According to transit historian Zachary Schrag, mass transit “generally refers to scheduled intra-city service on a fixed route in shared vehicles.”[1] Since 1860, opposing political and economic forces significantly shaped the provision of transit in the Milwaukee metropolitan region. These forces included changes in available and economically viable technologies, advocates for public versus private ownership, and conflicting views regarding which level of government—municipal, county, or state—was most appropriate to oversee transit services.[2]

Prior to Milwaukee’s incorporation in 1846, regional mass transit consisted of private horse-drawn omnibuses on unpaved roads. Omnibus businesses succeeded by overcoming the challenges of climate—and mud—primarily due to the invention of private tollways called “plank roads”; these were dirt roads lined with wheel-spaced boards to create a relatively smooth surface over uneven and muddy terrain. In 1860, George Walker, one of the city’s founders and early mayors, introduced the first streetcars on public roads. These horse-drawn rail cars ran on permanent tracks set flush with the street surface and spaced the same distance as traditional horse-cart wheels. This service thrived in no small part because it coincided with the increase in national and intercity railroad passenger and freight travel and the need to move soldiers during the Civil War.[3]

Rails were permanent but private fixtures on public thoroughfares. Like other cities, Milwaukee charged for and regulated their installation by granting or denying special franchises to streetcar companies. As Milwaukee’s population and geographical size grew due to its burgeoning international wheat trade, streetcar franchise competition became fierce. Many local political leaders invested in competing lines or made their franchise grants on the basis of kickbacks from investors. The four major lines operating in Milwaukee after the Civil War were: (1) the Cream City Railroad Company, backed by Democratic Party boss Ed Wall; (2) the Milwaukee City Railway Company, owned by John A. Hinsey, another Democratic Party leader; (3) the Whitefish Bay Railway Company, funded by prominent businessmen and Republicans Charles Pfister, Fred Vogel, and Frederick Pabst, and (4) the West Side Railway Company (or “Becker Line”) owned by Republican Washington Becker.[4] Because each company had its own fare system and obtained grants to operate where its political connections were strongest, the tangle of routes was uncoordinated and inefficient, causing long delays and discomfort for commuters.[5]

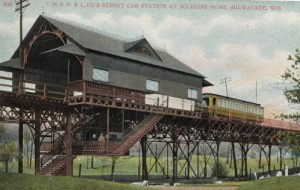

In 1890 nationally-renowned publisher and railroad tycoon Henry Villard took an interest in Milwaukee transit due to his own German origin and Milwaukee’s large German population and strong cultural influences. With the assistance of a young, well-spoken Henry C. Payne, Villard established the Milwaukee Street Railway Company and began to purchase, consolidate, and electrify most of the city’s horse-trolley lines. After a foray through bankruptcy, the company re-emerged in 1896 debt free as The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company (TMER&L Co.), a wholly-owned subsidiary of the North American Company; North American was an East Coast holding company that owned several other electrified streetcar systems in cities throughout the United States and Canada.[6]

The very first electrified trolley commenced service on Wells Street to much fanfare in April of 1890; while dubious at first, the public and press ultimately welcomed this major improvement in transit coordination and reliability, with the Milwaukee Daily Journal writing:

Now a person can make a date with the reasonable certainty of getting there within the time. But when the old mu-ly, mu-ly, mu-ly jog was in force, parents living on the East side would kiss their little ones with tender solicitude before starting out for the West, and vice versa, for like men who go out in ships, the length of their absence was uncertain, to say the least of it. Now you may leave the Northwestern station at any time you please, slide through the city like a greased pig through a lasso, touch the limit and return to your starting point in less than an hour.[7]

While welcoming the new jobs, streetcar workers were unhappy with both their wages and conditions of employment; average TMER&L Co. employees were unable to afford fares on the trolleys they drove and maintained. In May 1896, they collectively demanded that TMER&L Co. Vice President Payne make good on a previously promised one-cent per hour raise. When Payne refused, they went on strike, bolstered by a community-wide boycott; this unanimity of sentiment reflected community unhappiness with TMER&L Co. for failure to meet strikers’ demands. However, the strike broke down when the company brought in Chicago strike breakers and refused to relent; while a few workers were able to return to their jobs, most workers did not.[8]

