For much of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, care for mentally or physically disabled individuals in the United States fell largely on the immediate family. In cases where families were unable to care for disabled members, the local community sometimes provided care. In some burgeoning cities of the early nineteenth century, charitable organizations coordinated such efforts, but even this support was usually designed to reinforce the family’s ability to provide care in their home.[1]

As the nineteenth century wore on, however, economic changes wrought first by the Market Revolution and later the Industrial Revolution fundamentally changed the nature of American cities—driving more individuals into urban areas to pursue wage work, concentrating poverty, and often creating greater anonymity. This was certainly the case for Milwaukee, where the population quickly boomed from just 55,000 residents in 1865 to 200,000 in 1890.[2] Such changes consequently overwhelmed the networks of small community charities that had previously helped support disabled individuals whose families could not afford their care. In the midst of these changes, urban dwellers began to embrace new methods of care for the mentally and physically disabled members of their communities.[3]

One of the few early exceptions to this rule of family care was the creation of schools for the blind and deaf. Such facilities stemmed from 1820s reform efforts in eastern cities to provide education and training to blind and deaf citizens. Like-minded Wisconsinites established a privately-run school for the blind in Janesville in 1849—the Wisconsin Institute for the Education of the Blind.[4] Just a few short years later, in 1852, it was followed by the opening of the Institute for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb in Delevan.[5] Over two decades later, Catholic Milwaukeeans were provided similar services at St. John’s School for Deaf Mutes, which opened its doors in 1876.[6] While these institutions were intended for educational purposes, Wisconsin legislators soon supported the establishment of numerous other “homes” that served a different purpose. While financially stable families often continued to provide in-home care to their disabled relatives, those individuals who lacked family support were increasingly institutionalized in facilities that were generally well-intentioned but often provided them dubious and sub-standard care.[7]

Mental Disabilities

The earliest attempts to care for insane residents involved confining them in county jails and poorhouses. In 1852, the Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors purchased 160 acres of farm land in Wauwatosa and ordered the construction of both a County Poor Farm and the Milwaukee County Hospital for the express purpose of housing the poor, sick, and insane.[8] Similar facilities were established in Waukesha County (1857) and Washington County in this same decade, while Ozaukee County followed a policy of farming out poor residents to neighboring families for care.[9]

Before long, however, city administrators and legislators grew critical of this approach. As early as 1852, the Milwaukee Sentinel sounded the alarm with reports of an insane man wandering the streets unattended, as well as the improper care of several insane residents at the old North Point poorhouse.[10] Milwaukee county residents were particularly concerned, and in 1856 the Milwaukee Sentinel reported as many as thirty-three insane persons residing in the county poorhouse.[11] The official state census, conducted in 1857, recorded ninety-seven insane persons and sixty-three “idiots” throughout the state. Sustained public outcry led the legislature to pass an act for the construction of a state hospital for the insane, which eventually opened on the shores of Lake Mendota in 1860.[12] When the demand for such services exceeded the facilities’ means, state legislators approved the construction of a second facility in Oshkosh in the early 1870s.[13]

When the state hospital was first established, insanity was considered by many medical professionals to be a curable condition.[14] As medical professionals came to realize the complexity of mental health, however, asylum care was increasingly looked upon as a means of sheltering “normal” society from the “dangerous” or “deviant” classes.[15]

This drove administrators in Milwaukee, Waukesha, and Washington counties to order the construction of separate facilities adjacent to their poor farms to house “incurably” insane inmates. Milwaukee built a separate facility for the chronically insane in 1888, and it opened a year later with at least one hundred inmates.[16] In Waukesha, poorhouse administrators advocated segregation of its insane residents as early as 1874, when they constructed a separate three-story facility equipped with “grated and barred cells for the insane.”[17] When the state legislature officially decided in 1902 that counties should provide care for the “chronic” insane, Waukesha officials went a step further and approved the construction of the Waukesha County Asylum for the Insane (1904).[18] Similarly, the Washington County Asylum for the Chronic Insane opened in West Bend in 1898.[19]

