Although now merely a shadow of itself, the production of leather and leather goods was once a key part of Milwaukee’s industrial history. The leather industry and city grew together as firms tanned, curried, and finished animal hides as well as manufactured a variety of finished products. Milwaukee matured into a leading national and international supplier of leather by the late nineteenth century.

Milwaukee’s leather industry developed rapidly with the frontier community. By 1840, small retail and repair shops offered saddles, harnesses, trunks, and other leather goods produced in New England.[1] Daniel Phelps, a Yankee settler, established the city’s first tannery on Clybourn Street between Thirteenth and Fourteenth Streets in 1842, and German immigrant Christoph Doerfler opened a tannery on what is now South Tenth Street later the same year.[2] These firms initiated the dominant roles Yankee and especially German settlers played in shaping the industry’s development in Milwaukee.

Milwaukee’s early tanneries were primarily “merchant-manufacturer” shops that formed through family connections or brief partnerships, and typically employed three or four workers.[3] These artisans either processed leather for other area craftsmen to use or made custom items on site.[4]

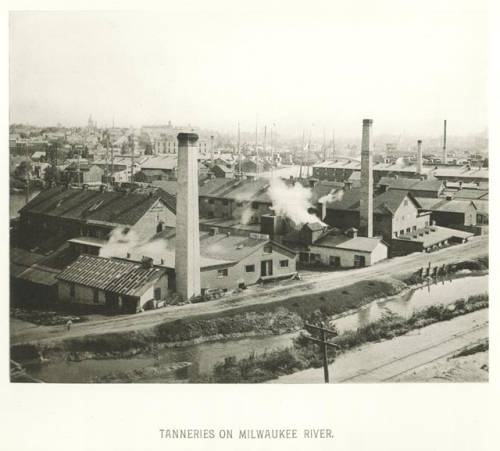

By the 1850s, a few larger leather manufacturers emerged as Milwaukee proved an ideal location for industrial tanning. Local farms and meatpackers provided hides, whereas abundant hemlock tanbark from northern Wisconsin and Michigan provided the tannin necessary to turn hides into workable leather.[5] Lake Michigan and the city’s rivers offered access to water necessary for the processing of hides while also providing transportation routes for shipping finished products to other markets, primarily back East.[6] Larger firms concentrated their operations over time into complexes along the Menomonee River, Kinnickinnic River, and especially the Milwaukee River.[7]

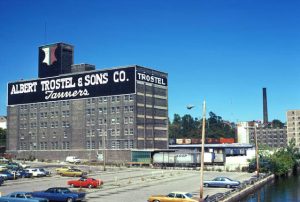

Milwaukee’s nascent industrial tanners often came to the city from New York and Germany, already experienced in industrial tanning processes. William Allen and Edward P. Allis (better known for his later venture that became Allis-Chalmers) moved to Milwaukee from Cazenovia, New York, a major center of the Northeastern U.S. leather industry where their families operated successful tanning businesses. Allen and Allis formed the Wisconsin Leather Company in 1851, headquartered on East Water Street in Milwaukee and initially supplied with processed hides by its tannery in Two Rivers.[8] Experienced German tanners Guido Pfister and Frederick Vogel established separate leather shops in Milwaukee in 1847 but merged their operations into the city’s largest industrial tanning firm in the Menomonee River Valley shortly thereafter.[9] Both the Wisconsin Leather Company and Pfister & Vogel quickly developed their operations with substantial capital investments from and partnerships with established family leather interests in Cazenovia and Buffalo respectively.[10] Other skilled German leather artisans who established small shops in Milwaukee in the 1840s and 1850s gradually expanded their operations into major tanneries by the 1870s.[11] Among these were Albert Trostel and August Gallun, who formed a partnership producing “Blue Star” harnesses in 1858. They later split into separate firms along the Milwaukee River, both of which remained in operation into the late twentieth century.[12]

Several factors generated continued growth of industrial tanning in Milwaukee. First, new railroad connections opened in the 1850s between Milwaukee and Chicago, and subsequently points east and west, allowing Milwaukee’s industrial tanners to import raw materials and export finished products in greater quantities and over longer distances.[13] Second, depleting sources of tanbark in the East shifted industry growth westward to places like Milwaukee where tanbark supplies were more plentiful.[14] Third, and perhaps most important, Milwaukee firms secured large government contracts to produce leather boots, cartridge belts, and harnesses for the Union Army during the Civil War. This not only pumped significant amounts of capital into Milwaukee’s leather industry but also increased national demand for high-quality Milwaukee leather.[15] While Milwaukee was home to at least nine tanneries that employed over 100 workers and processed around 70,000 hides a year in 1860, these numbers had more than doubled a decade later.[16]

Between 1870 and 1900, Milwaukee’s leather industry grew into a national and international production center. New mechanized systems and chemical innovations greatly reduced the time it took to tan hides and facilitated the processing of leather on a progressively larger scale.[17] As the industry consolidated, production increased, growing from 232,219 hides prepared in 1875 to 568,393 in 1885, 912,847 in 1895, and over 1.7 million in 1905.[18] Moreover, cheaper labor and port costs gave Milwaukee firms an advantage over competitors.[19] By 1890, Milwaukee became the largest leather producer in the world.[20]

Plain, tanned cowhide was the most common Milwaukee leather product, but a few smaller firms specialized in deerskin, sheepskin, or kidskin leather.[21] Although significant leather goods manufacturers, like the Bradley & Metcalf Shoe Co., flourished in Milwaukee through this period, most of the leather produced in Milwaukee went as a basic staple to major manufacturing centers in the East, Midwest, or Europe.[22]

Milwaukee’s tanneries were significant industrial employers, especially for German, Polish, and later Latino and black workers. These wages built ethnic communities by funding the development of homes, parishes, and businesses—especially in neighborhoods near major tanning centers, such as Walker’s Point and Brady Street.[23]

The industry boomed through the First World War, having been called on again to make boots, belts, and other leather products for the military.[24] However, wartime demand drove leather prices up to unprecedented levels, prompting the substitution of leather with newer, cheaper synthetic materials as well as greater competition from foreign producers.[25] