Irish and Irish-American residents have been an important part of southeastern Wisconsin since the 1830s, creating a distinctive subculture that combined engagement in civic and business affairs with attention to cultural and political concerns in Ireland.

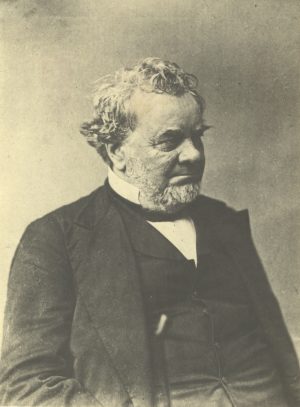

As early as 1839, Dublin-born lawyer, journalist and businessman Hans Crocker helped launch the Milwaukee Lyceum—the precursor to the Milwaukee Public Museum. He later served as the city’s mayor and then became a partner in the Milwaukee Manufacturing Company.[1] Clearly an exceptional figure, he exemplified the earliest Irish settlers in the USA in that they were more likely to come from the north and east of Ireland than later migrants, and they included a higher percentage of middle-class, educated settlers than would be the case after 1845, when a potato famine rocked Ireland. That disaster catalyzed changing emigration patterns, such that poorer people from the south and west left the island in larger numbers.[2] By 1850, when the share of Irish settlers peaked in the area, roughly 14 percent of Milwaukee’s 20,000 residents were ethnically Irish, and nearly 1,500 more were scattered throughout Milwaukee County. During the 1850s, two-thirds of Irish men in the city were manual laborers, while Irish women often worked as domestic servants. Almost three-fifths of the city’s Irish rented their residences, while those in surrounding communities sought to establish farmsteads with limited means.[3]

Pre- and post-famine settlers shared two characteristics: they rarely came directly to Wisconsin from Ireland, and they usually spoke English before arriving. It is possible that these two factors were related. Conzen’s study of the 1860 census, for instance, shows that 57 percent of the Irish-born residents of Milwaukee’s Fourth Ward came from seven contiguous counties in Munster and Connacht, a region that remained majority Irish-speaking or bilingual.[4] Because most then spent an average of seven years in Canada or the eastern United States before moving to Wisconsin, they had almost certainly learned the language prior to answering the advertisements and books written by emigration agents promoting the area. One such agent, the Kerry-born John Gregory, arrived in Milwaukee in 1849 and, with David Power, founded the American Emigration Co-operative Agency, which facilitated their movement and adjustment to their new home.[5]

For many, initial opportunities amounted to the hard work of leveling hills, filling swamps, and building Milwaukee’s streets. Much of that labor was applied to the neighborhood with the highest concentration of Irish settlement (some 37 percent), the Third Ward. South of the main business district and abutting the lake, the ward sat on reclaimed marshland that occasionally flooded.[6] Residents nonetheless had access to jobs on the city’s docks and at the local gas works; others worked as day laborers cleaning the cobblestone streets under the direction of local personality, city marshal Timothy O’Brien. The neighborhood also earned a nickname in the 1850s as the “Bloody” Third Ward, partly because drink-fueled violence spilled out from the saloons that ringed its outer edges. In 1858, according to John Gurda, 41 percent of those who spent time in the county jail were natives of Ireland.[7] Such evidence should be balanced by recognition that temperance crusades garnered interest among the Irish at home and in the USA. Indeed, the first St. Patrick’s Day parade in Milwaukee, in 1843, was sponsored by the Wisconsin Total Abstinence Society. It drew 3,000 marchers from throughout southeastern Wisconsin, and the society’s city branch claimed between 600 and 700 members.[8]

Uniformed service also shaped adaptation to the area. Militia corps, fire companies, and the nascent police and sheriff’s forces provided employment and camaraderie.[9] Famously, one of the most shocking incidents to affect the local Irish came when one of these militia corps (the Union Guards) organized a fund-raising trip to Chicago aboard the ship, Lady Elgin, in 1860. Heading home, the Lady Elgin collided with another vessel, and nearly 300 of the 400 passengers drowned, including several leaders of the Third Ward.[10]

