The relationship among Kenosha, Milwaukee, and Racine Counties has always been problematic, reflecting the dueling influences of Wisconsin and Illinois over their development. As one measure, consider how the U.S. Census Bureau officially designates their relationships. Although Racine is part of the Milwaukee-Racine-Waukesha WI Combined Statistical Area, Kenosha is not. Instead, the Census Bureau affiliates Kenosha, the southeastern-most county in Wisconsin, with the Chicago-Naperville-Elgin Metropolitan Statistical Area, which also encompasses eight counties in Illinois, as well as four counties in northwestern Indiana.[1] Together, Kenosha and Illinois’s Lake County constitute a Metropolitan Statistical Area.[2] Most Kenosha residents who commute to another county for work travel to Lake County,[3] and transplants from Illinois frequently refreshed Kenosha’s population.[4]

Looking northward, Kenosha and Racine have engaged in a sometimes bitter rivalry that often prevented cooperation. Early on, they squabbled over federal funds to dredge their harbors and locate their postal services. During the 1960s, they clashed over where to construct the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Parkside. Eventually, the Wisconsin legislature chose Somers, adjacent to Petrifying Springs County Park in Kenosha, just south of Highway KR. Today’s student body is nevertheless proportionately representative of both counties, while dormitories have helped to break down the geographical division, as well as attracting students from outside the two counties. As late as 1990, Kenosha’s population was only 128,181, compared to 175,034 for Racine and 959,963 for Milwaukee. From that point onward, though, the state’s two southeastern-most counties have grown at a remarkably similar pace—to 195,408 for Racine and 166,426 for Kenosha by 2010.[5]

Kenosha County was established on January 30, 1850. Its present boundaries are Highway KR on the north; Lake Michigan on the east; the Illinois state line on the south; and Highway 83 on the west. The county contains six villages (Bristol, Paddock Lake, Pleasant Prairie, Silver Lake, Somers, Twin Lakes); and is subdivided into six towns (Brighton, Paris, Randall, Salem, Somers, and Wheatland).[6] The last two towns (Somers and Wheatland) constitute a tight-knit conurbation on the lakeshore, named Southport in 1837 and incorporated as the city of Kenosha in 1850. In 1957, Kenosha was divided east and west by Interstate 94, i.e. the Chicago-Milwaukee corridor.[7]

At the onset of the twentieth century, Kenosha’s population was the product of two simultaneous migrations. The first were descendants of Yankees, from New England and New York, under the aegis of the Western Immigration Company. The second consisted of immigrants from northern and western Europe and the British Isles. Kenosha’s phenomenal growth over the next three decades was fueled by newcomers from southern and eastern Europe, who transformed the county into a patchwork quilt of ethnicities. In 1850, it was still more than fifty percent Yankee, but immigrants from Germany, Ireland, and Great Britain were already making a substantial impact. By 1875, the compiler of the City Directory pronounced Kenosha “a fair mixture of all nationalities, Americans, English, Germans, and Irish prevailing.” He estimated that about one-third of the settlers over the past three decades were foreign-born and that “a much larger proportion of their children rather than of the native inhabitants has remained with us and they constitute today the laboring masses of our people from whose sinew and bone come the wealth and prosperity of the place.” At the turn of the century, Kenosha had a Yankee-British core, almost equaled in size by a combination of Germans, Scandinavians, Irish, and other northwestern European newcomers.

Over the next thirty years, the city’s population quadrupled.[8] About thirty percent of that increase was due to the immigration; nearly three-fourths of those were Italians, Poles, Russians, Lithuanians, Finns, Ukranians, Austrians, Hungarian Magyars, Czechs, Slovaks, Serbians, Slovenes, Croatians, Greeks, Armenians, and Jews from the “Pale of Settlement” in western Russia. In three decades, southern and eastern Europeans had almost achieved parity. It was not until the World War I era that African Americans from the South began to settle in any appreciable numbers. Starting with migrant workers in the 1930s, Mexicans from Texas and the mother country began to arrive in small numbers. A dramatic increase in the number of African Americans and Mexicans in the city’s population did not occur until World War II.[9]

