Gangs, once called “boy gangs” to distinguish them from adult criminal gangs, have been a feature of urban America since the nineteenth century. The notion of gangs has always raised a number of issues, including race and ethnicity, economic opportunity, criminal behavior, and ultimately political decisions regarding the use of resources to address gangs as a social problem. For some, gangs represent the expression of deviant behavior among young boys.[1] For others, the development of gangs is found in the more complex interactions among a number of institutions and processes in a community, e.g., poverty, segmentation of the labor market, failure of an educational system, and insufficient criminal justice responses to larger social and economic conditions within a community. Most of what we know about gangs in Milwaukee in the first hundred years of the metropolitan area’s existence is episodic, although there has been more research on urban gangs nationally since the 1930s and locally even more recently.[2] What historical evidence there is does suggest that the intricate relationships among organized street gangs, politicians, and volunteer fire companies found in early nineteenth century Eastern cities such as New York and Philadelphia did not replicate itself in a later-developing Milwaukee.[3]

The urban economy significantly influenced the nature of gang phenomena in spite of locale. Throughout Milwaukee’s industrial heyday, from the early twentieth century through the 1970s, gangs were organizations that working class youngsters joined in their teen years. Growing up, in the end, “meant being able to ‘mature out’ of the gang: get a decent job, get married, and move into a better neighborhood.”[4] The strength of Milwaukee area’s industrial economy fostered assimilation for many white immigrants (largely German, Irish, Slavs, Poles, and Jews) and the nascent development of a “black proletariat” of migrants from the South as the cotton economy mechanized.[5] Jobs remained plentiful in Milwaukee after World War Two. Most residents, established as well as new migrants, enjoyed decades of prosperity.