In 1898, candidates from every party ran for mayor on the platform of municipal acquisition of the streetcar system. Voters elected David S. Rose, a Democrat who also made this pledge. Despite the apparent mandate for city ownership, in 1899 Rose entered secret talks with The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company to consolidate and extend the length of the company’s routes and the duration of its franchises. Following revelation of these talks, residents held citywide protest meetings and testified in animated city council meetings against such an agreement. Despite these objections, on January 2, 1900, Mayor Rose and a majority of the Common Council locked themselves and TMER&L Co. representatives inside the Common Council Chamber to bar protestors and signed a 35-year exclusive agreement with TMER&L Co. Several citizens’ groups filed unsuccessful complaints with state and federal courts to nullify this act.[9]

Between 1890, when many cities began electrifying their systems, and 1912, there was a 32-fold increase in railroad track mileage (“traction”) in the United States—from 1,262 to 41,022 miles of railway track. From 1890 to 1902 in the state of Wisconsin alone there was a tenfold increase in traction—from 45.5 miles to 446 miles of track.[10] As of 1908, Wisconsin’s streetcars carried approximately 300,000 passengers daily. By the late 1920s, interurban electric trains connected Milwaukee to Sheboygan, 58 miles north; “Waukesha Beach” (now Pewaukee Lake), 22 miles west; Burlington, 35 miles southwest; and Kenosha 40 miles south. These interurban routes were run by TMER&L Co. through its subsidiary, The Milwaukee Light Heat & Traction Co. (TMLH&T Co.), and served roughly 30,000 passengers every day.[11]

In 1905, Governor Robert La Follette, a Republican from the party’s Progressive wing, persuaded the Wisconsin legislature to pass a Railroad Act that gave him authority to appoint a three-man commission overseeing freight railroads in the state. In 1907 the legislature then extended this law to cover city streetcars, interurban electric rails, and other forms of transit, including those in Milwaukee. The law effectively removed any transit regulation authority from cities, placing oversight exclusively in the hands of the Railroad Commission. If the city of Milwaukee had owned the system, the city could have responded to citizen complaints in a timely fashion. Instead, the city attorney’s office acted as representative for Milwaukee residents, taking their concerns to state officials in Madison and, in this role, had much less power to meet their needs and shape city development.[12]

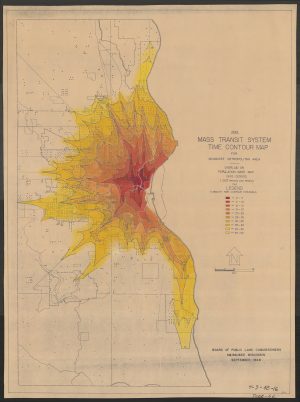

In 1924 Wisconsin passed a Home Rule constitutional amendment, granting Milwaukee and other Wisconsin cities more power to govern themselves. Mayor Daniel W. Hoan had been the amendment’s chief proponent since 1911, when he was Milwaukee City Attorney. After the amendment’s adoption Hoan hoped the city would finally have the authority to guide any future transit development in the growing metropolis. In 1926 the city therefore commissioned the nationally-esteemed engineering firm McClellan & Junkersfeld to conduct a comprehensive study of Milwaukee area transit. The resulting 1928 report proposed a carefully plotted network of semi-rapid transit lines, rapid transit lines, local service streetcars and buses, automobile parking facilities, and truck and rail freight routes. All together, these were envisioned to serve short- and long-distance commuters, commercial vendors, and manufacturers.[13]

Due to the increasing availability of automobiles and the expansion of safe roads in the 1920s, streetcar ridership slumped. Once automobiles were enclosed against the elements, travel in cars was more comfortable during inclement weather. These developments coincided with Mayor Hoan’s exploration of ways for the city to purchase the transit system. Although in retrospect the automobile’s dominance is unmistakable, Hoan’s continued interest in municipal ownership of streetcars was not entirely without merit; Milwaukee’s street railway service continued to expand through 1928, when it reached 131 miles of track, before declining rapidly to 105 miles during the Great Depression. Ridership persistently surged during heavy snowfalls; special snowplowing streetcars made rail travel possible when automobile street travel was not.[14] The city and TMER&L Co. were in the process of gathering funding to make some of the changes recommended by McClellan & Junkersfeld when the U.S. stock market crashed in 1929.

