Milwaukee attained its official municipal status in 1846. As with many fundamental urban changes of the era, the catalyst for transformation from village to city was a series of social crises and territorial fights. In little more than a decade, Milwaukee had grown from a mere trading post to a community that would reach 20,000 by 1850. At that time, roughly two-thirds of its people were foreign-born, mostly German. The area faced mounting health, welfare, and infrastructural demands—including a smallpox epidemic, law enforcement and fire protection needs, the desire for sufficient public schools, and demands for safer roads and a shipping port. The collective cry for better government reached a crescendo in 1845 following the so-called “Bridge Wars”—repeated incidents where residents on one side of the Milwaukee River sabotaged efforts of their counterparts on the other to connect the two; this exposed a rift that village leaders hoped to span with a larger vision.[1]

Prominent residents and their working class neighbors disputed both who should have a say in the new government and how much power it should wield. Immigrants, who were heretofore allowed to vote in a popular referendum, opposed language that reduced or eliminated their subsequent voting rights; state legislators challenged the proposed three-year terms for aldermen. The final charter allowed foreign-born residents who worked for the city and paid taxes to vote, and determined that elections would be held on an annual basis. In its initial form, the Common Council had three elected representatives from each of five wards. These aldermen retained exclusive authority to commission projects, hire workers, and levy special taxes within their own wards.[2] Thus the city resembled a confederation more than a unified municipality. The arrangement of separate budgets (i.e., revenues and expenditures), combined with the fact that aldermen served without pay, encouraged bribe-taking and favoritism.[3] In an effort to address this, between 1858 and 1874, Milwaukee briefly experimented with adding a second legislative chamber. The 1874 charter did away with this body and the corruption continued unabated.

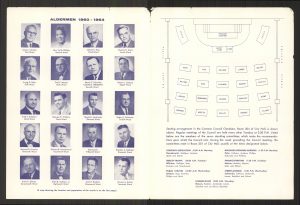

Since its inception, the Common Council’s configuration has often changed. New charters and state statutes in turn altered: (a) term lengths (from one to two to four years), (b) the relative powers of council and mayor, (c) the number of wards, (d) the number of aldermen from each district, and (e) partisan affiliations in municipal elections (at least on paper).[4] The Council’s powers and concerns have also changed, in keeping with social and economic adjustments in the region and country. Over its first 170 years, the Common Council has addressed: providing safe drinking water to residents; building a sewerage treatment system and a garbage incinerator plant; preventing communicable diseases (including milk-borne tuberculosis); establishing parks; managing house construction for a rapidly growing populace; weathering several economic depressions; and, to some extent, overseeing transit improvements. Other issues have included maximizing bureaucratic efficiency and reducing corruption (e.g., through a civil service exam); instituting zoning regulations; annexing outlying land for industrial and residential use; providing for public education; advancing public safety (police and fire); adopting civil rights (i.e., fair housing) measures; and continuously repairing infrastructure—particularly roads.

Despite the city’s substantial size, the powers of the Common Council and mayor continue to be constrained by state laws since, according to the state constitution, the city is a creation of the state. While the 1924 Wisconsin Home Rule amendment granted cities the power to pass and amend their own charters without first consulting the state and to otherwise act autonomously in many ways, courts have interpreted this provision narrowly, allowing the state to usurp control over any matters “of statewide concern.”[5]

Today the Council and its committees meet every fourth week, except for August and the winter holidays.[6] As the law-making body for the city, the Common Council maintains standing, special, and citizen committees to study and report on public policy issues. These reports are often transformed into bills which become ordinances if passed by a majority and signed by the mayor, a process parallel to both state and federal government structures.[7]

Two of the Council’s most prominent leaders were Cornelius L. Corcoran, Council president for 40 years, and publisher and historian William George Bruce.[8] Many Wisconsin politicians got their start in politics as Milwaukee aldermen. Demographically, the face of the Common Council has also changed considerably. Although the city’s founders were primarily “Yankees” and these individuals populated City Hall, by the late 1800s a second generation of Germans was rising to public office. A generation later, Polish leaders joined them. Although as early as 1912 Wisconsin considered whether women should be allowed to take part in politics, they did not win the vote until ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920. Even so, it took another 40 years before Milwaukee elected its first female alderperson. World War II-era jobs lured thousands of African American workers from the South as part of the Great Migration, but these newcomers did not play a formal role in city governance until 1956 when Vel Phillips became both the first African American and the first female city council member.

