Throughout its history Milwaukee has seen shifting and complex interplays among local, state, and federal government policies regarding support provided to needy families through work relief and financial aid welfare payments. Three periods in the last century highlight competing theories about work relief and welfare support that operated in Milwaukee. In the Great Depression years of 1930 to 1933, the City and County responded with local funding for short-term work relief along with financial and commodities aid to families. From 1933 to 1941, the federal government committed large-scale infrastructure work projects. In the 1990s and 2000s, the state government reduced both work relief and welfare aid.[1]

The first poor relief laws passed in the State of Wisconsin in 1849 placed responsibility for care of the indigent on local governments, with family members expected to provide support for relatives whenever possible. The term “indoor relief” refers to aid to the poor provided in shelters and institutes. In Milwaukee, as elsewhere in Wisconsin and the US, indoor relief developed in the form of county poorhouses, mainly for the elderly, and orphanages for abandoned and destitute children, with older children sometimes “bound out” in work programs as apprentices. Indoor relief contrasted with “outdoor relief,” which involved distribution of items such as foodstuffs, winter clothing, and coal. In 1913 the state legislature passed a Mother’s Pension Act (renamed Aid to Dependent Children in 1927) that allowed impoverished mothers to petition the courts for aid grants for their children. As of 1930, nearly all (98 percent) of the funds for the ADC program were provided by county governments.[2]

A bulletin issued by the Wisconsin Industrial Commission in 1932 defined three competing theories underlying relationships between work relief and welfare payment programs. The first theory holds that needy individuals should be made to work before receiving direct aid. Under this approach, work is used primarily as a screening device for determining whether individuals and families “deserve” relief. The second theory maintains that if money is given for relief, the community should receive a benefit in return. Instead of just offering welfare cash assistance, the government finances work to ensure that the community receives tangible benefits for its payments. The third theory posits that work should be provided in order to preserve the morale and self-respect of those given work. This approach expects the work to be of sufficient value that both the worker and the community benefit in a significant way.[3]

After the Great Depression hit Milwaukee in the 1930s, City and County officials responded immediately with programs to increase public employment opportunities for local residents (“work relief”) as well as to provide direct financial or other tangible assistance (“welfare”) to families in need. Whenever financially possible, Milwaukee embraced the third approach to work relief. At no time was work mandatory during the Depression in Milwaukee County. Cash and commodities assistance was made available based on family need, with work optional.

Local relief and welfare aid programs were developed as part of a larger community-wide response to massive unemployment. First, Milwaukee’s Socialist mayor Daniel W. Hoan acted to retain as many City employees as possible by instituting a ten percent monthly pay cut for all City employees, with a corresponding ten percent reduction in working time. Some City departments used shortened workdays, while others placed their workers (particularly road workers, laborers, and civil engineers) on month-long furloughs without pay. Even as elected officials cut their own pay and that of City workers, the City invested $600,000 in property tax funds for work relief projects in the winter of 1930-31, with workers selected based on the urgency of their financial need and family size. Men were offered one ten-day shift of work (and a possible second ten-day shift if they had large families) in street sanitation, ash collection, grading of land for new playgrounds, extending the underground conduit system for fire and police alarm cables, park projects, and painting of election booths and Milwaukee Public Museum space. Hoan later reflected with pride that Milwaukee was the first large community to provide work for residents on relief on a voluntary basis and to pay cash for the work.[4] In 1931 the City employed 11,000 men in short-shift projects; a year later, 20,500 were employed. To promote private sector job opportunities for residents, the City established an employment office in the basement of City Hall and distributed work order forms through the local dairy routes to encourage households to hire residents for temporary odd jobs.

