The Milwaukee County Zoo is considered among the nation’s finest zoological attractions.[1] Located just off of Interstate 94 and Interstate 41, the Zoo offers over 3,100 animals in naturalistic exhibits along with many amusements and special events.[2] Visitors particularly enjoy the Zoo’s annual Halloween event, Boo at the Zoo, and the Sunset Zoofari, an evening event that invites patrons to visit the animals while enjoying live music.[3]

The Early Years at Washington Park

As German immigrants flocked to Milwaukee during the second half of the nineteenth century, they sought to recreate the homeland they had left behind. In 1892, two prominent German-American Milwaukeeans, Colonel Gustave Pabst (son of Frederick Pabst, owner of Pabst Brewery) and General Louis Auer, donated eight deer to Milwaukee’s newly opened West Park in the effort to create a deer park, common in Germany. Designed by Frederick Law Olmsted’s landscape and architecture firm, West Park opened in 1892.[4] As the small deer park grew, it was renamed Washington Park Zoo in 1900. Additional animals were donated early in the century, including a cinnamon bear, two black bears, a bald eagle, and monkeys. The new animals necessitated the further development of zoo infrastructure, especially after Jack the cinnamon bear ate through the walls of the barn where he was living. These new additions included the Eagle Aviary and the Animal House, which allowed year-round access to the zoo.[5]

In 1910, the Washington Park Zoological Society formed in order to build membership and ensure financial stability.[6] A year later, the Society had 163 members and $500 in the treasury. Today, the society exists as the Zoological Society of Milwaukee and in 2014 had over 50,000 household memberships.[7] Its mission is to educate the public on the importance of wildlife and conservation.

