Milwaukee’s history is refracted through its built environment. The style, construction, and decorations of buildings tell us about the priorities of the builders and how they were used—a direct reflection of the lives and work of their occupants. Some nineteenth-century buildings survive in twenty-first century Milwaukee. People who walk, ride, or drive by them, or who enter them, can get a glimpse of what Milwaukee used to be like. Their continued existence allows viewers to see Milwaukee’s past in the present. As construction methods and building codes have outmoded older buildings, historic preservationists have saved some, while others have been remodeled for new uses. Still other buildings that once served important local functions are now gone. They deteriorated beyond repair or their functions were no longer valuable, and they were torn down. Like still extant buildings, the ghosts of missing buildings also serve as a window into the city’s past. The stories of their disappearances from the landscape tell us about Milwaukee’s changing economic environment.

The Downtown is a particularly good venue for considering the transformations of the city’s built environment. The Downtown has been thoroughly transformed from its humble beginnings of simple wilderness cabins in the 1830s to the new skyscrapers of the 21st century. A variety of buildings rose in between these periods; some remain to this day and others have lingered for shorter times. Older buildings have only occasionally survived the conflict between historic preservation and economic needs.

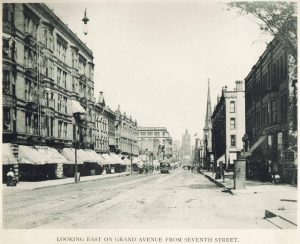

As with evolving styles of architecture, the city changed in phases. The first phase saw the linking of the rival settlements of Solomon Juneau and Byron Kilbourn on the east and west banks of the Milwaukee River. Today, Wisconsin Avenue is Milwaukee’s main street. East of the river it was always called Wisconsin Street. But west of the river, it was first called Spring Street. In 1876, the street became Grand Avenue. And it was finally linked with the East Side and called West Wisconsin Avenue in 1926.[1] The Milwaukee River and the streets paralleling it were the center of the city’s commerce and trade during its early history. Around 1870, as the city increased in population and territory, this area lost its monopoly on commercial activity. The East and West sides of the Avenue began as merely residential streets. But the thoroughfare gained enough importance that dry goods merchant Timothy A. Chapman erected his first store on the southeast corner of Wisconsin Street and Milwaukee Street in 1872[2]. The building lasted until a fire demolished the store in late 1884. Chapman lost no time rebuilding a store that was grander and more substantial than its predecessor. It was finished in 1885. The department store grew in prominence and size through the early part of the twentieth century. The advent of freeways and shopping malls in the 1960s undermined the importance of Downtown as a shopping destination, and Chapman’s finally closed its doors for good in 1981. The once magnificent “Palace of Trade” was torn down the following year to make room for a new thirty-story office tower, thus reflecting how the Downtown was changing from a center of commercial goods to a provider of services.

At the east end of Wisconsin Avenue, in the mid-1870s the Chicago and North Western Railway extended a rail line from the South Side. This line eventually connected with the Wisconsin cities of Fond du Lac and Green Bay. This development coincided with the beginning of the period in which Wisconsin Avenue began to grow into an important commercial strip. Initially, the railroad added a stop on the south side of the street at Marshall Street. The station was a modest building converted from a former school house.[3] It remained until a large ornate depot building was constructed at the same location in 1889 after plans by Chicago architect Charles Sumner Frost. This station was built in the popular Richardsonian Romanesque style, with a dark red pressed brick and a clock tower 234 feet high and ringed with the heads of gargoyles. The waiting room was a cavernous hall with a fireplace at the southern end to warm passengers on a winter’s day.

The railway station functioned as a main entry point into the city for visitors from 1889 until it closed in 1966. Generations of Milwaukeeans had their first glimpse of the city upon leaving the station. Nearby hotels and sales offices flourished from that proximity. After its closing, ownership of the old depot was transferred to Milwaukee County government. It remained vacant until a decision could be made on its future. A preservation group, Land Ethics, Incorporated (now Historic Milwaukee, Inc.), attempted to find ways to preserve the old depot but ultimately could not get enough interest to save the building.[4] By April 1968 demolition plans were underway, and it was torn down. The site was used as a surface parking lot for many years until the county’s O’Donnell parking structure was built in 1989 as part of the William F. O’Donnell Park. The closing of the depot and the removal of railroad facilities along the lakefront freed up land for recreation purposes and allowed the transformation of the area into the cultural treasure it is today, with the Milwaukee Art Museum, Discovery World, and the Betty Brinn Children’s Museum all nearby.