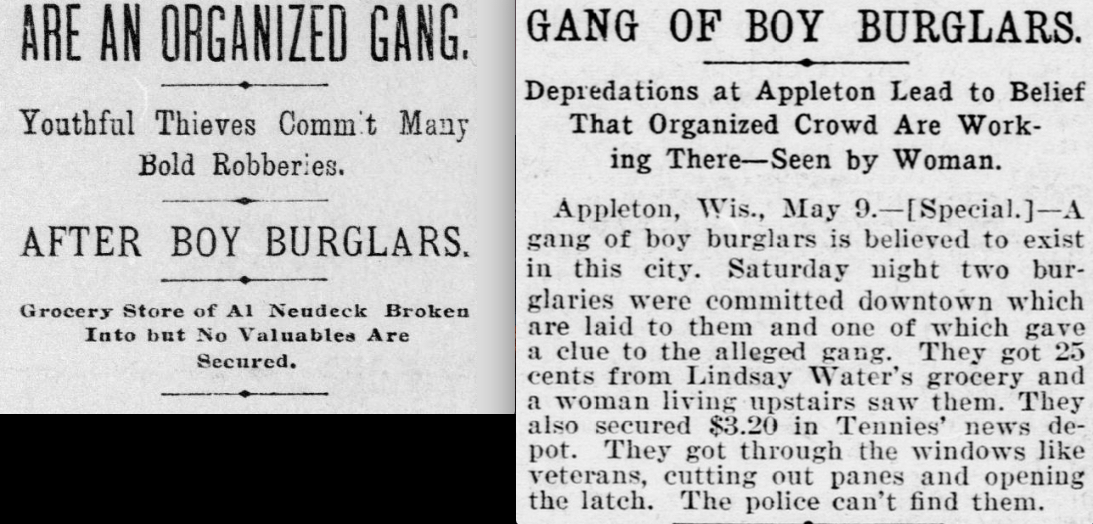

Historically, gang activity ranged from the informal and the disreputable to the illegal and violent. Neighborhood or high school rivalries that could lead to intense sports competitions or even fistfights seems to have been accepted as routine male behavior among teenagers in the first half of the twentieth century. Yet by the end of the 1920s, outright criminal behavior had become relatively common among groups of Milwaukee boys, with some participants as young as nine or ten. Not surprisingly, these criminal behaviors grew during the early years of the Great Depression. Sometimes, it was simple mischief such as running through the Post Office, overturning carts and produce along Commission Row, or breaking street light globes. Authorities became far more anxious when “marauding gangs” broke into boxcars, grocery stores, garages, and residences with greater frequency. Smaller children had their lunch money extorted. Swiping money from cash registers or cigarettes out of rail cars led to profits that could reach hundreds of dollars, even thousands on rare occasions. Citizens were repeatedly warned to lock their automobiles as car thefts increased when weather conditions improved each spring. According to police and juvenile court reports, hot spots of juvenile delinquency included the Third Ward and a manufacturing district near the Holton Street viaduct, although teenagers in suburbs were also caught in criminal activities, especially car thefts.

Explanations for these behaviors during the 1930s centered upon an individual’s “low intelligence” as well as parental failures, with the favorite punishment for more serious cases an assignment to the Industrial School in Waukesha. Parental responsibility remained the favorite explanation for gang activity into the 1950s, accompanied by a civic sigh of relief that there were no adult gangs into which these troubled youth might graduate. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, female gangs were absent from local conversations over teenage crime, although juvenile delinquency among teenage girls during World War Two drew considerable attention because of the sexual nature of these incidents. By the 1960s, male and female as well as racially distinctive gangs became threatening enough in the Marquette University area west of downtown to warrant demands from the student government for better security and escorts for nuns who took evening classes.[6]

Academic investigations into youth gangs originated with sociologists at the University of Chicago, a cohort of scholars that came to be known as the “Chicago School.” These men and women dissected every corner of urban communities, resolving to understand urban problems and, along the way, uncovering methods to investigate and evaluate social ills.[7] Their analytic framework offered strategies for students to “go native,” researching communities by exploring them in person and documenting how and why certain dysfunctional behaviors occurred. Within this library of research, social scientists sought to understand why boys joined gangs, what purposes the gang served, and what needs were being addressed.[8] The Chicago School remained dominant in the popular understanding of youth gangs from the 1920s through the early 1960s. In this view, gangs were largely viewed as products of their environments.

By the early 1980s, however, the reasons why gangs existed became almost secondary to concerns about the changing social, political, and economic realities of American cities. Gangs became emblematic of a mounting list of social ills. In Milwaukee and across the Midwest and Northeast, foreign and Sunbelt competition for manufacturing jobs decimated the secondary economic sector. Writers documented how, throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, major urban metropolitan areas seemed under economic attack.[9] Additionally, for the first time, gangs were being associated almost exclusively with urban youth of color: African-Americans and Latinos.

In this environment, local activist and University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee graduate student John Hagedorn undertook a multiple-year research project on Milwaukee gangs. This work is still the most definitive work ever done on Milwaukee gangs. His analysis traced the development of Milwaukee gangs from street corners to break-dancing events to institutionalization over the course of the 1980s. Hagedorn drew attention to a misdirected criminal justice response, as evidenced by questionable police practices and short-sighted political solutions to the “gang problem.”[10]

Hagedorn and his interviewees tried to explain how the institutionalization of gangs in Milwaukee was directly correlated to the loss of living wages among so many urban dwellers, with the resulting sense of hopelessness “when work disappears,” to use sociologist William Julius Wilson’s phrase.[11] As such, gangs proliferated, but now for the first time members stayed affiliated into adulthood. As noted by Hagedorn, for most of the affiliated members, the primary source of income was drug dealing and activity in an informal economy outside the mainstream of society. In the end, gangs recruited not so much troubled youth as described by earlier research but had became part of a community’s social fabric, among citizens who were reeling from unemployment, racism, segregation, and inequality.