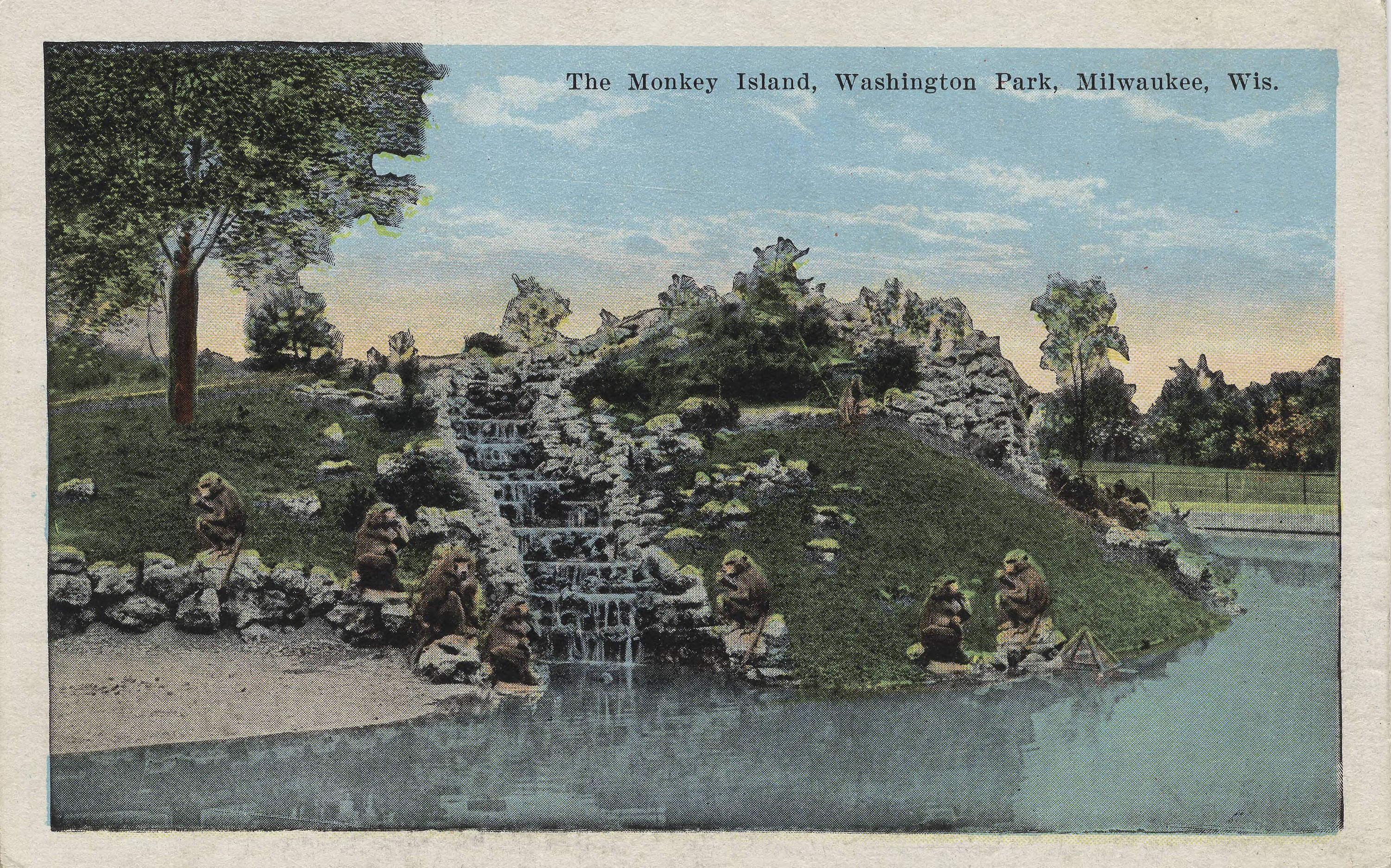

Under the auspices of the Zoological Society, the zoo quickly became a popular tourist destination in Milwaukee. Paved roads and the installation of lights allowed it to stay open at night. Washington Park itself featured a lagoon for boating and many picnic areas; it also held concerts in a large concert shell constructed for Washington Square Park. These concerts often raised funds for the Zoo. Edward Bean, the Zoo’s Director, oversaw the acquisition of many new animals that drew even more crowds; Bean later became first director of the Brookfield Zoo, west of Chicago. In 1917, a bond issue raised $40,000 was to build an exhibit for carnivorous animals.[8] Four years later, Monkey Island was built; it was the first of its kind in the country.

During the years of the Great Depression, the Zoological Society faced financial setbacks, yet the Zoo remained free for the public. In fact, the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration provided funds to build bear dens in 1932-1933. In another effort to keep the Zoo afloat, food for the animals was grown on local farms.[9] On January 1, 1937, voters approved a referendum that consolidated the Milwaukee City and County Park systems, thereby transferring authority over the Zoo from the city to the county government. Thereafter, the County Park Commission worked in tandem with the Zoological Society to support the care and development of the Zoo. As the Zoo continued to expand despite the economic constraints of the period, the Zoological Society lobbied the County Park Commission to move the Zoo to a new location with room to expand. Eventually the Commission sanctioned the move and, beginning in 1947, purchased over two hundred acres of land south of Bluemound Road alongside Highway 100. The Milwaukee County Zoo officially opened fourteen years later on Mother’s Day, 1961.[10]

From a Humble Deer Park to the Award-Winning Milwaukee County Zoo

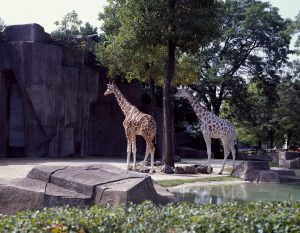

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Zoo developed a number of new exhibits, which focused on imitating animals’ natural environments. Money for the new initiatives came primarily through donations and fundraising campaigns by prominent Milwaukee businesses, such as the Pabst Brewing Company and the Pfister Hotel.

In October of 1959, the Zoo opened a miniature railroad, which allowed visitors a new way of experiencing the Zoo. It became an instant hit. A new polar bear exhibit featuring an underwater viewing area and a feline house attracted more visitors to the Zoo. The popular Monkey Island was rebuilt in the new location. When the zoo officially opened, it drew crowds from all across the greater Milwaukee area. The process of transitioning from one location to another did not occur overnight; however, by 1963 all animals had been moved.[11]