In the western portion of the Downtown, the erection of a skyscraper by Captain Frederick Pabst symbolized Milwaukee’s passage into the modern period. The earliest European settlement in Milwaukee is marked by a plaque on the west side of the building at the northwest corner of Water and Wisconsin. Originally a simple log home and trading post built by Antoine LeClaire, this was the starting point of the city. Ludington’s brick block replaced the cabin in 1851. By the early 1890s, Captain Frederick Pabst chose the location to build a skyscraper as a symbol of his growing brewing empire. The Pabst building was fourteen stories tall—about 235 feet from the sidewalk to the top of the copper tower. It was constructed of brown brick, heavily ornamented with terra cotta, and featured a large, curved, stone main archway. The central tower was topped by a copper-covered crown with four large clock faces. The architect of this tower, Solon S. Beman of Chicago, was chosen from several competitors to design a masterpiece of Romanesque Revival style. He succeeded in making an iconic building with an ideal setting on the river that was the most widely known picture postcard view of the city.

The decline of the Pabst building was slow. In the late 1940s, due to structural deterioration, the copper towers were removed, and the building’s rooflines were squared off. The changes were meant to make it appear contemporary, but the elaborate details of the carvings and ornamental terra cotta from an earlier age could not be hidden. The building remained standing until 1981, when plans for a newer office tower were being finalized. As it was being demolished, a last-ditch effort was made to save the ornate stone archway so it could be used as a monument elsewhere. With the rest of the building demolished, the archway stood alone. An attempt to push it over on its side failed; the damage was too great, so its pieces were taken to a landfill. The property sat vacant until 1988, when the current 100 East Wisconsin building was constructed with a modern interpretation of the old Pabst building. The new building provides offices built to current standards but nods to its nineteenth-century predecessor.

Traveling west of the river on Wisconsin Avenue is to witness the pinnacle of development that took place in the 1910s and 1920s, before the stock market crash put a forty-year halt to changes in the streetscape. From the Milwaukee River to Eighth Street, nearly all the existing buildings were built in those first twenty years of the new century. Only a few were built in the 1960s, while others like the Shops of Grand Avenue, the Library Hill apartments, and the Wisconsin Center were built more recently. Some older buildings were completely modernized, including the Purdue University Global (formerly Kaplan University) building at the southwest corner of 2nd and Wisconsin and the Hampton Inn and Suites on the northeast corner of the same intersection. Beginning in the first few decades of the twentieth century this stretch of the Avenue was the place to go for shopping and entertainment in Milwaukee. Movie theaters and department stores drew large crowds day and night, and major hotels kept people there even longer.

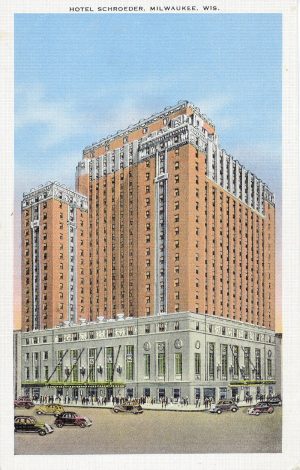

Only one major hotel, now known as the Hilton at the southwest corner of Fifth Street and Wisconsin Avenue, remains from that early era. It was opened as the Hotel Schroeder in February 1928. Another major hotel, built a year earlier, was the Hotel Randolph on the southwest corner of Fourth and Wisconsin Avenue. The Randolph was an elegant, twelve-story, 150-room, red brick hotel built for jeweler Archie Tegtmeyer. Herbert W. Tullgren designed the building using bands of ornate terra cotta to create a signature style found in many of his designs. In 1932, Tegtmeyer lost the building after defaulting on the payments—a victim of the stock market crash of 1929.

The Randolph subsequently went through several owners. By the 1950s it was renting long-term rooms to low-income residents at the price of $14 per week. It continued to decline along with the surrounding Westown neighborhood until the 1980s, when the City took steps to clear out blight with an urban renewal program. The City of Milwaukee purchased the property in June 1984. The following year the former hotel was demolished in a controlled detonation with the hope that a vacant lot would be more attractive to prospective developers. Since that time it has remained as a surface parking lot. A few proposals have been made to build hotels on the entire half block property, but none has progressed past the planning stage.

During the 1880s large apartment blocks were built in the 600 and 700 blocks of West Wisconsin Avenue. These were for residents who wanted to live in proximity to the conveniences of city life. Apartment buildings were an innovation in Milwaukee’s landscape, with one of the first built in 1882 at 603 West Wisconsin Avenue. Six years later the Norman Apartments were built nearly across the street. The Norman was trendy for its time, a five story brick building with twenty-six apartments on the upper floors and space for stores on the lower level. By the 1920s this was a booming area of downtown.