Ongoing ties to Ireland were often fostered through organized religion, most especially Roman Catholicism. St. Peter’s Church, the first Catholic parish in Milwaukee, split during its early days into German-speaking and English-speaking (but ethnically Irish) congregations. The latter group became closely associated with the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist from the time its cornerstone was laid in 1847. As the city expanded westward, new congregations, such as St. Gall’s, Gesu, and St. Rose parishes, serviced those families associated with the spread of the Irish along the Menomonee River Valley toward Tory Hill (under what is now the Marquette Interchange) and out to and beyond the edge of the city. That movement sped up dramatically in 1892 when a fire devastated the Third Ward, destroying 440 buildings and leaving 2,000 people homeless. Priests and nuns in these parishes were often immigrants or first-generation Americans. Imitating mid-nineteenth-century Irish practice, they encouraged a close associational culture through organizations such as the Hibernian Benevolent Society—a forerunner of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Young Men’s Sodality, and the St. Ann’s Society (through which women and girls tended to clerical vestments and cleaned church sanctuaries).[11]

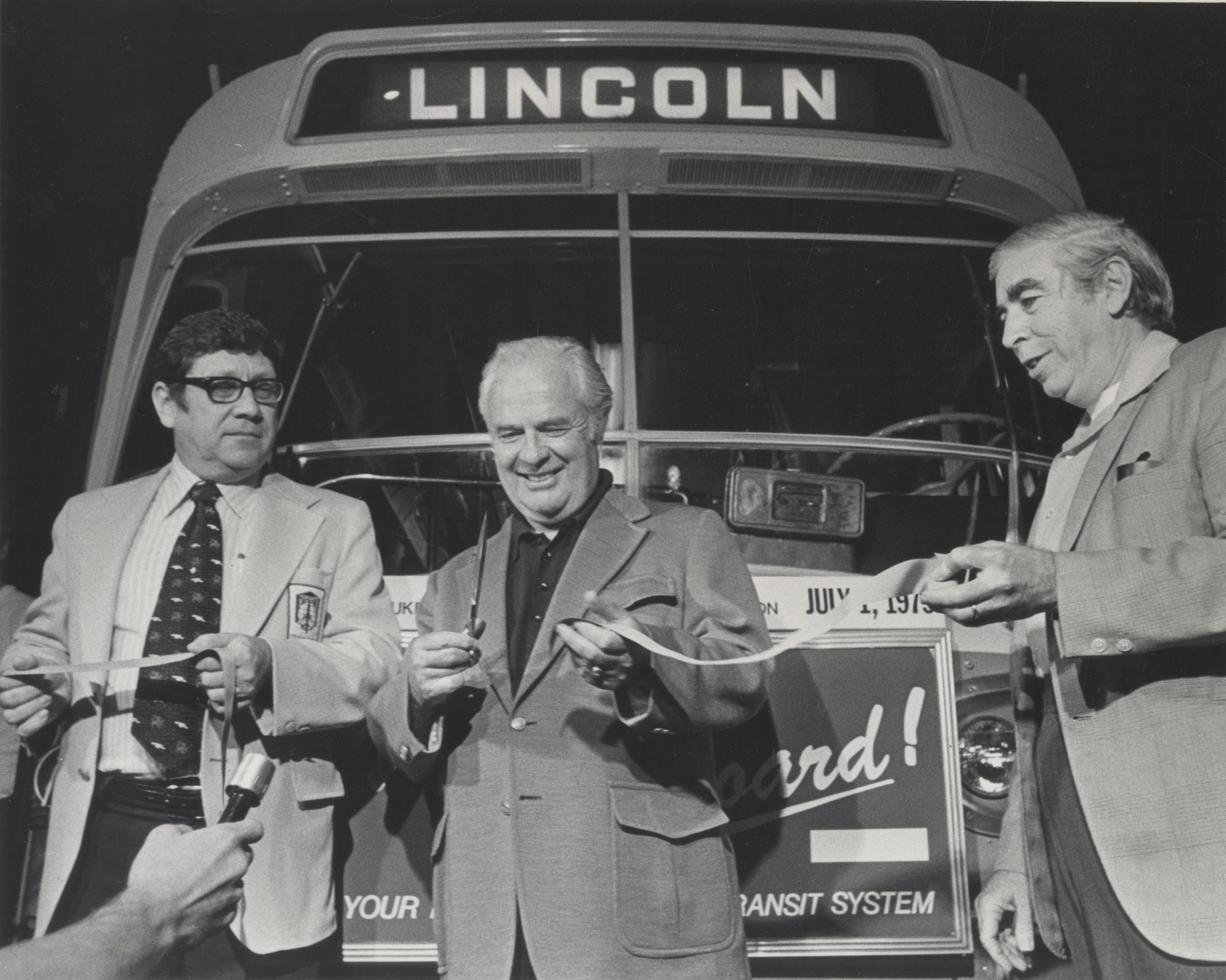

The ability to organize also manifested itself politically, usually to the benefit of local Democratic candidates or to Irish nationalism overseas. Irish politicians shaping Milwaukee throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries included figures such as Cornelius Corcoran (alderman for the Third Ward from 1892 until 1935), Daniel Webster Hoan (Socialist mayor of Milwaukee from 1916 until 1940), and William O’Donnell (county supervisor and then Milwaukee County Executive from 1963 until 1988).[12] Irish Milwaukeeans have also raised funds for and awareness of causes in Ireland, ranging from collecting funds for famine relief in the 1840s to supporting youth programs, such as the Ulster Project, during the civil strife of the late-twentieth century in Northern Ireland. The surge in immigration from Ireland to the U.S. ended by the early twentieth century, and in 1930, only 1.4% of the Milwaukee metropolitan population (some 11,000 people) reported to the census that their fathers were born in Ireland. Nevertheless, the current census surveys report that 8 percent of metro Milwaukeeans (over 160,000 people) report that they are of Irish ancestry.[13] Indeed, while they have assimilated into the wider culture of the state during the twentieth century, the Irish of southeastern Wisconsin continue to express their heritage, most notably through Milwaukee’s Irish Fest (founded in 1981), the largest festival of Irish culture in the world.[14]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Robert W. Wells, This Is Milwaukee (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1970), 122; Martin Hintz, Irish Milwaukee (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 21; Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1976), 205.