The Milwaukee County government similarly began work relief projects through its Department of Outdoor Relief, which paid fifty cents an hour for unskilled labor and the union minimum wage rate for skilled labor. Workers’ hours were established based on each needy family’s “budget” as set by the Department. The early projects included work in the parks grading picnic and athletic areas, constructing trails and walks through wooded areas, constructing lagoons, installing drainage systems, and thinning underbrush. Workers were paid cash wages, and the County encouraged local grocers and the utility companies to provide discounts to the relief workers. By 1933 Milwaukee found it necessary to use its ten percent pay fund for general City operating costs and to further reduce the number of City employees on rotating work and part-time schedules.

Nationally, as the Depression wore on, it became evident that municipal and county governments could not handle the immense expenses of relief and unemployment in their communities. Even with reductions in public services, a growing number of localities faced bankruptcy. At the time the federal government aggressively entered the business of relief payments and job creation in 1933, at least thirteen million American workers, or about a quarter of the total labor force, were estimated to be unemployed. The Franklin D. Roosevelt administration assumed federal responsibility for large-scale employment programs for workers on relief, and Milwaukee quickly developed sweeping proposals in response.

When federal funds were made available under the Civil Works Administration (CWA), Milwaukee City and County officials spent only three weeks planning. They developed projects to employ 26,000 workers in the winter of 1933-34 doing landscaping, road grading, street repair, and painting. One of the largest of the City’s 138 CWA projects employed almost 2,000 men straightening an S-curve on the Milwaukee River and building a lagoon and islands in Lincoln Park. The County also used the CWA to build swimming pools at Greenfield and McGovern Parks.

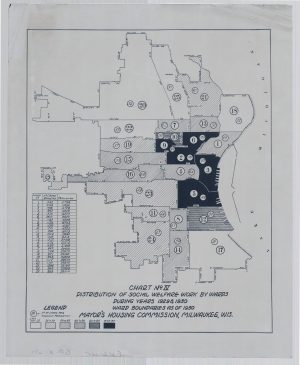

Under the CWA the federal government provided 100 percent of wages and up to 25 percent of the cost of materials. The CWA work paid prevailing and union minimum wage rates for skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled labor. Nearly all (98 percent) of the workers employed by the CWA in Milwaukee County were males. About 40 percent came from the public relief rolls while 60 percent were referrals from the public employment office. Only 2.4 percent were African Americans, who then comprised less than 2 percent of the county’s population.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), which replaced the CWA, offered a contrasting model for wage and eligibility standards. The FERA regulations allowed work relief only for persons on county relief and required local welfare agencies to determine each family’s income needs and resources based on home visits and testimony regarding the families’ rent and other expenses. County relief department “visitors” made calls to client homes, confirmed their living situation and family expenses, certified eligibility for one employable household member (almost always the male parent), and determined the level of family need (“budgetary deficiency”). Annual reports of the County relief department suggest a highly intrusive role for these “visitors,” with an emphasis on defects of clients, “symptom of problems,” and “uncovering” potential work skills unrecognized by the needy clients.[5]

In 1935 the President and Congress adopted a new set of work and relief programs that provided limited support to local governments for “unemployable” populations while assuming federal responsibility for large-scale employment programs for workers on relief. These initiatives represented a three-pronged attack on the problems of unemployment and local relief needs. First, federal aid was provided under the Social Security Act of 1935 for persons deemed “unemployable”—the needy aged, mothers with dependent children, and blind persons. Secondly, the Public Works Administration (PWA) was expected to improve the economy through support for large-scale federal, state, and local public works projects employing skilled workers. Finally, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was designed to provide immediate work for able-bodied persons from the local relief rolls.

“Because of its focus on providing work for families and individuals supported by municipal and county relief agencies, WPA regulations required that ninety percent of project workers (and later ninety-five percent) be on public relief or certified for public relief.”[6] Under WPA regulations only one person in a family (usually the male parent) could have a WPA job. Beginning in December of 1935, County relief funds and commodities (food, milk, fuel, clothing, etc.) were provided to families of WPA workers whose pay did not meet the minimum required.