Subsequently, the U.S. Congress passed the Holding Company Act of 1935, which forced entities like North American—TMER&L Co.’s parent company—to divest themselves of municipal transit within a short period of time. The purported goal of this measure was to prevent potential speculation and monopoly collapses in cities throughout the United States, as happened with Chicago transit mogul Samuel Insull’s large streetcar, rail, and electricity investments in the 1920s. Consequently, in 1938 North American Co. divided the electric and transit services that had together operated as TMER&L Co.; however, this division only occurred on paper, with Milwaukee’s electric company (renamed WEPCO) continuing to own the transit company until after World War II, when the Securities and Exchange Commission saw through this ploy and ordered genuine divestment.[15]

In the meantime, facing dramatic losses during the Depression, TMER&L Co. tried to boost its revenue by using passenger rails for shipping purposes, competing with increased delivery truck traffic clogging downtown Milwaukee streets. At the same time, it sought and acquired the state Commission’s consent to transform track-bound lines into electrified, rubber-tired “trackless trolleys.” The company argued that these vehicles offered greater maneuverability for drivers and comfort for passengers, while reducing traffic congestion on mixed-use downtown business streets. This approach also allowed the company to avoid the costs of fixing rusty tracks. Replacing the old retrofitted streetcars with the newest Presidents’ Conference Committee electric streetcars that Chicago, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and other cities had adopted would have required too much short-term capital infusion to pay for newer tracks and the new rail cars, the company claimed. Significantly, a legal loophole at the time required the company to pay a fee for streetcar use of the streets but not for trackless trolleys. Additionally, the company had been incurring street repair costs whenever the city repaved its roads; it had to pay to repave the portion of the road between the tracks. If using rubber tires, it could avoid all of these costs. Despite protracted, vocal opposition by streetcar advocates, TMER&L Co. obtained Wisconsin Public Service Commission approval for these changes.[16]

Streetcar and trackless trolley ridership experienced a temporary upsurge during World War II due to the influx of industrial workers and movement of military troops. But the numbers fell precipitously after the war, once steel again became available for new cars. The federal government further fueled consumer automobile purchases by providing thirty-year Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration mortgages to returning veterans and their new families, who built homes in the suburbs. It also invested in the largest roads project in U.S. history, popularly known as the Federal Highway Act of 1956. The resulting federal, state, and local highway expansion facilitated long automobile commutes of suburbanites. In this climate, the transit company in Milwaukee replaced all streetcars with buses.[17]

In the post-war era, the still privately-owned metropolitan transit system as a whole was dying. Some local officials, business leaders, and commuters expressed concern that both rapid transit interurban and intra-city routes—whether rail or rubber-tired—might be shut down all together. In particular, commuters from Wauwatosa, the suburb immediately west of Milwaukee across the deep Menomonee River Valley, were concerned about the remaining interurban electric rail line, the “Speedrail.” The Wisconsin Public Service Commission held lengthy hearings contesting the closing of this line.[18]

The company presented a prospectus for sale to the city in 1947, but by this time Daniel Hoan (1916-1940) was no longer mayor. Because the city had neither the resources nor jurisdiction over the system’s entire geographic area and city leadership was in flux, the city initially declined to act on the offer. However, soon after taking office in 1948, Mayor Frank P. Zeidler approached officials from neighboring cities about collectively purchasing the transit system. Like officials in other jurisdictions, Zeidler and the Common Council feared National City Lines (NCL), backed by General Motors and other automobile industry giants, would purchase and promptly dismantle it; NCL’s acquisition and dismemberment of street rail systems for scrap metal in other cities was widely publicized. Zeidler and allies from Waukesha and West Allis drafted enabling legislation to establish a Metropolitan Transit Authority intended to allow Wisconsin cities to collectively purchase and run both intra- and intercity transit through regional partnerships. However, before this bill passed the state legislature in 1949, the drafters changed the language so that any authority created under the law would not have non-profit status. Such status would have protected any resulting regional transit entity from paying federal taxes and permitted it to sell bonds at higher rates; this non-profit status was integral to the success of any such transit authority.[19]