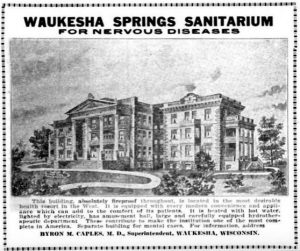

For many years, the state or county institutions were the only alternative to family care, but that changed in the late nineteenth century. A series of private facilities sprang up around the turn of the century. Institutions like the Milwaukee Sanatorium (1884), Sacred Heart Sanitarium (1893), Riverside Sanatorium (1898), Waukesha Springs Sanatorium (1904), Sanatorium Waldheim (1888), and the Oconomowoc Health Resort (1908) were established throughout the Greater Milwaukee area. Most specialized in treatment for mental and nervous disorders and generally endorsed some combination of water therapy, massage, exercise, and a connection with nature to treat their patients.[20] Some of these facilities served as predecessors to modern-day psychiatric and behavioral health centers.[21] While private funding ensured the survival of such facilities, state and county institutions struggled with inadequate funding, understaffing, and scandal.[22]

While Milwaukee residents, like most other Wisconsinites were calling for separate asylums for the insane, they largely ignored other mentally disabled residents of the county poorhouses until the mid-1890s.[23] Dubbed “feeble-minded,” “epileptic,” “imbeciles,” or “idiots,” these individuals were born with mental impairments that they believed would never be cured. Thus, their confinement to jails and poorhouses was of lesser concern to contemporaries until nearly two decades after the establishment of the state insane asylum. Lawmakers pitied the mentally impaired but thought them incapable of ever becoming useful and productive citizens.[24]

In spite of this prevailing opinion, there was a small group of reformers who went against the grain, pushing for institutionalization of the mentally handicapped in the 1870s and 1880s. Early advocates, like Governor Lucius Fairchild and the Wisconsin Teachers’ Association, suggested that these “poor creatures” could, in fact, be educated and the state should have a role.[25] This led to the introduction of a bill for the establishment of a state Home for the Feebleminded, which passed both houses of the state legislature in 1876 but was never signed into law.[26] Fairchild’s successors in the governor’s office failed to share his support for the cause and repeated attempts in the 1880s to establish a home were rejected, as opponents of the institution continued to insist that “cleanliness, fresh air, food, and warmth” were entirely sufficient for these “unteachable idiots who were unfit for family care.”[27] In their opinion, the county poorhouses could provide such cheap care.[28]

Efforts in the 1870s and 1880s to establish institutions for the developmentally disabled failed, and many continued to reside in facilities that were poorly suited to offer them much more than a roof over their heads. Finally, in 1895 the legislature approved the creation of the Wisconsin Home for the Feebleminded in Chippewa Falls.[29] A second facility—the Southern Wisconsin Home for the Feebleminded and Epileptics—was established in Union Grove, Wisconsin due to its proximity to such cities as Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, and Burlington.[30] Perhaps due to a greater need of such services, a few private homes for the feebleminded were established in southeastern Wisconsin in the early 1900s. These included the Lutheran Home for Feeble Minded and Epileptics in Watertown and the St. Coletta Institute for Backward Youth in Jefferson, both of which were established in 1904.[31]

Ironically, the success of this movement to educate and care for mentally disabled Wisconsin residents had less to do with recognition of their potential and much more to do with the growing prevalence of eugenic theory. By the late 1880s, mentally impaired persons were being lumped in with a broader category of “defectives” who represented both a moral threat and an economic burden on society.[32] Mentally disabled women were particularly troublesome, as they were thought to have voracious sexual appetites. Such beliefs led the State Board of Charities to urge the establishment of a “custodial asylum, at least for female idiots of child-bearing age,” to prevent the proliferation of mentally disabled persons.[33] Whereas legislators and charitable administrators had once pushed for families to shoulder such “burdens,” they now insisted that the “idiot child, with its repulsive appearance and disorderly habits [was] a demoralizing association for brothers and sisters.”[34] Families were now urged to institutionalize mentally disabled members and remove them from society. As a result of such characterizations, the population of the state Home for the Feeble-minded increased exponentially between 1900 and 1920. Beleaguered administrators soon began looking for more cost-effective ways to provide such care.[35]

