The World Health Organization defines sexual health as “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality” and emphasizes “it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity.”[1] In the context of Milwaukee’s history, the main focus of policies and practices surrounding sexual health, however, concerns the prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and touches the related topics of medicine, policing, and sexuality. The history of sexual health in Milwaukee is also a troublesome topic as very little record of it exists prior to the 1910s, before city and county officials made the matter an area of civic concern.

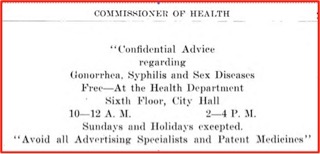

The transition of sexual health being considered a largely private medical issue to something in which local government need involve itself occurred both during a time of pending national emergency and one that saw Milwaukee’s public health infrastructure beginning to modernize.[2] In 1915, the city started a testing program for syphilis and gonorrhea—referred to at the time as venereal disease (VD)—through the Health Department.[3] According to the 1916 Health Department annual report, the program revealed that an alarming number of men—women were evidently not offered city testing until later—had been going to “quack” physicians or attempting to treat themselves.[4] Men testing positive for VD were referred to reputable doctors for treatment. If they were unable to afford such treatment, they were referred to the Marquette University medical clinic or the County Hospital.[5]

The entry of the United States into the First World War made Milwaukee’s VD fight a matter of national security. At the urging of the armed forces, the Wisconsin Society for Social Hygiene was formed, and an education program stressing “morality” as a means of fighting VD was offered locally. An accompanying law enforcement crack-down on vice was spearheaded by local law enforcement. [6] The wartime drive was decidedly focused on protecting young men. A secret program was instituted in the city by local and military police that required all women arrested on disorderly conduct charges to take a VD test. Women testing positive were detained until properly treated. This program was continued until the war ended.[7]

In the late 1930s, the city expanded its VD treatment programs, opening a “night clinic” in the office of the health department at City Hall. One night per week, the clinic catered to people who worked during the day.[8] The clinic at the county hospital expanded its staff and adopted new treatment methods for both men and women.[9] In 1940 the city undertook a massive testing program for syphilis, opening a clinic in the Plankinton Arcade and recruiting patients outside of factories and mills.[10] By 1941, the testing program had tested nearly 47,000 local residents and referred those testing positive to doctors for treatment.[11]

The Second World War again brought a sense of urgency to the city’s treatment of sexual health matters. As during the First World War, time lost by young men to the treatment of VD was time taken from the war effort. The crusade framed women as the culprits in the spread of VD. Local law enforcement agencies targeted both prostitutes and the so-called “v-girls” who sought out men in uniform for sex. City health commissioner E.R. Krumbiegel stated publicly that “promiscuous young women” were more to blame for the spread of VD among servicemen than prostitutes and urged police to take action against Milwaukee hotels, taverns, and dancehalls that had become known as “pick-up” hotspots.[12]

Following the war, city officials reported a spike in VD cases but maintained that Milwaukee’s infection rates were lower than most major cities.[13] The city opened a “social hygiene clinic” on North Water Street, that both diagnosed VD and treated its symptoms. VD checks were also performed on incoming prisoners at the county jail. Education was also cited as a main component of the fight for sexual health, but these programs continued to focus on “good character” and “morality” in lieu of what we would today call “safe sex” methods.[14]

During this time, sexual health care options for women in Milwaukee were growing. In 1949, the Maternal Health Center—which was founded in Milwaukee in 1935—expanded its services and became Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin. Planned Parenthood offered sexual health services to women who could not afford them and sexual education before it was readily available in schools. Initially offering their services only to married women, the clinic expanded its programs to all women in 1965.[15]

By the 1970s, the existing means of providing sexual health care were proving inadequate to handle the increasing need for treatment. In 1975, the Health Department venereal disease clinic in the Municipal Building on North Broadway had to remodel its waiting room to accommodate the rush of patients.[16] Both Milwaukee and Waukesha counties opened telephone hotlines to assist people seeking information and referrals.[17]

While Health Department officials blamed the increase in cases on youthful promiscuity,[18] others in the community took a more nuanced approach to sexual health. In 1974, citing a lack of “sensitive, accessible resources,” the Gay People’s Union opened a venereal disease clinic on St. Paul Avenue in the Third Ward. Offering free testing, treatment, and consultations, the clinic catered to both gay and straight people and signaled a transition in sexual health between a focus on the treatment of existing diseases and the prevention of new cases. In 1981, the clinic relocated to Brady Street and became the Brady East Sexually Transmitted Disease (BESTD) Clinic. [19]