Studies of the quality of life among Milwaukeeans during the first part of the twenty-first century underscore the poor conditions affecting large numbers of African-Americans and Latinos even as the city became more segregated, with concentrated poverty as the province of African-American and Latino neighborhoods.[12] Gangs have been institutionalized in Milwaukee since the early 1980s as a result of segregation, poverty, and inequality. There is no reason to believe they will be significantly decreasing in size and scope in the twenty-first century unless the local economy improves. In fact, current urban research and gang research suggests an ominous future, with limited opportunities available for urban youth, not only in Milwaukee and the United States but the rest of the world as well.[13] Many urban youth are “stuck in place,” and the chances for changes in the quality of urban life are bleak if traditional social institutions are not strengthened.[14]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ See John Hagedorn and Perry Macon, People and Folks: Gangs, Crime and the Underclass in a Rustbelt City (Chicago, IL: Lake View Press, 1988). Hagedorn and Macon also note how gang research has always been limited when understanding girl gangs. Most of the extant literature addresses gangs in the context of adolescent boys, an obvious limitation in the research. In addition, examine the work of Frederick Thrasher, The Gang (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1927, 1963). According to John M. Hagedorn, “Gang Violence in the Postindustrial Era,” Crime and Justice, 24 (1998), 370, “American gangs and their violence were basically the product of the problems of young people acculturating to life in poor urban communities. The classic gang was a rebellious, working-class, teenage male peer group.”

- ^ Research on gangs includes explanations that move well beyond personal choice of young people to exhibit deviant behavior or drop out of conventional institutions in society, i.e., attend school, join the labor force, marry and have children, and affiliate with a church. Instead, the research suggests that, like other social phenomena, gang creation is a function of many forces working in a society directly and disproportionally on some in that community.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948); Tyler Anbinder, Five Points: The 19th Century New York City Neighborhood that Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum (New York, NY: Penguin Group, 2002); Herbert Asbury, The Gangs of New York (New York, NY: Capricorn Books Edition, 1970).

- ^ Hagedorn, “Gang Violence in the Postindustrial Era,” 371, explains: “The gang was a product of the lack of controls over youthful play, but it was also a kind of anticipatory rebellion by boys against a dreary future life as men in the factory…Gangs were shaped by both the class structure and the varying means of access by ethnic groups to industrial jobs. Industrial-era gangs were an adolescent by-product of the difficulties experienced by immigrant and migrant groups in realizing the American Dream.”

- ^ Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-1945, 2nd ed. (Urbana, IL: University. of Illinois Press, 2007).

- ^ Milwaukee Journal, May 24, 1929; August 26, 1932; August 27, 1932; October 7, 1932; October 14, 1932; May 26, 1935; April 16, 1937; April 28, 1940; April 26, 1951; August 31, 1951; and July 11, 1957; Charissa M. Keup, “Girls in ‘Trouble’: A History of Female Adolescent Sexuality in the Midwest, 1946-64” (Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 2012); Thomas J. Jablonsky, Milwaukee’s Jesuit University (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2007), 368-69.

- ^ The Chicago School is noted for their emphasis on examining social problems, such as crime and deviance, as a function of the environments where people resided. This analytical tradition was the first to systematically explore the relationship between the conditions under which people lived and a host of social maladies, such as mental illness, alcoholism, divorce, crime, and later gang formation.

- ^ See William Whyte, Street Corner Society (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1943) and later Elliot Liebow, Tally’s Corner: A Study of Negro Street Corner Men (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1967).

- ^ See William Julius Wilson, The Declining Significance of Race (Chicago, IL: University Chicago Press, 1978) and The Truly Disadvantaged (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

- ^ Hagedorn and Macon, People and Folks.

- ^ See William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996).

- ^ See, for example, Marc Levine, The Shame of Milwaukee: Race, Segregation, and Inequality (Milwaukee: Center for Economic Development, 2015). One of the most glaring facts is the concentrated poverty is localized in specific neighborhoods and has been consistent for many decades.

- ^ See John M. Hagedorn, A World of Gangs: Armed Young Men and Gangsta Culture (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008) and The Insane Chicago Way: The Daring Plan by Chicago Gangs to Create a Spanish Mafia (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

- ^ See for example, Patrick Sharkey, Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress toward Racial Equality (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

For Further Reading

Hagedorn, John, and Perry Macon. People and Folks: Gangs, Crime and the Underclass in a Rustbelt City. Chicago, IL: Lake View Press, 1988.

Hagedorn, John. The Insane Chicago Way: The Daring Plan by Chicago Gangs to Create a Spanish Mafia. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Sharkey, Patrick. Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress toward Racial Equality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Wilson, William Julius. When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.