Beginning in the late 1960s, especially following the passage of the 1969 Endangered Species Conservation Act, the Milwaukee County Zoo expanded its focus on conservation and educational programs. The Zoo established the Zoo Pride Volunteer Auxiliary in 1975, which continues to this day. Its mission is to help educate the public on wildlife ecology and environmental conservation. Indeed, education has become a primary focus of the Zoo. This is seen through informational graphics placed around the Zoo, educational programs for children, and the Karen Peck Katz Conservation Education Center, built in 2004.[12] Additionally, in 1989 the Zoo established the Animal Ambassador Program, which serves as an educational outreach program to teach children from low-income schools about animals, ecology, and zoological careers. Notable additions to the Zoo from the 1950s to the present day include the Aquarium and Reptile Building, known for its Lake Wisconsin tank filled with native fish (1968) and the Children’s Zoo, which includes a working dairy farm (1971).[13] After the first siamang (a member of the Gibbon family) was born in capacity in 1962, the Zoo received an Edward H. Bean Award for reproductive management from the prestigious American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums.[14] A little over a decade later, the Milwaukee County Zoo launched a New, New Zoo campaign, which raised over $25 million to bring the Zoo into the next century by modernizing exhibits and placing a greater emphasis on conservation and education.[15]

Famous Animals

Over the course of its history, the Milwaukee County Zoo has been home to many remarkable animals. In 1907, the Zoo acquired an elephant named Countess Heine. Her arrival was celebrated by a parade through Milwaukee, during which the elephant was brought to the Pabst Brewery, where she was presented with a sheaf of hay wrapped in a blue ribbon (like the famous bottles of Pabst Beer). Countess Heine was a favorite among guests who especially enjoyed elephant rides.[16]

In 1928, on a safari in Africa, staff of the Milwaukee Public Museum found an orphaned lion cub on a safari in Africa. Affectionately named Simba (which means “lion”), he was brought back to Milwaukee and lived in the Taxidermy department of the Museum, where he was allowed to roam freely. Simba eventually was moved to the Milwaukee County Zoo, where he was renamed Sim.[17]

Perhaps the best-known resident of the Milwaukee County Zoo was Samson the Gorilla. Samson and his brother Sambo were brought to the Zoo when they were about a year old in 1950. Thirty-two thousand visitors attended the opening of their exhibit. Samson quickly grew to an astonishing weight of 652 pounds. He was known for running at the glass of his exhibit and pounding on it with his first. While he never broke the glass, he did crack it four times, much to the terror of Zoo visitors. He died at the age of 32 in 1981. A “recreation” of Samson—which won several taxidermy awards—still greets visitors to the Milwaukee Public Museum.[18]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “Milwaukee County Zoo,” U.S. News and World Report, accessed November 30, 2017.

- ^ “Home: Welcome to the Milwaukee County Zoo,” Milwaukee Zoo website, accessed November 25, 2017

- ^ “Milwaukee County Zoo,” U.S. News and World Report, accessed November 30, 2017.

- ^ Bobby Tanzilo, “Washington Park Zoo Has Left Nary a Trace,” OnMilwaukee.com, May 29, 2011, accessed November 25, 2017.

- ^ Darlene Winter, Elizabeth Frank, and Mary Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2014), 12-19.

- ^ “About Us: The Zoological Society of Milwaukee,” Zoological Society of Milwaukee website, accessed November 25, 2017.

- ^ Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 19.

- ^ Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 30.

- ^ Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 33.

- ^ Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 33-35.

- ^ Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 62.

- ^ “About Us: The Zoological Society of Milwaukee,” Zoological Society of Milwaukee website, accessed November 25, 2017.

- ^ Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 72-75.

- ^ “Edward H. Bean Award,” Association of Zoos and Aquariums website, accessed November 25, 2017.

- ^ Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 67.

- ^ Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 18-19.

- ^ “Milwaukee’s Menagerie: Sim the Library Lion,” Milwaukee Public Library website, last modified April 8, 2015, accessed November 25, 2017.

- ^ “Milwaukee’s Menagerie: Samson the Gorilla,” Milwaukee Public Library website, last modified April 29, 2015, accessed November 25, 2017; “Samson,” Milwaukee Public Museum website, accessed October 27, 2018.

For Further Reading

Albano, Laurie Muench. Milwaukee County Parks. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2007.

Koeber, Linda. Zoo Book: The Evolution of Wildlife Conservation Centers. New York, NY: Forge, 1994.

Winter, Darlene, Elizabeth Frank, and Mary Kazmierczak. Milwaukee County Zoo. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.