While the law’s strongest supporters were trying to get it amended to the language they had originally intended, a different outside company (not National City Lines) bought the west and southwestern lines of the interurban system, which became known as the Milwaukee Rapid Transit and Speedrail Company. Between the years 1948 and 1956, when the law was finally amended, the cooperative relationship between Zeidler and his local suburban allies broke down over the Oak Creek Law, which allowed vast unincorporated, township lands to incorporate as cities.[20] Without the tax money lost to the newly incorporated city of Oak Creek, and without neighbors willing to share in running a Metropolitan Transit Authority, the MTA idea was abandoned.[21]

Also, two major crashes of the Speedrail line in 1949 and 1950—the latter a fatal head-on collision—prompted the Public Service Commission to shut down all remaining routes, ending service between Milwaukee and Hales Corners and Milwaukee and Wauwatosa. The lines had already stopped running to Burlington and Waukesha before the crashes. Faced with expensive lawsuits, the company filed for bankruptcy. Despite all of these problems Mayor Zeidler continued to launch studies on MTA or city purchase of the system, but his efforts fell on deaf ears.[22]

By 1960, the Public Service Commission had allowed the Milwaukee & Suburban Transport Company to convert all of its streetcars and trackless trolleys to bus routes, the Rapid Transit and Speedrail Company had gone bankrupt, and transportation along all prior interurban routes was now provided by the Greyhound Corporation. In 1962 the federal government passed legislation that granted funding to local, government-owned rail transit authorities, but no one was talking about commuter rail at that point—with the exception of former Mayor Frank Zeidler and Attorney Bruno Bitker, a long-time rail advocate who had been the Speedrail’s bankruptcy trustee.[23]

In 1975, Milwaukee & Suburban Transport Co. (successor to TMER&L Co.), which ran the now exclusively bus-driven service, declared bankruptcy, blaming its financial troubles on the impossible demands of its now unionized workers. After the bankruptcy, Milwaukee County rather than the City of Milwaukee acquired the bus system.[24] Since that time, there have been several efforts at local, regional, and state levels to expand commuter options. In early 2011, after turning down $810 million in federal funds to build high speed rail, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker and the Republican majority legislature repealed a Regional Transit Authority Act that had passed in 2009, which would have allowed Milwaukee and its municipal peers to establish joint control over new transit efforts—similar to the MTA of 1949.[25]

The twenty-first century reality is that many Milwaukee-area commuters both live and work outside the central city’s limits. In fact, many people travel between counties within the greater Southeast Wisconsin area. However, no regional governing body coordinates transit within this larger area and each county controls its own bus system, with a patchwork of state and local entities controlling highway and road development and repair.

As of 2016 the Milwaukee County Transit System (MCTS) operates 415 buses offering service on 59 distinct routes and provides approximately 150,000 passenger trips per weekday during the school year. Through the U-PASS program, over 50,000 college students are eligible for unlimited rides. Almost half of the system’s riders are between the ages of 18 and 44. Riders access the bus service for a number of purposes, with 42 percent using it primarily for work commutes or job searches, 11 percent for shopping, 12 percent to attend school, 15 percent for medical appointments, and 6 percent for other reasons. Buses run both locally on city streets and as freeway flyers connecting “park and ride” lots to the city’s downtown district.[26] Although the county owns the buses, they are run by a private corporation, Milwaukee Transport Services, Inc., under a long-term contract with the county. Funding for the system derives from passengers and advertising (together 35 percent), the State of Wisconsin (43 percent), the federal government (11 percent), and county property taxes (about 11 percent), with the remaining half a percent coming from other state and federal sources. MCTS collects approximately $56.5 million annually from passengers and related sources like advertising.[27] As to interurban service, several private companies connect Milwaukee to nearby cities, including the Badger Bus between Milwaukee and Madison, Amtrak’s Hiawatha commuter rail service with seven daily round trips to Chicago, and Greyhound and Coach USA to cities nationwide.[28] In 2016 Milwaukee upgraded its Intermodal Station, facilitating transfer between the Amtrak Hiawatha line and Greyhound and MCTS buses.[29]