- ^ For context, see Kerby A. Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 67-75 passim; Martin Hintz, Irish Milwaukee (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 7; David G. Holmes, Irish in Wisconsin (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2004), 16; Harry H. Anderson and Frederick I. Olson, Milwaukee: At the Gathering of the Waters (Tulsa: Continental Heritage Press, 1981), 23; and John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 66.

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 24-25; Garrett Fitzgerald, “Estimates for Baronies of Minimum Level of Irish-Speaking Amongst Successive Decenniel Cohorts: 1771-1781 to 1861-1871,” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 84c (1984): 117-55.

- ^ Holmes, Irish in Wisconsin, 17; Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 41; Hintz, Irish Milwaukee, 7.

- ^Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 142; Hintz, Irish Milwaukee, 9; Wells, This Is Milwaukee, 83-84; Cile Miller, “St. Patrick’s Adopted Soil—the Old Third Ward Before the Fire: Irish of Yesterday Added Spice to the Milwaukee of Later Time,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 19, 1933.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 66.

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 160.

- ^ Hintz, Irish Milwaukee, 81; Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 171.

- ^ Wells, This Is Milwaukee, 84-85; Hintz, Irish Milwaukee, 13.

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 160-62; Hintz, Irish Milwaukee, 33-38 passim; Austin, Milwaukee Story, 153; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 66, 72; John Gurda, “Freeway to Oblivion: Marquette Interchange Erased the Tory Hill Neighborhood,” in Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 2007), 57-59.

- ^ Hintz, Irish Milwaukee, pp. 62-63; Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 205; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 70; Wells, This Is Milwaukee, 83-84.

- ^ Father’s Birthplace, 1930 5% Sample of the U.S. Census of Population, tabulated from IPUMS-USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org; U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder, Total Ancestry Reported, 2009-2013, American Community Survey Five Year Estimates (B04003); factfinder.census.gov.

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 171; Hintz, Irish Milwaukee, 93-128 passim; and Jim Hazard, “The Great Green Awakening,” Milwaukee Magazine 21:8 (Aug. 1996): 52-56.

For Further Reading

Conzen, Kathleen Neils. Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976.

Gurda, John. The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999.

Gurda, John, editor. Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 2007.

Hintz, Martin. Irish Milwaukee. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

Holmes, David G. Irish in Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2004.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.