In the mid-twentieth century, however, the downtown began to stagnate. A 1953 newspaper article tried to paint a rosy picture but added a foreshadowing of the future: “Downtown Milwaukee could be given a tremendous lift if large real estate owners could be induced to do a full-scale modernization job, but…most of them are content to live comfortably on the income of their real estate as it is today.”[5] At the end of the decade, in 1959, the Milwaukee Journal wrote a scathing series of articles about “Our Shabby Downtown”[6] detailing the myriad of problems with decay in downtown’s buildings.

The Norman was singled out in “Our Shabby Downtown” for its vacant storefronts, typical of the problems of other older buildings. In the 1970s, there was an adult video and book store located next door, as well as active prostitution on the block. Apartment rentals in downtown were becoming cheaper, with units usually rented to older retired people or college students from Marquette University. A fatal fire in January 1991 destroyed the building, taking the lives of four residents. The corner where the building stood was cleared and replaced with a parking lot later that year and has remained the same since then.

One of the more recent losses to the Milwaukee landscape was a lone holdout of the freeway construction era of the late 1960s. The Sydney Hih building (Nicholas Senn Block) along with three other smaller buildings on the northwest corner of Third and Juneau survived the construction of the Park East Freeway in the early 1970s. The four story corner of the building complex was originally built by surgeon Dr. Nicholas Senn as a medical office building for himself and others. It later served as the offices of the West Side Bank, later Continental Bank & Trust, until 1967. Realtor Sydney Eisenberg purchased the vacant property in 1971 and christened it Sydney Hih. It became a haven for counterculture musicians and artists through the 1970s. With a multicolored checkerboard pattern of blues, reds, and greens painted on all its exterior walls, it became a landmark of a different kind. The basement club called The Unicorn was a center for eclectic punk rock acts.[7]

With the start of the 1980s a cultural shift led to more vacancies, and a few minor fires took their toll on the Sydney Hih building. The downward spiral continued until 2000 when it was closed down and the owners attempted to sell the entire property. The City finally bought the building in 2011 hoping to sell it along with the now vacant land where the Park East Freeway once lay. The following year, the Common Council chose to demolish the building against the wishes of a large number of historic preservationists.[8]

All of Milwaukee’s buildings have an impact on their surroundings. They help to transform and provide an identity to the neighborhood. In Milwaukee, this was especially true of much of the construction that occurred prior to the stock market crash of 1929. The city is dotted with low-rise buildings that enabled small businesses to co-exist in the Downtown alongside large department stores. The major demolitions of old buildings in the 1960s and 1970s that were intended to cure blight also made it more difficult to fit new buildings into a blank streetscape without stability or context. As developers are beginning to realize again with the latest rebirth of Downtown, a vibrant and self-sustaining city needs to have a balance of uses such as tourism, entertainment, commerce, and residences. Each use sustains the other.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “Milwaukee of Old Knew Many Roads, Few the Same,” Milwaukee Journal, September 19, 1951.

- ^ “Great Retail Center—A History of Grand Avenue and Wisconsin Street,” Milwaukee Sentinel, Sunday, March 29, 1896.

- ^ “New Depot Plans—The Passenger Station of the Northwestern,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 25, 1888.

- ^ “End of Line in Sight for Towering Depot,” Milwaukee Journal, February 2, 1968.

- ^ William A. Norris, “Downtown Found Hale and Hearty,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 10, 1953, accessed September 17, 2018.

- ^ “Our Shabby Downtown,” Milwaukee Journal, May 21-27, 1959.

- ^ Nicholas Senn Building Historical Designation Study Report, City of Milwaukee, February 2009.

- ^ “The Life and Death of Sydney Hih,” OnMilwaukee.com, December 26, 2016, last accessed September 23, 2017.

For Further Reading

Marti, Yance. Missing Milwaukee: The Lost Buildings of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee, Inc., 2011.

Swanson, Carl A. Lost Milwaukee. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2018.

See Also

Explore More [+]

