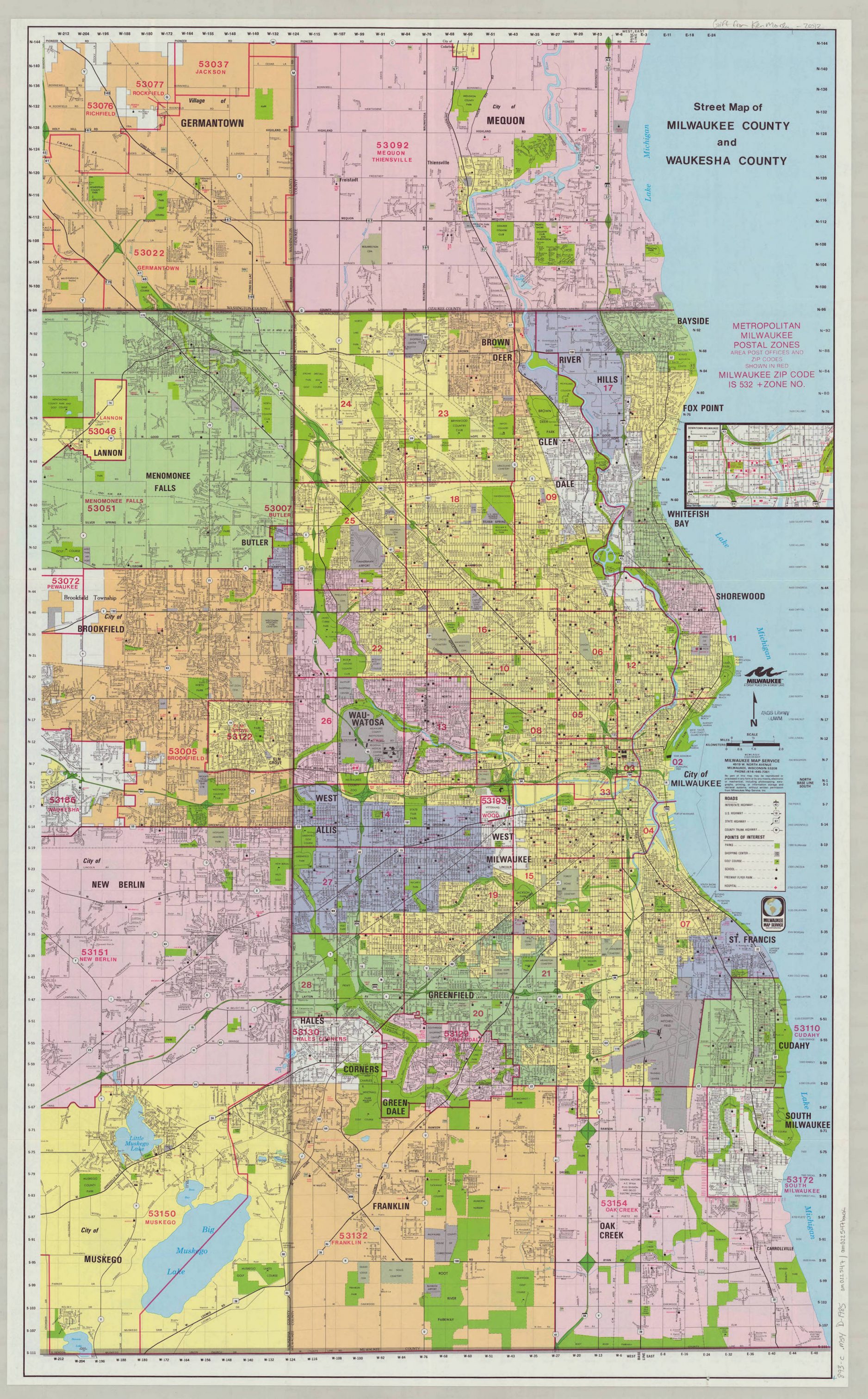

“Metropolitanization” can reference a perception, a behavior, or a process. As one moves north, south, or west from the central business district (CBD) of Milwaukee, a seemingly endless landscape of shopping malls and housing districts provides an “urban” definition to what we are seeing, until one reaches less developed areas in Ozaukee, Racine, and western Waukesha counties. Yet, without the aid of attendant signage, a traveler really has little idea of the political jurisdictions through which one has just passed (whether these be cities, villages, towns, counties, or school districts). Roadways may widen or narrow, and terrain may vary in undulation, but the self-imposed political boundaries that often separate residents are rendered meaningless. This is the visual reality of metropolitanization.