They again believed the solution to their problem to be eugenics. In 1907, Wisconsin passed a law making it illegal for epileptic, feebleminded, or insane persons to marry and also making it a misdemeanor for such individuals to engage in sexual intercourse.[36] By 1913, legislators took this a step further, allowing the Board of Control to sterilize residents of state and county institutions as they saw fit. Their embrace of this procedure was motivated by a desire to parole as many residents as they could without fear of their reproducing.[37] While Milwaukee’s Archbishop Sebastian Messmer was one of the more vocal opponents of the practice, there were several Milwaukee-area doctors who advocated sterilization as a sensible progressive measure that held the “best promise of improving the race.”[38] Such advocates included Dr. Arthur W. Rogers, founder of the Oconomowoc Health Resort, Dr. Byron Caples of the Waukesha Springs Sanitarium, and the chief physician of the Milwaukee Hospital for the Insane, Dr. Richard Dewey.[39] Sterilization remained legal in Wisconsin until 1963.[40]

The Home for the Feebleminded’s goals shifted throughout the twentieth century. In 1923 it took on a new name (Wisconsin Colony and Training School) and a new philosophy of “rehabilitation and ultimate return of many high grade defectives to fields of extra-institutional usefulness.”[41] Like many other institutions, it was no stranger to criticism—about overpopulation, mistreatment, overuse of tranquilizing drugs, and its continued use of sterilization. By the late 1940s and early 1950s, alternative family care and community-based programs were just getting underway. These continued to grow throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and the older institutions shifted toward providing hospital-like care for “multiply-handicapped” or severely impaired individuals.[42]

Physical Disabilities

Institutionalization remained a popular solution for numerous dependent classes during the nineteenth century, but it was seldom employed for those who suffered from physical disabilities. There was one notable exception, however, in the wake of the Civil War. While many institutionalized care facilities were proposed as a means of fixing a social problem, one prominent Milwaukee-based institution was looked upon as a way to repay society’s debts to the many brave veterans who had been permanently injured in the course of war. The National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers welcomed its first residents in 1869.[43] Initially focused on housing Civil War veterans who had been disabled by injury or illness during their service, the NHDVS included barracks, a post office, a recreation building, a library, a theater, and a chapel.[44]

As the older generation of veterans dwindled, the NHDVS shifted its focus from housing to medical research and rehabilitation programs. By the 1930s, the facility became part of the larger federal Veterans Administration. Over the next few decades it expanded vastly to accommodate the growing number veterans from World Wars I and II, the Korean War, and Vietnam.[45] Wood Hospital (as it was known from the 1930s through the mid-1980s), offered treatments for veterans suffering from spinal injuries, paralysis, and various other severe physical and mental disabilities. A new building was completed in 1966, and the Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center, as it was renamed in 1984, remains in operation today, providing medical care to veterans of the Second World War and the wars in Korea and Vietnam, as well as America’s most recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.[46]

The NHDVS is the most prominent institution for disabled veterans, but it was not the only facility in operation in the greater Milwaukee area. In 1919, the government requisitioned the Rest Haven Sanatorium in Waukesha and transformed it into a 240-bed hospital for veterans of the First World War suffering from mental and nervous disorders. Formerly a spa resort, Rest Haven offered psychological treatment to veterans for nearly a decade.[47]

Outside of the veterans’ facility, nineteenth-century Milwaukeeans who suffered from physical disabilities—whether congenital or accident-related—were much less frequently institutionalized. When families could not support them, they often ended up in county almshouses, and their children could end up in one of Milwaukee’s many orphanages—but their condition was simply not seen as a threat to the greater community.[48] As industrialization ramped up and the number of injured workers grew, however, the state began to take notice.[49]

By the turn of the twentieth century the sheer numbers of physically disabled laborers were such that they put a strain on charitable resources.[50] By 1907, however, progressive reformers began pushing industries to assume more of the burden of care.[51] Following the example of some of Milwaukee’s larger industrial enterprises, like International Harvester and Pfister & Vogel, which had established programs for guaranteed medical and financial assistance to injured workers, Wisconsin legislators eventually adopted the nation’s first constitutionally upheld workmen’s compensation bill in 1911.[52] The measure introduced a no-fault compensation plan for any and all workers who were temporarily or permanently disabled on the job. In doing so, the state provided disabled workers with access to financial resources that typically helped them avoid the worst economic consequences of being disabled.[53]

