flagship hospital, St. Joseph’s. Aurora (flagship: St Luke’s) absorbed the dense group of non-Catholic hospitals of the Near West Side and South Side hospitals Trinity and West Allis (also non-Catholic), Hill-Burton hospitals, and a large number of formerly free-standing health services such as the Visiting Nurse Association of Milwaukee. ProHealth Care (flagship: ProHealth Waukesha Memorial) absorbed its regional neighbors, Oconomowoc Memorial Hospital (now ProHealth Oconomowoc Memorial Hospital) and Elmbrook Hospitals (which was later absorbed by Ascension).[19] In 1995, Froedtert Hospital opened as a full-service teaching hospital on the grounds of the old County hospital, which finally closed. Froedtert Health system acquired Community Hospital of Menomonee Falls and hospitals of some outlying communities. Columbia and St. Mary’s had the most difficult time surrendering their historic identities, finally choosing each other for a strong East Side presence under the auspices of Ascension.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Elizabeth Barnaby Keeney, Susan Erich Lederer, Edmond P. Minihan. “Sectarians and Scientists: Alternatives to Orthodox Medicine,” in Wisconsin Medicine: Historical Perspectives, ed. Roland Numbers and Judith Walzer Leavitt, (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981), 49. This entry was first published on June 3, 2019 and revised on June 7, 2019.

- ^ Kala R. Kluender, “With Wisconsin Women: Midwives in the Badger State, Late 1800s to 2007,” April 23-30, 2007, University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Ebling Library, accessed April 10, 2018.

- ^ Ellen D. Langill. A Tradition of Caring: The History of Milwaukee’s Three Primary Service Hospitals: Lutheran, Mount Sinai, and Evangelical Deaconess (Milwaukee: Sinai-Samaritan Hospitals History Committee, 1999).

- ^ Langill. A Tradition of Caring.

- ^ Brenda W. Quinn and Ellen D Langill, Caring for Milwaukee: The Daughters of Charity at St. Mary’s Hospital (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Publishing Group, 1998).

- ^ Langill, A Tradition of Caring.

- ^ Langill. A Tradition of Caring, 11, 55-57.

- ^ “Milwaukee’s Hospitals,” Milwaukee Medical Times (Milwaukee: Medical Society of Milwaukee, 1947), 61.

- ^ Ellen D. Langill, The Columbia Way: Columbia Hospital, 100 Years of Excellence 1909-2009 (Milwaukee: Columbia Hospital, 2010).

- ^ “1918 Pandemic,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, accessed April 29, 2019.

- ^ Joel Howell, Technology in the Hospital: Transforming Patient Care in the Early Twentieth Century (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 341.

- ^ Rosemary Stevens, In Sickness and in Wealth: American Hospitals in the Twentieth Century (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1989), 384.

- ^ Judith Walzer Leavitt. The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982), 231-239.

- ^ Bruce Murphy and John Pawasarat, “The Rise of a Mega-Hospital: The Politics behind the Building of a High-Tech, High-Cost Medical Center,” in Health Services Management: Readings and Commentary, 4th ed., ed. Antony Kovner and Duncan Neuhauser (Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press, 1990).

- ^ Ann Lennarson Greer, Scott Greer, and Tom Anderson, “The City’s Weakest Dependents: The Mentally Ill and the Elderly,” in Cities and Sickness: Health Care in Urban America, ed. Ann Lennarson Greer and Scott Greer (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1983), 139-178; Scott Greer and Ann Lennarson Greer, “The Continuity of Moral Reform: Community Mental Health Centers,” Social Science and Medicine 19, no. 4 (1984): 397-404.

- ^ Edith M. Davis and Michael L. Millman, Health Care for the Urban Poor: Directions for Policy (Towota, NJ: Rowman and Allanheld, 1983); Eli Ginzberg, Edith M. Davis, and Miriam Ostow Local Health Policy in Action: The Municipal Health Services Program (Towata, NJ: Rowman and Allanheld, 1985).

- ^ “Ascension SE Wisconsin Hospital—Elmbrook Campus,” Ascension website, accessed May 3, 2019.

For Further Reading

Howell, Joel. Technology in the Hospital: Transforming Patient Care in the Early Twentieth Century. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Langill, Ellen D. A Tradition of Caring: The History of Milwaukee’s Three Primary Service Hospitals: Lutheran, Mount Sinai, and Evangelical Deaconess. Milwaukee: Sinai-Samaritan Hospitals History Committee, 1999.

Leavitt, Judith Walzer. The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982.

Numbers, Roland, and Judith Walzer Leavitt, eds. Wisconsin Medicine: Historical Perspectives, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 1981.

Stevens, Rosemary. In Sickness and in Wealth: American Hospitals in the Twentieth Century. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1989.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.