As of 2017 the Council is more diverse. Several members are of African American and Latino heritage, although representation by ethnicity and gender is in no wise proportional to the city’s current population.[9] The challenges facing the city and thus the Milwaukee Common Council in the twenty-first century primarily involve money: (1) providing services for growing impoverished and aging populations—despite a shrinking tax base due to deindustrialization, increased chronic unemployment, and sharp cuts to shared state revenues, and (2) attracting and retaining businesses and talented workers for those businesses by providing the services, entertainment, housing, and transportation options that this sector demands. These two divergent goals represent what perhaps might be considered Milwaukee’s current sectional divide or “Bridge War.” Finding common ground between such divergent interests is not impossible, but it is a problem that cries out for fresh voices who can infuse original ideas into the local governance process.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1965).

- ^ Laurence Marcellus Larson, “A Financial and Administrative History of Milwaukee,” Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin, no. 242 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 1908), 26, last accessed April 14, 2016.

- ^ No greater example of such corruption can be found than the Council’s 1900 streetcar franchise law, which members accepted while police barred the entry of enraged citizens. Specifically, the Council voted on January 2, 1900 to grant The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Co. (TMER&L Co.) an exclusive 35-years (January 2, 1900-December 31, 1934) contract. The Council was aware of stiff opposition since several people had already sought and obtained court injunctions against the vote. The Council took this action while suspending the formal rules of order and physically locking the public out of Council chambers. Meanwhile corporate executives looked on and Mayor David S. Rose stood by to sign the legislation on the spot. A criminal trial many years later proved the existence of bribes for this transaction, but no official ever served jail time.

- ^ At one point there were as many as 39 aldermen—three from each of 13 districts, originally called wards but later changed to Aldermanic districts. Today only one alderman represents each of the 15 districts consisting of approximately 40,000 people. Elections take place every four years on the first Tuesday of April. A non-partisan law passed in 1912 appeased a temporary coalition of Republicans and Democrats eager to oust the city’s Socialists, who had won increasing numbers of votes since 1898, culminating in winning a majority in the Common Council and the mayor’s seat in 1910. John D. Buenker, “Cream City Politics: A Play in Four Acts,” in Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past, ed. Margo Anderson and Victor Greene (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009), 28. Although aldermanic elections remain officially non-partisan, party affiliation is usually evident. See A. Clarke Hagensick, “Influences of Partisanship and Incumbency on a Nonpartisan Election System,” Western Political Quarterly 17, no. 1 (Mar. 1964): 117-124. (Study of Milwaukee election patterns suggesting that candidates at least once associated with a party fare better than those unaffiliated at all.) See also “Common Council,” Official Website of the City of Milwaukee website, last accessed February 24, 2017.

- ^ The state also exercises a plethora of powers over city governments via administrative agencies. The most evident example of this is the Wisconsin Public Service Commission which has determined the course of transportation development in Metropolitan Milwaukee since 1907 and once again stepped in to prevent city construction of a new streetcar system. See TRANSIT, TRANSPORTATION, and Karen W. Moore, “Missed Connections: The ‘Progressive’ Derailment of Public Transit in Metropolitan Milwaukee during the Electric Street Railway Era,” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2011).

- ^ 2015 Common Council Calendar, Official website of the City of Milwaukee, last accessed February 24, 2017.

- ^ City Council elections are held every four years on the first Tuesday in April (even years). Standing committees include: Community and Economic Development; Licenses; Public Works; Finance and Personnel; Public Safety; Steering and Rules; Judiciary and Legislation, and Zoning, Neighborhoods & Development. “Common Council,” Official Website of the City of Milwaukee website, last accessed February 24, 2017.The city’s water system was probably its earliest and possibly its most significant achievement, even to date. One health measure involved killing tuberculosis in milk to prevent the disease from spreading in the city. Still, Milwaukee, p. x.

- ^ See William George Bruce, History of Milwaukee, City and County, vol. 2 (Chicago: S.J. Clark Publishing Co., 1922).

- ^ In large part, the changes in the city’s political form and duties are attributable to the phenomenal increase in the city’s population; it grew from 10,000 at its founding to 71,440 residents by 1874 and swelled to a remarkable 741,324 by 1960, at which point Milwaukee was considered the eleventh largest U.S. city. While losing many seats in 1912, including the mayor’s office, the Socialist Party held the mayoral office for 38 of 50 years (24 of those under Mayor Daniel Hoan) and several aldermanic seats as well, until the retirement of the city’s third and last Socialist mayor—Mayor Frank Zeidler in 1960.

For Further Reading

Bruce, William George. History of Milwaukee, City and County. 2 vols. Chicago, S.J. Clark Publishing Co., 1922.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.