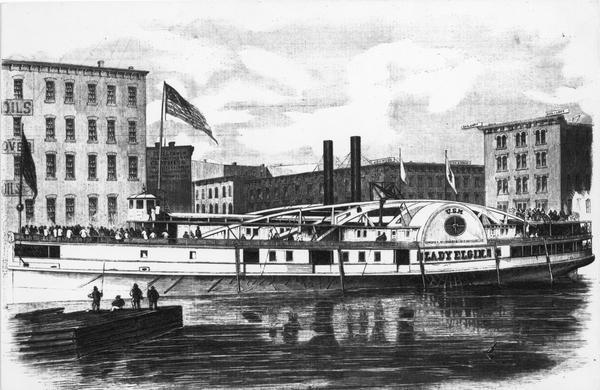

In one of the worst maritime disasters in the history of the Great Lakes, the steamship Lady Elgin sank off the coast of northern Illinois during the early hours of September 8, 1860. The ship left Milwaukee late on September 6 bound for a political rally in Chicago with approximately four hundred passengers on board, including members of Milwaukee’s “Union Guards” militia unit. Returning amid heavy rain and high winds, the Lady Elgin was struck by the lumber schooner Augusta shortly after two o’clock in the morning and sank within half an hour, leaving fewer than one hundred survivors. Of those that perished, the majority were Irish residents from Milwaukee’s Third Ward.[1]

For Further Reading

Gurda, John. The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999.

Hilton, George Woodman. Lake Michigan Passenger Steamers. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002.

St. Mane, Ted. Lost Passenger Steamships of Lake Michigan. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2010.

Explore More [+]

Understory

Counting the Victims of the Lady Elgin Disaster

In the days after the sinking of the Lady Elgin there was chaos and confusion in the early reporting of victim names and victim count, similar to the experience following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. But in the weeks following both disasters the names and numbers of victims and survivors came into focus. However, as the years passed, reports of the number of people on the Lady Elgin burgeoned.

At the time of the disaster, the captain of the Lady Elgin estimated about 400 people were aboard the vessel.[1] The 1st mate, George Davis, estimated that there were between three and four hundred passengers and forty-eight crew members.[2] The official inquest, based on the testimony of survivors as well as information provided by families and friends of passengers, determined that there were about 400 on board and that about 300 perished.[3] These figures were commonly accepted at the time and are reflected in the chorus of a popular song, “Lost on the Lady Elgin” by Henry Clay Work:

Lost on the Lady Elgin, sleeping to wake no more,

Number’d in that three hundred, who failed to reach the shore.

Modern day research and analysis of many records regarding those involved has led to evidence for 396 passengers and crew, 302 of them victims.[4]

A generation after the disaster, an 1892 Milwaukee Sentinel article reported that there were 500-600 passengers on the ship.[5] A historical marker dated 1996, located in the Historic Third Ward states, “Aboard the ship were more than 500 Union Guard supporters.”[6] (With crew and other passengers, this would put the number on board at over 600 people.) A shipwreck website claims, “Further, it is estimated that at least 700 passengers were on the Lady Elgin when she was lost.”[7]

The reason for these higher estimates many years after the disaster were the lists of passengers printed in newspapers in the days after the sinking. Milwaukee and Chicago, the most affected cities, printed the most about the disaster. We have at least ten different newspapers from these places available to us today, and they printed dozens of lists. Additionally, every Great Lakes’ city’s newspapers printed lists, as did Wisconsin newspapers and those throughout the country, including the New York Times.

Virtually every newspaper list included factual and spelling errors. There were people listed as being passengers, but who were not: like Gurdon Hubbard, the owner of the Lady Elgin, and Philip Best, leader of Milwaukee’s recovery operations. Many names were misspelled. Thomas Shea, a survivor, had his surname misspelled in newspaper lists as Shay and Chase, and Philip Aylward’s last name was printed as Elywood, Elwood, Elward, Elmore, and Ellsworth.

A week after the accident, survivor Ed Mellon wrote in a letter to his brother and sister: “the newspapers and lists of the lost were very imperfect. In some newspapers they had me lost and saved in the same paper.”[8] Mellon’s name was also misspelled in newspapers as Mallen and Mullen. In The Lady Elgin Disaster, a book written in 1928, there are over 525 names of passengers listed in the appendix. The author cautions though: “There is great difficulty in obtaining the correct names of either the saved or the lost, as newspaper men misspelled many names.”[9]

The current day researcher can easily be misled about the number of people on the Lady Elgin if the names reported in newspaper lists of the time are simply accumulated without further analysis.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “Fred Snyder’s Statement,” Daily Wisconsin, September 10, 1860, 1.

- ^ “First Mate, George Davis’ Statement,” Chicago Daily Journal, September 15, 1860, 1.

- ^ Journal of Board of Supervising Inspectors, National Archives Record Group 41, vol. 1, p. 42-43.

- ^ Valerie Van Heest, Lost on the Lady Elgin (Holland, MI: In-Depth Editions, 2010), 39.

- ^ “Loss of the Lady Elgin,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 4, 1892, 1.

- ^ “Sinking of the Lady Elgin,” Wisconsin Official Marker, Erected 1996, N. Water and E. Erie streets.

- ^ Brendon Baillod, The Wreck of the Steamer Lady Elgin, “Lady Elgin Passengers—September 6, 1860,” last accessed May 22, 2017

- ^ Van Heest, Lost on the Lady Elgin, 95.

- ^ Charles Scanlon, The Lady Elgin Disaster (Milwaukee: Cannon Printing Co.?, 1928), 96.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.