The state’s approach to dealing with physically disabled workers marked the beginning of an attitudinal shift about how to best handle disabled Wisconsin citizens as a whole. From the turn of the twentieth century onward, legislators and disability advocates began talking about the disabled in terms of usefulness and productivity. Some argued that certain groups of disabled persons were permanently categorized as useless and dependent. Others suggested that with proper care, such individuals could be restored to productivity, leading an independent life, or at least providing for their own maintenance.[54] Gradually, this philosophy became the dominant approach in legal, medical, and social dealings with disabled Wisconsinites of all classes as a wide array of community-based support programs replaced institutionalization in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Elected officials often followed the lead of independent charitable organizations and advocacy groups, including the Goodwill Corporation, the Junior League of Milwaukee, and the Badger Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired (now the Badger Association-Vision Aware).[55] Milwaukee’s Curative Care workshop gradually expanded its services to adults (1920), eventually reaching out to serve homebound patients (1928), injured defense workers during World War II, veterans with speech impairments (1945), children with cerebral palsy (1947), the developmentally disabled (1970s), and many other groups of disabled citizens.[56] By the 1940s and early 1950s, many other local agencies emerged with similar programming, designed to provide disabled citizens greater agency and independence. The Eisenhower Center, for example, began offering education, training programs, and employment opportunities for individuals with cerebral palsy in the 1950s.[57]

This advocacy is most obvious in the struggle for access to education. Milwaukee reportedly established the state’s first special education classrooms for “mentally retarded” children as early as 1906.[58] In 1917, the state passed a broader program which provided financial aid to schools that created such classes.[59] Throughout the next two decades, such offerings multiplied; particularly in urban areas like Milwaukee, where the public school system began developing a three-track educational system for “regular,” “slow,” and “special needs” learners.[60]

The limited availability and eligibility restrictions on these early programs left a large number of mentally disabled children unserved until parental advocacy groups emerged at mid-century. The Wisconsin Association for Retarded Children (WARC), founded in 1949, led the charge by calling for vast improvements to the employment opportunities, educational programs, and community services available for more severely disabled children. Working with the Jewish Vocational Services (later Milwaukee Center for Independence), WARC established a program to demonstrate how children with an IQ below 50 could learn, prompting a change in state law that allowed such students access to public schools.[61] Such parental advocacy brought about a significant expansion of access to education—in 1951, the state authorized home-bound instruction to physically disabled children, and it expanded such access to the mentally disabled in 1959.[62] For both physically and mentally disabled Wisconsin children, however, the fight for equal access to education was not completed until the passage of Chapter 115 in 1974, which ensured that “all special students between the ages three and twenty-one with disabilities were required to receive a free public school education.”[63] In spite of such victories, disabled residents of Milwaukee, and those around the state, are still struggling for parity in education, as voucher schools have been permitted to reject disabled students due to an inability to serve their special interests.[64]

Although equal access to education was one of the foremost concerns, it was not the only issue addressed by advocacy groups over the past fifty years. The Wisconsin Association for Retarded Children, the Milwaukee Center for Independence, and numerous other groups also worked to provide sheltered workshops which allowed more severely impaired adults to find employment; and the WARC led the charge in the 1960s and 1970s for greater state resources for families of the severely disabled and the establishment of communal living opportunities.[65] Working together, these disability rights advocates pushed for the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, granting disabled Americans protection from discrimination.[66] These efforts have resulted in greater agency on the part of Wisconsin’s disabled citizens. While great strides have been made to overturn able-bodied prejudice and secure equality for the disabled in the greater Milwaukee area, and the country at large, these advocates continue to push for greater accommodation of disabled citizens by providing equal access to education, housing, employment, and opportunity.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Ellen Hotzman, “A Home away from Home,” Monitor (March 2012), accessed August 10, 2018; David J. Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum; Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic (Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1971).

- ^ “A Brief History of Milwaukee,” Children in Urban America, accessed August 15, 2018.

- ^ Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum.

- ^ Tom Hanson, “History [of the Wisconsin Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired],” Wisconsin Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired website, accessed April 3, 2018. In February of 1850, students from the school demonstrated the school’s value, earning state support for the establishment of the Wisconsin Instituted for the Education of the Blind.

- ^ Anne V. Rugg, Children of Misfortune: One Hundred Years of Public Care for People with Mental Retardation in Wisconsin, 1871-1971 (Madison, WI: The Wisconsin Council on Developmental Disabilities, n.d.), 3.

- ^ Rev. M. M. Gerend, In and about St. Francis: A Souvenir (Milwaukee: King, Fowle & Co., 1891).