For several decades now, the city has explored the possibility of building a new, city-owned streetcar. Despite sustained opposition at the state level, including complaints filed with the Wisconsin Public Service Commission, Milwaukee is still on track to commence service on the initial route of a new city-owned streetcar in 2018. Opposition to the new system came from two separate spheres: a contingent of mostly conservative taxpayers who were unhappy with the system’s expense and inner city residents who resented that it would initially serve only the downtown and tourist areas. Extensions of the system to serve Bronzeville, the city’s historic black business district, and the new Bucks basketball arena are under consideration as well, pending additional funding.[30]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Zachary Schrag, “Urban Mass Transit in the United States,” EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. May 8, 2002, http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/schrag.mass.transit.us, last accessed October 1, 2016, now available at http://eh.net/encyclopedia/urban-mass-transit-in-the-united-states/.

- ^ Before the County acquired it, the City of Milwaukee attempted on numerous occasions to purchase the transit system. As far back as the 1890s, the city sought ownership of its streetcars, and at several junctures attempted to establish a multi-modal system that would reduce congestion through dedicated rapid and semi-rapid routes, to coordinate housing and business zoning with future transit planning, to carefully plan parking facilities and limit street parking, and to regularly consult with large employers and commuters regarding concerns and preferences. Karen W. Moore, “Missed Connections: The ‘Progressive’ Derailment of Public Transit in Metropolitan Milwaukee during the Electric Streetcar Era (1890-1960)” (Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2011), 1-8.

- ^ Clay McShane, Technology and Reform: Street Railways and the Growth of Milwaukee, 1887-1900 (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1974), 4; Moore, “Missed Connections,” 4-6, 47-57.

- ^ Moore, “Missed Connections,” 65.

- ^ Kenneth Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2008), 33; Moore, “Missed Connections,” 5-6; “History of Rapid Transit in Milwaukee,” Street Railway Review (September, 1893): 530, reprinted in Elijah Ellsworth Brownell, Electrolysis from an Engineer’s Standpoint (Chicago, IL: Self-published, 1905), 90.

- ^ McShane, Technology and Reform, 23-25, 44; Moore, “Missed Connections,” 6. Regarding the bankruptcy, it should be noted that most of the key creditors that had their claims thrown out were local horse-streetcar owners/businessmen who had been bought out by Villard.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee, the History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 370, quoting Milwaukee Daily Journal, September 12, 1891.

- ^ Donald Mueller, “A Milwaukee History of Street Railway Transportation (Which Can Be Made Supplementary to That Appearing in Trolley Sparks, Bulletin 97),” unpublished paper, Donald Mueller Collection, Mss 92, Box 6 Folder 18, Golda Meir Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; “The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company: ‘Memories,’ 1966” by William F. Nedden, January 11, 1966), in the same collection.

- ^ Moore, “Missed Connections,” 85-86.

- ^ Fred L. Holmes, The Regulation of Railroads and Public Utilities (New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co., 1915), 159-160; the charter for the Appleton, Wisconsin system indicates its establishment on January 1, 1886. Wisconsin’s system of freight railroads had also been growing exponentially. “By 1860 Wisconsin had 905 miles of track; 2,950 miles by 1880 and 6,592 miles by 1900.” Joseph A. Ranney, “Imperia in Imperiis: Law and Railroads in Wisconsin, 1847-1910,” in “Wisconsin’s Legal History: Part III,” Wisconsin Lawyer, http://www.wisbar.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Wisconsin_s_legal_history&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=35840#19, accessed December 27, 2010.

- ^ “North American Company,” Poor’s Manual-Miscellaneous Industrial Corporations 33 (1900).