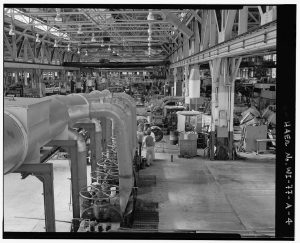

In 1890, the City of Kenosha was still a small place whose residents were predominantly engaged in non-manufacturing pursuits. In the thirty years between 1890 and 1920, it was transformed into a fairly major industrial area. The population of Kenosha city spurted from 6,532 to 40,472, moving it from seventeenth to third among Wisconsin’s cities. Manufacturing employment increased from barely 1,000 to more than 13,000 positions, while the total value of its industrial output jumped from $2.5 million to $103.7 million. By 1920, it ranked behind only Milwaukee and Racine in number of wage-earners and value added by manufacturing. Establishing a ratio that prevailed until the 1970s, its five largest employers—Nash Motors, Simmons Manufacturing Company, American Brass, Black Cat Textiles, and N.R Allen Sons Company tannery—accounted for 85 percent of the total jobs in the city. Moreover, the city’s products have been heavily skewed toward durable goods composed of iron, steel, and other fabricated metals. While both Milwaukee and Racine once manufactured a sizeable amount of automobiles and auto parts, twentieth-century Kenosha industry has been largely dominated by Nash/American Motors. At its highest point in the 1940s, it employed almost 16,000 workers at union scale plus substantial benefits. Even at the time of its plant closing in 1988, it still accounted for ten percent of the city’s workforce.[10]

While still adjusting to the shock, community leaders formed a Transition Team that engaged in a year-long planning process. It negotiated a $220 million closing settlement with Chrysler that included separation pay, the cost of razing the buildings, and a $9 million fund to pay for education for workers and their families. It also attracted smaller industries with local headquarters. The city oversaw development of HarborPark, an adjacent 350-unit condominium project of the same name, and a new Public Museum; installed an old-fashioned streetcar system; worked to attract businesses and residents from Lake County; and developed Lakeview Corporate Park in Pleasant Prairie, which contained factories and warehouses employing 7,000 people. Especially noteworthy are the Meijer Chain Distribution Center, the Walmart/Sam’s Club Complex, and the 1-million-square-foot Amazon.com Fulfillment and Sortation Center.[11]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Map, Chicago-Naperville, IL-IN-WI Combined Statistical Area, US Census Bureau website, last accessed February 12, 2019; Kenosha County, Wikipedia, last accessed February 12, 2019.

- ^ Rich Reinhold, “Changes to Illinois Metropolitan Statistical Area Delineations Following the 2010 Census,” Illinois Department of Employment Security, Economic Information and Analysis Division, last accessed January 31, 2019.

- ^ Kenosha County Out-Commuter Analysis, Kenosha Area Business Alliance, March 2016, last accessed February 12, 2019.

- ^ “Census: Many Move Here from Suburbs of Chicago,” Kenosha News, March 28, 2008. See the Understory to this entry for a further development of the ideas underlying this sentence and the research leading to this citation.

- ^ “State & County QuickFacts,” United States Census Bureau, retrieved January 21, 2014; “Kenosha County, Wisconsin,” Wikipedia, accessed August 2016.

- ^ “Population and Political Subdivisions,” 2017-2018 Wisconsin Blue Book, accessed August 6, 2018.

- ^ “State and County Facts,” U.S Census Bureau, retrieved 2014; “Kenosha County, Wisconsin,” Wikipedia, accessed August 2016.

- ^ For an accessible summary of Kenosha’s demographic patterns, see “A Comprehensive Plan for the City of Kenosha: 2035,” City of Kenosha, accessed August 8, 2018.

- ^ John D. Buenker, “Immigration and Ethnic Groups,” in Kenosha County in the Twentieth County, ed. John H. Neuenschwander (Kenosha, WI: Kenosha County Bicentennial Commission, 1977), 1-40.

- ^ Richard H. Keehn, “Industry and Business,” in Kenosha County in the Twentieth County, ed. John H. Neuenschwander (Kenosha, WI: Kenosha County Bicentennial Commission, 1977), 175-203.

- ^ “Timeline—Kenosha Wisconsin in Auto History,” Kenosha News, October 11, 2009; Stacy Vogel, “20 Years after Plant Closure: Kenosha Has Rebuilt Its Economy, Kenosha News, June 8, 2008.

For Further Reading

Burckel, Nicholas C., and John A. Neuenschwander, eds. Kenosha Retrospective: A Biographical Approach. Kenosha, WI: Kenosha County Bicentennial Commission, 1981.