- ^ Hotzman, “A Home away from Home”; Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 6.

- ^ Sarah Klingman Cole, “Land Use Analysis of the Milwaukee County Institutional Grounds: A Chronological and Spatial Depiction of Cultural Change” (MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015), 12.

- ^ Western Historical Company, The History of Waukesha County, Wisconsin (Chicago, IL: Western Historical Company, 1880); Carl Quickert, ed., Washington County, Wisconsin: Past and Present (Chicago, IL: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1912), 224. The exact date of the Washington County Poor Farm’s construction is uncertain; “Without Means for Life or Death,” Historical Perspectives 28, no. 2 (Port Washington, WI: Port Washington Historical Society, 2017), 1.

- ^ Dale Wendell Robison, “Wisconsin and the Mentally Ill: A History of the ‘Wisconsin Plan’ of State and County Care, 1860-1915” (PhD diss., Marquette University, 1976), 26. The Sentinel claimed that several insane residents were confined to malodorous cells, while others were provided with inadequate clothing. One man was found naked on a bed of straw.

- ^ Robison, “Wisconsin and the Mentally Ill,” 38.

- ^ Robison, “Wisconsin and the Mentally Ill,” 41-44.

- ^ Robison, “Wisconsin and the Mentally Ill,” 73.

- ^ Robison, “Wisconsin and the Mentally Ill,” 42.

- ^ Robison, “Wisconsin and the Mentally Ill,” 47.

- ^ Cole, “Land Use Analysis of the Milwaukee County Institutional Grounds,” 13-14.

- ^ Western Historical Company, The History of Waukesha County, Wisconsin, 557.

- ^ Waukesha County Wisconsin Genealogy, “Poor Farm, Pauper Cemetery, Insane Asylum,” Links to the Past Genealogy website, accessed April 10, 2018.

- ^ Quickert, Washington County, 224.

- ^ Jon Van Beckum, “Pioneers and Visionaries: A History of Mental Health at: the Milwaukee Sanitarium; the Milwaukee Psychiatric Hospital; and the Aurora Psychiatric Hospital, 1884 to 2009,” p. 5, Aurora Health Care Digital Repository, April 2015, accessed April 10, 2018; Cynthia Sommer, “Riverside/Shorewood Sanitarium,” Murray Hill Neighborhood Association website, April 2015, accessed April 10, 2018; State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Historic Preservation Division, “Sanger, Casper M., House,” National Park Service Digital Asset Management System (83004357); “Waldheim Park, Souvenir Prospectus,” accessed April 10, 2018; BizTimes Staff, “Oconomowoc Health Resort, Glance at Yesteryear,” BizTimes, June 12, 2017, accessed April 10, 2018; Bobby Tanzilo, “Urban Spelunking: Layton Boulevard Tunnels,” OnMilwaukee.com, February 17, 2014, accessed May 27, 2018.

- ^ Jon Van Beckum, “Pioneers and Visionaries: A History of Mental Health at: the Milwaukee Sanitarium; the Milwaukee Psychiatric Hospital; and the Aurora Psychiatric Hospital, 1884 to 2009,” Aurora Health Care Digital Repository, April 2015; BizTimes Staff, “Oconomowoc Health Resort, Glance at Yesteryear,” BizTimes, June 12, 2017, accessed April 10, 2018. See also Waukesha Daily Freeman, June 5, 1923, 1.

- ^ Robison, “Wisconsin and the Mentally Ill,” 65-66.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 3-5.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 3.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 7-8.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 5.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 8.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 9.The organization first started providing “care, custody and training of the feeble-minded, epileptic, and idiotic of the state,” in 1897 (11).

- ^ “Southern Wisconsin Center for the Developmentally Disabled,” Asylum Projects, accessed August 15, 2018.

- ^ “Lutheran Home for Feeble Minded and Epileptics,” Asylum Projects, accessed August 15, 2018; “St. Colletta Feeble-Minded School,” Asylum Projects, accessed August 15, 2018.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 8-9.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 8.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 9.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 15-23.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 16.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 17-23.

- ^ Rudolph J. Vecoli, “Sterilization: A Progressive Measure?,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 43, no. 3 (Spring 1960): 197.

- ^ Vecoli, “Sterilization,” 194, 197.