BESTD was one of the first local organizations to respond the AIDS crisis in Milwaukee, organizing volunteers and performing AIDS tests as early as 1983, the same year that city health officials claimed that the city had only two confirmed cases of the disease.[20] In 1984, the clinic formed the Milwaukee AIDS Project to help AIDS patients and promote safe sex practices among gay men. The Milwaukee AIDS Project eventually expanded to cater to both gay and straight people and was later rebranded as the AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin.[21]

Through the 1980s and 1990s, sexual health in the Milwaukee area was focused on AIDS prevention. By 1990, the city had pledged $43,000 to distribute condoms and safe sex literature to Milwaukee bars.[22] In 1996, BESTD opened a residence for AIDS patients in the Sherman Park neighborhood and, by 2005 the AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin had a staff of over 100.[23]

As of the early 21st century, sexual health focuses largely on education about and the prevention of STDs.[24] While certainly still an issue of concern, advances in medical treatment have made AIDS a largely manageable disease. Local governmental agencies still involve themselves in matters of sexual health, but private agencies—like Planned Parenthood and the BESTD Clinic—also deal with sexual health in a way that is open and accommodating to the public.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ The definition also includes the following: “Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled.” World Health Organization, “Sexual and Reproductive Health,” accessed July 27, 2016.

- ^ Judith Walzer Leavitt, The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1982).

- ^ “Health Department Has Many New Services for the People,” Milwaukee Journal, October 19, 1915, p. 16; George C. Ruhland, ed., Fortieth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Health (City of Milwaukee, 1916), 10-1.1

- ^ Ruhland, Fortieth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Health, 15.

- ^ Ruhland, Fortieth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Health, 10-11.

- ^ “To Protect Boys,” Milwaukee Journal, May 14, 1918, p. 11; “Social Hygiene Work Praised,” Milwaukee Journal, March 24, 1918, p. 10.

- ^ “US Combats Vice by Drastic Steps,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 15, 1918, part 2, p. 1.

- ^ “City Will Open a Night Clinic,” Milwaukee Journal, April 3, 1939, part 2, p. 1.

- ^ “Larger Clinic Laying Plans,” Milwaukee Journal, November 11, 1938, p. 10.

- ^ “Syphilis Drive in High Gear,” Milwaukee Journal, November 17, 1940, p. 14.

- ^ City of Milwaukee Department of Health, Milwaukee’s Health, (1941), p. 12-13.

- ^ “Social Dangers,” Milwaukee Journal, July 17, 1943, p. 1; “Venereal Disease Spread by Young Girls, Group Told,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 11, 1943, p. 10; “Venereal Disease in Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal, December 17, 1943, p. 22.

- ^ “Venereal Disease in Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal, March 19, 1947, p. 14.

- ^ “Facts You Should Know about the Dangers of Venereal Disease,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 24, 1949, p. 4.

- ^ Maggie Menard, “Planned Parenthood Growing at 50,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 11, 1985, p. 8; Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, Planned Parenthood Historical Timeline, accessed May 30, 2017.

- ^ “Gonorrhea Rate Jumps 36% in City,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 3, 1975, p. 1.

- ^ Katherine Skiba, “Hotline Offers Advice on Venereal Disease,” Milwaukee Journal Accent West, January 17, 1978, p. 4.

- ^ “Gonorrhea Rate Jumps 36% in City,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 3, 1975, p. 1.

- ^ “Clinic History,” BESTD Clinic website, accessed July 2, 2015.

- ^ “Clinic History,” BESTD Clinic website, accessed July 2, 2015; Lois Blinkhorn, “Milwaukee Not Immune to AIDS Outbreak,” Milwaukee Journal, May 31, 1983, part 2, p. 5.

- ^ “ARWC-AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin,” Milwaukee LGBT History website, updated May 16, 2005, accessed July 2, 2015.

- ^ Joe Manning, “Anti-Aids Campaign to Target Inner-City Taverns,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 4, 1990, p. 5.

- ^ “ARWC-AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin,” Milwaukee LGBT History website, updated May 16, 2005, accessed July 2, 2015.

- ^ See for example, Milwaukee Health Department, “Sexual Health Links,” accessed July 27, 2016.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.