An early application of “metropolitan” arose in the post-Civil War era when Milwaukee’s mayor heralded the “decidedly metropolitan appearance” of Wisconsin’s largest city. He admonished citizens in 1868 to leave behind previous notions of village life and embrace the refinements of a mature metropolis. After all, more than a decade had passed since the city considered it necessary to pass ordinances to “restrain Horses, Cattle, Sheep, Goats, Dogs, Mules, Jackasses, and other Animals and Fowls, from running at large.” Instead streetcar lines, municipal waterworks, high schools, professional public safety departments, and a necklace of parks were fast becoming standard features of this thoroughly modern city.[1]

To become fully operational, this metropolitan character of greater Milwaukee had to be institutionalized through systems that united rather than divided. Plank roads, followed in short order by railroads, connected farmers from across Milwaukee and neighboring counties with the area’s harbor through which international commerce was tended, with leather factories for the processing of cow hides, and with its population center hungry for daily foodstuffs. These roadways and railroads promoted economic unity while, incidentally, facilitating population disbursement. Interurban rail lines eventually thickened these linkages, bringing Waukesha and Hales Corners into daily contact with the Central Business District of Milwaukee. Passenger trains along the Milwaukee Road, as well as the Chicago and North Western, moved people from across southeastern Wisconsin into contact with the Menomonee Valley for work or with downtown Milwaukee for the purchase of communion and wedding dresses. In the post-World War Two era, the interstate freeway system provided an alternative system for knitting the region together. Everyday behavior—some leisure-oriented, occasionally religious in intent, often economic in outcome—operated on a routine basis without reference to villages, cities, or towns—and their restrictive borders.

In 1955, however, the state legislature’s passed what became known as the Oak Creek Law, a piece of legislation that quickly politicized the natural competition between Milwaukee and its fast-growing hinterlands. This law hardened jurisdictional divisions between the core city and its surrounding communities.[2] It also politicized the racial divides between the city’s expanding African American population and a suburbanization process fed by white flight. Deindustrialization then finished the dismantling of century-old links between Milwaukee-based jobs and the region’s residential living patterns.

This fracturing of Milwaukee’s organic metropolitanization was largely completed by the 1990s. Yet examples of cross-jurisdictional cooperation survived—even flourished—in spite of political warfare between the core city and its suburbs. Since 1960 the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission has provided seven neighboring counties with technical expertise and planning assistance for highways, water and sewerage systems, management of open space, and environment challenges.[3] In 1979, cross-municipal cooperation initiated a process whereby a single public library could eventually serve the communities of Bayside, Fox Point, Glendale, and River Hills.[4] A little more than a decade later similar sentiments led to the North Shore Fire Department, whose Vision Statement recognizes that cooperation must never be “hampered by territorialism or parochialism.”[5] More recently, a regional framework shaped the decision to allow Lake Michigan water to flow west to Waukesha residents across the Subcontinental Divide and may over the next few years lead to the possible unification of the Metropolitan Milwaukee and Greater Waukesha County YMCAs.

Routine interactions of people across artificial borders make available the life-saving resources of Froedtert and St. Luke hospitals, lead enthusiasts to Summerfest and Miller Park, or take parents and their children south to Racine’s Apple Holler for Halloween festivities or north to Washington County’s Holy Hill. Our challenge in the twenty-first century remains as to whether everyday metropolitanization is an interactive process that unifies or a political tool that divides.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 111, 245, 250, 251.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 340.

- ^ “About Us,” Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission website, accessed April 3, 2017.

- ^ “About NSL,” North Shore Library website, accessed April 4, 2017, http://mcfls.org.

- ^ “Vision Statement/Organizational Values,” North Shore Fire Rescue website, accessed April 3, 2017.

For Further Reading

McCarthy, John M. Making Milwaukee Mightier. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009.

Orum, Anthony M. City-Building in America. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995.

Rodriguez, Joseph A. Bootstrap New Urbanism: Design, Race, and Development in Milwaukee. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.