Neuenschwander, John A., ed. Kenosha County in the Twentieth Century: A Topical History. Kenosha, WI: Kenosha County Bicentennial Commission, 1976.

See Also

Explore More [+]

Understory

A Peek into Editing the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee

Do you ever wonder how an entry in the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee (EMKE) moves from the author’s draft to its published form? Looking at a single sentence in the Kenosha County entry opens a window in the EMKE research and editing process.

The first paragraph of the original draft of the Kenosha entry explained why US Census Bureau’s statistics associate Kenosha with Chicago, Naperville, and Elgin in Illinois instead of with Milwaukee, Racine, and Kenosha. One sentence read like this: “Its reasoning is that ‘the county has traditionally attracted newcomers from suburban Chicago, and in March 2008 the demographers of the Wisconsin Department of Administration reported that Kenosha County’s improvements in roads, business’s need for personnel and quality of life factors have contributed to a decades-long influx of Illinois transplants.’”[1]

By the end of the initial round of editing, the text had been rewritten to read, “It does so because ‘the county has traditionally attracted newcomers from suburban Chicago.’ Moreover, the Wisconsin Department of Administration reported, in March 2008, that ‘improvements in roads, business’s need for personnel and quality of life factors have contributed to a decades-long influx of Illinois transplants.’”[2]

So, now I knew the origin of the Wikipedia phrase. Was there a published report underlying the demographer’s interview? Thanks to Google, I was able to identify a current email address for the quoted demographer and ask him directly whether he thought the quotation resulted from a reporter’s interview or in response to the publication of report. He responded promptly and told me that he thought there was no report.[13]

So, what did all of this research tell me? I had identified the origins of the sentence about migration from Chicago suburbs to Kenosha. The author of the sentence in Wikipedia had interpreted the demographer’s comments in the Kenosha News as a report, not an interview, making the entire sentence sound so authoritative it got picked up by a wide variety of other online sources about Kenosha County. Now my choice as an editor was to leave the original sentence roughly intact, changing it subtly to reflect what I understood about its origins, find a better source for the same information and rewrite accordingly, or change that line altogether. If you look back at the opening paragraph of the Kenosha County entry, can you tell what choice I made?

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Draft dated July 29, 2016, on file in the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee digital back end system.

- ^ Draft dated October 4, 2017, on file in the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee digital back end system.

- ^ Wikipedia: No Original Research, Wikipedia, last accessed February 8, 2019; see also Timothy Messer-Kruse, “The ‘Undue Weight’ of Truth on Wikipedia,” The Chronicle of Higher Education online, February 12, 2012.

- ^ Kenosha County, Wikipedia, last accessed February 7, 2019.

- ^ Kenosha County, Wisconsin, eReference Desk (with “businesses’ need”); Kenosha County, Wisconsin Facts for Kids, Kiddle website; Careers, Jobs and Education Resources for: Kenosha County, Wisconsin, Careers.org; Kenosha County, Wisconsin, WikiVisually website; 063 WGA Geo-Art, Geocaching website; Kenosha County Information, WikiTree; Kenosha County, Davis Hunter website; Kenosha County, Wisconsin, Familypedia; Kenosha County, Wisconsin, TheInfoList.com; all accessed February 7, 2019.

- ^ Email correspondence between Amanda I. Seligman and Dan Barroilhet, January 31, 2019 to February 7, 2019, in author’s possession.

- ^ Internet Archive Wayback Machine search results, last accessed February 8, 2019.

- ^ Document Center Library, State of Wisconsin—Department of Administration website, archived on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine, last accessed February 8, 2019.

- ^ DFDM Document Library, Wisconsin Department of Administration website, last accessed February 8, 2019.

- ^ Kenosha County, Wisconsin: Difference between Revisions, Wikipedia, last accessed February 8, 2019.

- ^ Wisconsin Newspaper Association Archive of Wisconsin Newspapers, last accessed February 8, 2019.

- ^ “Census: Many Move Here from Suburbs of Chicago,” Kenosha News, March 28, 2008, p. A9, accessed through Wisconsin Newspaper Association Archive of Wisconsin Newspapers.

- ^ Email correspondence with David A. Egan-Robertson, February 7, 2019.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.