Understory

Discovering Hidden History: The Case of the Missing Baby Hammocks

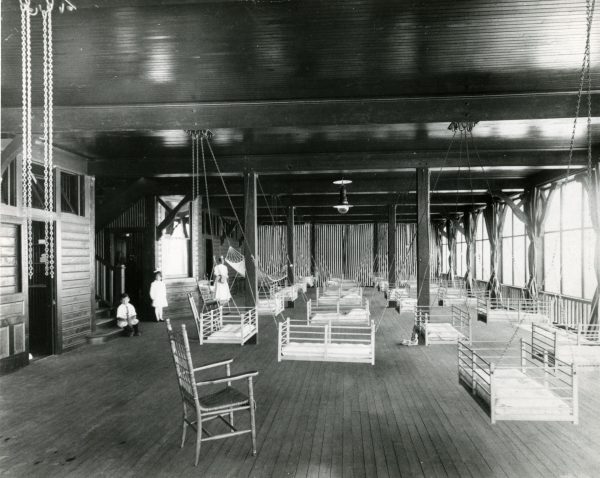

Sometimes something comes across your path and even though it is fascinating, there either isn’t time to study it as deeply or you don’t have a clue where to start. For me, the missing “baby hammocks” fell in to both categories. I was fortunate enough to work with a private collector who wanted to share everything she knew about Milwaukee, especially Lake Park, with me. As I collected images from her postcard collection, she shared mysterious photos that probably would have gone undiscovered in the Milwaukee Public Library Archives indefinitely. The pictures showed a beautiful wooden building with women in turn of the century clothing on the porch and what looked to be like cribs, on chains, suspended from the ceiling. I couldn’t help but wonder what was going on here. The only clues were a label on the picture “Babies Pavilion South East View” and what was obviously the water tower on North Ave in the background. The big questions were: what was this “babies pavilion” used for and where did it go?

Sometimes something comes across your path and even though it is fascinating, there either isn’t time to study it as deeply or you don’t have a clue where to start. For me, the missing “baby hammocks” fell in to both categories. I was fortunate enough to work with a private collector who wanted to share everything she knew about Milwaukee, especially Lake Park, with me. As I collected images from her postcard collection, she shared mysterious photos that probably would have gone undiscovered in the Milwaukee Public Library Archives indefinitely. The pictures showed a beautiful wooden building with women in turn of the century clothing on the porch and what looked to be like cribs, on chains, suspended from the ceiling. I couldn’t help but wonder what was going on here. The only clues were a label on the picture “Babies Pavilion South East View” and what was obviously the water tower on North Ave in the background. The big questions were: what was this “babies pavilion” used for and where did it go?

My first instinct was it had to be part of Columbia Hospital or St. Mary’s Nursing School, but I was too bogged down with postcard collections and getting my school work done to give what we came to call “baby hammocks” enough attention. I had to put the project on a back burner for a while, but it nagged at me to not know. I decided that during spring break, I would do some digging in my spare time and see what I could turn up. After talking over some preliminary research ideas, Amanda Seligman suggested I look at the Sanborn maps in the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee American Geographical Society (AGS) Library.[1] These maps were used for fire insurance and showed all the buildings in the area. Of course, there was no building in the approximate area I believed the building to have been. Back to the drawing board. I racked my brain for a few days while. Frustrated, I found myself back in Amanda’s office, feeling defeated. I sat there talking it out with her and blindly staring at her shelf of books on Milwaukee history, accusing her of knowing the answers to everything but not telling me, instead making me work for it. All of a sudden she remembered she had a book on public health in Wisconsin.[2] After checking the index for “babies’ hammocks” (a very unsuccessful method that I had already discovered) we checked under “pavilion,” and there it was. Milwaukee Infant’s Fresh Air Pavilion. Now that I had the correct name, I could move on with my research!

After a trip back to AGS Library to double check my original research, I was off to the Milwaukee Public Library Archives, home to the original pictures. Unfortunately, I was unable to find even the original pictures. I put in a request with the archivist on duty to see all the pictures of Lake Park before 1960 and made an appointment to come back in a few days. To my surprise, when I got there, she had not only been able to turn up the original photos, but found an article in the Milwaukee Journal from 1974. I was on the right trail. After spending some time in microfilm I was able to uncover a few more articles that mentioned the pavilion. As it turns out the Pavilion was used as part of the Milwaukee Infants Hospital for children suffering with tuberculosis. The popular belief at the time was fresh air would cure many breathing difficulties, including TB. By allowing the children to have a safe place free of charge, more children would survive childhood illness. The exact date it was built has yet to be determined but it was sometime between 1894 and 1914.

I have yet to find out why it closed, or what happened to the beautiful building. I was able to figure out almost exactly where the building stood, thanks to a very distinctive patio in the background of one of the pictures that still stands today. My next step will be to head to the Milwaukee Health Department Archives to see what I can turn up with the new clues I have. For instance, I know the pavilion was originally run by the Fortnightly Club, but there is no mention of it in their archives. I was able to find articles in medical journals that mention Dr. James Gurney Taylor, who at one time ran the Pavilion as part of the Infants Hospital. Now, I just have to find the time.[3]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ See, for example, Milwaukee 1894, vol. 1, key, from Insurance maps of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, published by the Sanborn-Perris Map Co. Limited, 1894, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Library Digital Collections website, last accessed August 24, 2017.

- ^ Judith Walzer Leavitt, The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform: Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982.

- ^ The author of this piece did find the time, as a master’s student at George Mason University. See Danielle Marie Eyre, Finding Fresh Air: The Lost History of Milwaukee’s Fresh Air Infants Pavilion, http://barelyahistorian.com/babyhammocks/, last accessed August 24, 2017.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.