- ^ “North American Company,” 109-130. To this day the Railroad Commission, later renamed the Public Service Commission, remains the sole non-federal government entity to regulate transit in the Milwaukee region. This is despite the city’s repeated attempts to acquire ownership and/or control of the system; in 1921 a countywide referendum vote asked voters whether the city should enter so-called Service-at-Cost arrangement whereby city government would have greater oversight of TMER&L Co.’s activities and provide a path to eventual city ownership. The referendum lost by a two to one margin; its wording was complicated, and a growing anti-tax contingency spread rumors that the taxpayers would be stuck paying for the system. Further, the Service-at-Cost plan was not an outright purchase; municipal ownership advocates felt double-crossed by Mayor Hoan, who himself had only recently realized that an outright purchase would be impossible without a Home Rule law granting the city greater powers. “North American Company,” 192-197.

- ^ Moore, “Missed Connections,” 197-214.

- ^ “Miles of Rails Are Deserted: Milwaukee Makes Rapid Progress in Modernizing Its Transportation; Further Use of Autos Planned,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 30, 1938, Rapid Transit Clippings File, Milwaukee Public Library (hereafter MPL).

- ^ “Miles of Rails Are Deserted,” 313-314.

- ^ John Gurda, Path of a Pioneer: A Centennial History of the Wisconsin Electric Power Company (Milwaukee: Wisconsin Energy Corp., 1996), 150-153; Moore, “Missed Connections,” 225-226, 300-313. The Commission allowed the company to unfairly compare the often fifty-year old flat-wheeled, rusting streetcars to brand new trackless trolleys, refusing to discuss the latest rail-car models available—called President’s Commission Cars (PCCs).

- ^ Moore, “Missed Connections,” 6, 223-226; “Miles of Rails Are Deserted”; “History of the Interstate Highway System,” Federal Highway Administration website, U.S. Dept. of Transportation, accessed June 21, 2011; “Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956: Creating the Interstate System,” http://www.nationalatlas.gov/articles/transportation/a_highway.html#top, accessed June 21, 2011.

- ^ Moore, “Missed Connections,” 324-330.

- ^ Moore, “Missed Connections,” 331-342.

- ^ Joel Rast, “Annexation Policy in Milwaukee: An Historical Institutionalist Approach,” Polity 39, no. 1 (Jan. 2007): 55-78. The Oak Creek Law ironically passed due to enabling provisions in the Home Rule Amendment that Mayor Hoan had championed. The law took substantial industrial land—representing a potentially lucrative tax base—away from Milwaukee, which had been trying to acquire it for many years.

- ^ During this same period Wisconsin Governor Kohler established a committee to study the future of Milwaukee area transit, appointing the head of the state highway commission as committee chair and individuals from Green Bay and other remote locations as committee members. This further reduced Mayor Zeidler’s influence over transit in the region. “Kohler Gets Plan to Save Mass Transit; 5-Man Commission Submits Report,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 31, 1954, accessed June 24, 2011.

- ^ Joseph M. Canfield, TM: The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company (Chicago, IL: Central Electric Railfans Association, Inc., Bulletin 112, 1972), 364-65; “Dead, Injured ‘Piled Six High,’” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 3, 1950, accessed June 27, 2011; “Milwaukee Rapid Transit & Speedrail Company, 1950-1970,” MSS #048, Box 1, Folder 2, “In the Matter of Milwaukee Rapid Transit and Speedrail Co., Debtor,” kn Proceedings for the Reorganization of a Corporation under Chapter X of the Bankruptcy Act., No. 27508, Trustee’s Report on Stockholder’s Offer, November 30, 1951, pp. 2-3, MPL Local History Collection; Virgil H. Hurless, City Comptroller, “Report of the Office of the City Comptroller Relative to the Offer of the Milwaukee Electric Railway & Transport Company to Sell Its Passenger Transportation Properties to the City of Milwaukee” (Common Council File No. 51-643), City of Milwaukee Legislative Reference Bureau, 1951.

- ^ Bruno V. Bitker, Trustee for the Milwaukee Rapid Transit and Speedrail Company, “Trustee’s Report on Stockholder’s Offer in Proceedings for the Reorganization Of a Corp. under Ch. X of Bankruptcy, No. 27508,” November 30, 1951, Bitker Papers, Mss #048, Local History Manuscript Collection, Box 1, folder 16, MPL; “Cities Offered Help in Commuter Transit Crises,” New York Times, April 6, 1962, 19; preamble to Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964, 49 USC §5301(b).