- ^ Lutz Kaelber, “Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States: Wisconsin,” University of Vermont website, accessed April 10, 2018.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 21.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 24-42.

- ^ James Marten, Sing Not War: The Lives of Union and Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 161.

- ^ 5000 West National Avenue, Wisconsin State Register of Historic Places, Wisconsin Historical Society, accessed August 12, 2018.

- ^ “History of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers,” National Parks Service website, https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/veterans_affairs/history.html, now available at https://home.nps.gov/articles/history-of-disabled-volunteer-soldiers.htm, last accessed April 11, 2019.

- ^ Dozen Decades of Dedication, 1867-1987: Milwaukee in Service of the Veteran (Milwaukee: The Center, 1987), 16-17.

- ^ “Veterans Hospital No. 37,” Asylum Projects, accessed April 10, 2018.

- ^ Karalee Surface, “In Harm’s Way: Wisconsin Workers and Disability from the Gilded Age to the Great Depression” (PhD diss., Marquette University, 2015), 75-95.

- ^ Surface, “In Harm’s Way,” 82.

- ^ Surface, “Perils of Production,” in “In Harm’s Way.”

- ^ Surface, “In Harm’s Way,” 82.

- ^ Surface, “In Harm’s Way,” 76-78.

- ^ Surface, “In Harm’s Way,” 127.

- ^ Surface, “Societal Perceptions of Disability,” chap. 3 in “In Harm’s Way.”

- ^ “Our History,” Goodwill Industries of Southeastern Wisconsin, Inc., accessed June 1, 2018; “Curative Care Has a Rich History,” Curative Care, accessed June 1, 2018; “Vision Forward Association,” Doors Open Milwaukee, accessed June 1, 2018; Housing Authority of the City of Milwaukee, Navigating Through Change, Annual Report 2008-2010, Housing Authority of the City of Milwaukee website, accessed June 1, 2018.

- ^ “Curative Care Has a Rich History,” Curative Care, accessed June 1, 2018.

- ^ “About Eisenhower Center: History,” Eisenhower Center, accessed June 1, 2018.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 17.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 17.

- ^ “Exceptional Education Department History,” University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, School of Education, http://uwm.edu/education/academics/exceptional-edu-dept-history/, accessed June 1, 2018.

- ^ Wisconsin Disability Association, “1949-Present,” Wisconsin Disability Association, accessed June 1, 2018.

- ^ Rugg, Children of Misfortune, 34.

- ^ Barbara Pellegrini, et al., “The Mothers of Chapter 115: How Wisconsin Mandated Special Education for All Children with Disabilities,” Wisconsin Magazine of History (Spring 2016): 12.

- ^ “Milwaukee Voucher Schools Still Discriminate against Students with Disabilities,” ACLU Wisconsin, July 20, 2015, accessed June 1, 2018.

- ^ Wisconsin Disability Association, “1949-present,” accessed June 1, 2018; “History,” Milwaukee Center for Independence, accessed June 1, 2018.

- ^ “What Is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)?,” ADA National Network, accessed June 1, 2018.

For Further Reading

Grob, Gerald N. The Mad among Us: A History of the Care of America’s Mentally Ill. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Marten, James. Sing Not War: The Lives of Union and Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Nielsen, Kim E. “Property, Disability, and the Making of the Incompetent Citizen in the United States, 1860s-1940s,” in Disability Histories, edited by Susan Burch and Michael Rembis. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Robison, Dale Wendell. “Wisconsin and the Mentally Ill: A History of the ‘Wisconsin Plan’ of State and County Care, 1860-1915.” PhD diss., Marquette University, 1976.

Rose, Sarah F. No Right to Be Idle: The Invention of Disability, 1840s-1930s. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Rothman, David J. The Discovery of the Asylum; Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, 1971.

Rugg, Anne V. Children of Misfortune: One Hundred Years of Public Care for People with Mental Retardation in Wisconsin, 1871-1971. Madison, WI: The Wisconsin Council on Developmental Disabilities, n.d.

Schweik, Susan. The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2009.

Surface, Karalee. “In Harm’s Way: Wisconsin Workers and Disability from the Gilded Age to the Great Depression.” PhD diss., Marquette University, 2015.

Witt, John Fabian. The Accidental Republic: Crippled Workingmen, Destitute Widows, and the Remaking of American Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.