Milwaukee’s early WPA projects for 12,000 workers moved well beyond “fix-up” and “clean-up” work to long-term infrastructure commitments, including constructing and improving city streets, sewer and water mains, city playgrounds, and public buildings. City and County departments identified public works projects which could have long term benefits for the community. Foremost in utilization of work relief programs was the Milwaukee County Parks Commission, which used the WPA to build one of the finest park systems in the country, constructing swimming pools, pavilions, bathhouses, administration and service buildings, new roads, sewers, drainage lines, lagoons, lighting systems, and recreation areas. By spring of 1940, WPA workers in Milwaukee had constructed 84 public buildings, 884 miles of streets and highways, 31 bridges and viaducts, 206 miles of sidewalks, 187 miles of curbs, and 215 miles of street lighting. They also reconstructed 478 buildings.[7]

Many of the non-construction WPA projects in Milwaukee were quite innovative. The Public Museum sponsored the work of men and women who built exhibits and classified specimens and collections, first for the Milwaukee museum and then for other museums around the state. The health department employed workers to assist in citywide immunization of children for diphtheria, smallpox, and scarlet fever, as well as to sew needed medical materials. The school board used workers to offer recreational and adult education activities, and the Park Commission used workers to design and sew costumes for summer operas. The City created jobs for over six hundred “white collar” workers modernizing city property assessment, tax, legal, engineering, and school board records, surveying all privately owned properties for tax assessment purposes, conducting a fire prevention survey of all buildings in the city, and cleaning and indexing library materials.

In August 1935 the County began offering WPA work for the several thousand women classified as their family’s “breadwinner.” Women working in shifts of three to four hundred operated a sewing center, which made nearly a million articles of clothing for needy families and children in the community. Under sponsorship of Milwaukee State Teachers College, another manufacturing operation (the Milwaukee Handicraft Project) evolved, ultimately employing over 5,000 workers, mostly women, making educational toys, dolls, wall hangings, furniture, rugs, and textiles for use by public schools, hospitals, orphanages, nurseries, and universities.[8] The expectation that single mothers qualifying for Aid to Dependent Children should be at home was reinforced by the Roosevelt Administration in March 1937 when according to the Milwaukee Journal several hundred mothers with young children were forced off of WPA work projects and told to apply for ADC cash assistance if they needed financial help.[9] At the end of 1937, Milwaukee County reported that 2,035 families were receiving Aid to Dependent Children, out of 44,200 cases on work relief and direct welfare assistance.[10]

With the advent of World War Two, the nature of work relief projects in Milwaukee County shifted as the WPA was phased out and the economy dramatically improved. County-operated work programs initiated in 1941 emphasized maintenance and operation of county services—work activities not permitted under the WPA. In the 1950s County relief offered sheltered workshop activities for individuals with disabilities as well as service jobs maintaining county parks, buildings, and institutions for the unemployed. During the 1960s federal job training dollars were increasingly focused on the parents receiving AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) support, and away from the County’s general assistance and a largely male, single population. During the following decade, the federal government introduced a Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) as a counter-cyclical program to stimulate local economies, thereby allowing skilled as well as unskilled workers to engage in projects initiated by local governments and non-profit agencies. Meanwhile, state and federal welfare policies continued efforts to move parents receiving AFDC into private sector employment.

The 1930s era of relief and welfare was a distant memory decades later in the mid-1990s when Wisconsin Republican Governor Tommy Thompson and the state legislature introduced dramatic changes in welfare and relief policies. In 1995 unemployed and “working poor” adults were residentially concentrated by race in central city neighborhoods of Milwaukee. At the same moment, the unemployment rate in the four-county Milwaukee metropolitan area was a very low 3.6 percent. Metro area employers reported that over half of their job openings were “difficult to fill.”[11] The racial/ethnic demographics of the population in need had dramatically changed. While the work relief population in Milwaukee in 1937 was 93 percent white and 85 percent male, under Thompson’s proposals the Milwaukee County AFDC population expected to find work and leave aid was 87 percent minority (i.e., non-white and non-Hispanic) and 91 percent female.[12]