- ^ Moore, “Missed Connections,” 7, 335.

- ^ Patrick Marley and Don Walker, “State Panel Repeals Regional Transit Group,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 3, 2011.

- ^ Milwaukee County Transit System website, last accessed April 24, 2016.

- ^ Milwaukee County Transit System website, last accessed April 24, 2016.

- ^ See Amtrak’s Hiawatha webpage, last accessed April 16, 2016. If mass transit includes more than daily commutes, then other passenger options include air service via the County-owned Mitchell International Airport and private jet service from several smaller fields in the Milwaukee and four-county area. Amtrak’s Empire Builder train connects Milwaukee to western parts of Wisconsin and Minneapolis-St. Paul, continuing west through several northern states until it splits into two routes at Spokane, Washington, ending in Portland and Seattle.

- ^ “$22 Million Terminal Reconstruction Project Complete at Milwaukee Intermodal Station,” Fox6Now, June 22, 2016, last accessed August 14, 2017.

- ^ The Milwaukee Streetcar website, accessed March 3, 2016; Sean Ryan, “Is Bronzeville the Next Stop for the Milwaukee Streetcar?,” Milwaukee Business Journal, April 29, 2016; Jeramey Jannene, “Council Okays Streetcar to Bucks Arena,” Urban Milwaukee, July 6, 2016, accessed November 5, 2016.

For Further Reading

Barrett, Paul. The Automobile and Urban Transit: The Formation of Public Policy in Chicago, 1900-1930. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1983.

Caine, Stanley P. The Myth of a Progressive Reform: Railroad Regulation in Wisconsin, 1903-1910. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1970.

Canfield, Joseph M. TM: The Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company. Chicago, IL: Central Electric Railfans Association, Inc., Bulletin 112, 1972.

Casey, Jr., James J. Mayor Frank P. Zeidler: Transportation Development in Post-War Milwaukee. Kansas City, MO: APWA Press, 2006.

Cheape, Charles. Moving the Masses: Urban Public Transportation in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, 1880-1912. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Commons, John R. “The Wisconsin Public-Utilities Law,” Review of Reviews and World’s Work: An International Magazine 36, August 1907.

Gurda, John. Path of a Pioneer: A Centennial History of the Wisconsin Electric Power Company. Milwaukee: Wisconsin Energy Corp., 1996.

Hoan, Daniel W. The Failure of Regulation. Milwaukee: The Socialist Party of the United States, 1914.

Mayer, Harold M. “By Water, Land, and Air: Transportation for Milwaukee County,” in Ralph M. Aderman, ed. Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987.

McCarthy, Charles. The Wisconsin Idea. New York, NY: The MacMillan Company, 1912.

McClellan & Junkersfeld, Inc. Report on Transportation in the Milwaukee Metropolitan District to the Transportation Survey Committee of Milwaukee, Vol. I. New York, NY: McClellan & Junkersfeld, Inc., 1928.

McShane, Clay. Technology and Reform: Street Railways and the Growth of Milwaukee, 1887-1900. Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1974.

Moore, Karen W. “Missed Connections: The ‘Progressive’ Derailment of Public Transit in Metropolitan Milwaukee during the Electric Streetcar Era (1890-1960).” Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2011.

“North American Company.” Poor’s Manual-Miscellaneous Industrial Corporations 33 (1900).

The North American Company: An Account of the Part of the North American Company in the Development of the Public Utility Industry and the Consequent Growth of Its Properties, Its Business and Its Earnings. New York, NY: Self-Published, 1926.

Norton, Peter D. Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008.

Simon, Roger D. The City-Building Process: Housing and Services in New Milwaukee Neighborhoods, 1880-1910. Revised ed. Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society, 1996.

Stephenson, Kimberly. “Can Government Mandate Citizens’ Voice?: A Case Study in Transportation Policy.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2010.

Teaford, Jon C. “State Administrative Agencies and the Cities: 1890-1920.” The American Journal of Legal History 25, no. 3 (July 1981): 225-248.

Wilcox, Delos F. Analysis of the Electric Railway Problem Prepared for the Federal Electric Railways Commission. New York, NY: Self-Published, 1921.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.