Public policies enacted to reduce welfare aid rolls in Milwaukee County in the 1990s came in two phases. Of about 36,000 Milwaukee County families receiving AFDC in 1995, about 9,000 families were moved into two categories of children deemed eligible for cash assistance: Kinship Care for children in the care of non-legally responsible relatives (e.g., aunts, grandparents, etc.) and Caretaker Supplement benefits for children in families headed by a parent certified by the Social Security Administration as needy and unable to work due to a disability (i.e., receiving SSI or SSDI, Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance payments). The remaining 25,000 families in the county receiving AFDC were subject to the new work activity and time requirements.

In the first phase of welfare caseload reductions from 1996 to 1997, Wisconsin cut the level of AFDC payments by six percent (lowering benefits and eligibility for employed families) and required mothers of children over three months of age to engage in up to forty hours of employment-preparation activities each week as a condition for receipt of cash assistance. Stricter enforcement of job search and employment-related program activities for up to forty hours a week led many employed families (who had been using partial AFDC payments to supplement their low wage earnings) to leave the AFDC program completely. Parents previously sanctioned with partial AFDC aid reductions for missing assigned activity hours or reporting requirements lost their aid for the entire family. Finally, single mothers were required to participate in heightened child support collection efforts.[13] Under these new state requirements, by the end of 1997 the number of number of Milwaukee County AFDC cases receiving aid and expected to find employment had dropped from 25,100 to under 4,100.

In the second phase of AFDC changes, beginning in fall of 1998, Milwaukee County families remaining on public assistance were subject to a time-limited state program labeled “Wisconsin Works” (or, as it is commonly known, “W-2”). Rather than base aid payments (using federal AFDC and its replacement, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) on family size, flat monthly payments (if allowed) were established based on tiers of work-type activities. Mothers caring for a newborn under twelve weeks of age were allowed a flat monthly payment of $673 (regardless of the number of other children in the family). Mothers lacking basic work skills could be placed in community service jobs (usually coupled with other employment-related activities) and were also given $673 a month payments. If they missed hours of work or other assigned activities, they could be docked a portion of their payment. Those parents with more serious barriers to employment could be assigned to “W-2 Transition” activities and were given $628 monthly income. Again, failure to participate in required activities would result in a lowered monthly payment. Mothers deemed “ready to work” based on recent or current employment history or an assessment of their potential job skills could be denied aid with or without employment advisory services.

Reminiscent of the county relief “visitor” of the 1930s, a “Financial and Employment Planner” (FEP) was authorized under W-2 to assess each needy family’s application for assistance. The FEP made an assessment as to whether the parent applicant or current aid recipient was “job ready” (and therefore denied welfare aid and services) or was in need of community service work or employment-related activities. Much of the TANF funding was used to support child care subsidies for families with steady but low-paying employment (whether in the W-2 program or not) in which another family or a child care center was paid to care for the children while the mother was at work. A review by the Wisconsin Council on Children and Families of TANF and federal child care benefits targeted to Milwaukee County families in the early 2000s found that over a third of the federal funds were dedicated to paying for child care for employed families with lower incomes and thirty percent of the funds went to cash assistance to needy families (including those in Kinship Care and Caretaker Supplement programs). Meanwhile 29 percent of the funds went to the vendors administering the W-2 program for their administration and service costs and profits.[14]

The W-2 programs in Milwaukee County are administered by non-government vendors who receive block grants for their work, coupled with incentives for getting families off aid. The state Department of Workforce Development reported that nearly half (48 percent) of the families receiving W-2 aid or services in 2002 (and off support in 2003) had zero earnings in the three-month quarter studied (October through December of 2003). Only 27 percent showed wage earnings above the federal poverty level.[15] The American Community Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that as of 2015 over 73,500 children in Milwaukee County were living in poverty.[16] To the extent that welfare and relief can alleviate this life condition, present programs are clearly falling short.

Unlike in the 1930s when Milwaukee City and County government had significant input into the operations of both welfare and government work relief efforts, the current W-2 program is a state-driven system with federal oversight but no opportunity for local government involvement. The work programs established by Milwaukee City and County governments in the 1930s supported the use of work relief to aid families while improving the morale and dignity of unemployed adults rather than as exercises to identify the poor “deserving” of aid for themselves and their children. Much of the government work performed during the Great Depression remains visible and valued to this day. The long-term legacy of the state’s “Wisconsin Works” program, at least as measured by state reports on family earnings and U.S. Census estimates of continuing family poverty, appears likely far less positive.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ The scholarly details addressing relief and welfare policies during the 1930s and 1940s throughout this essay are drawn from Lois M. Quinn, John Pawasarat and Laura Serebin, Jobs for Workers on Relief in Milwaukee County, 1930-1994 (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Employment and Training Institute, 1995).

- ^ Wisconsin Public Welfare Department, General Relief in Wisconsin: 1848-1935 (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Public Welfare Department, 1939).

- ^, Standards of Work Relief and Direct Relief in Wisconsin (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Industrial Commission, 1932).

- ^ Daniel W. Hoan, City Government: The Record of the Milwaukee Experiment (New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1936), 323-324.

- ^ Benjamin Glasberg, “Annual Report” (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Department of Outdoor Relief, 1935).

- ^ Lois M. Quinn, John Pawasarat, and Laura Serebin, Jobs for Workers on Relief in Milwaukee County, 1930-1994 (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Employment and Training Institute, 1995).

- ^ Quinn, Pawasarat, and Serebin, Jobs for Workers on Relief in Milwaukee County.

- ^ Mary Kellogg Rice, Useful Work for Unskilled Women: A Unique Milwaukee WPA Project (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 2003).

- ^ Robert M. Levin, “WPA Purges Rolls: Chiselers Found,” Milwaukee Journal, March 14, 1937.

- ^ Milwaukee Department of Outdoor Relief, Monthly Report, December 1939.

- ^ John Pawasarat and Lois M. Quinn, Survey of Job Openings in the Milwaukee Metropolitan Area: Week of May 22, 1995 (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Employment and Training Institute, 1995).

- ^ John Pawasarat and Lois M. Quinn, Demographics of Milwaukee County Populations Expected to Work under Proposed Welfare Initiatives (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Employment and Training Institute, 1995).

- ^ John Pawasarat, Financial Impact of W-2 and Related Welfare Reform Initiatives on Milwaukee County AFDC Cases (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Employment and Training Institute, April 1996); John Pawasarat, Analysis of Food Stamps and Medical Assistance Caseload Reductions in Milwaukee County: 1995-1999 (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Employment and Training Institute, January 2000); Kristin S. Seefeldt et al., Income Support and Social Services for Low-Income People in Wisconsin (Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute, 1998).

- ^ Jon Peacock, The Allocation of TANF and Child Care Funding in Wisconsin (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Council on Children and Families, 2006).

- ^ Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development, “Wisconsin Works Chartbook: Program Overview 1998-2003” (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development Division of Workforce Solutions Bureau of Workforce Information, 2006).

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau, 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.

For Further Reading

Hoan, Daniel W. City Government: The Record of the Milwaukee Experiment. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1936.

Peacock, Jon. The Allocation of TANF and Child Care Funding in Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Council on Children and Families, 2006.

Quinn, Lois M., John Pawasarat, and Laura Serebin. Jobs for Workers on Relief in Milwaukee County, 1930-1994. Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Employment and Training Institute, 1995.

Rice, Mary Kellogg. Useful Work for Unskilled Women: A Unique Milwaukee WPA Project. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 2003.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.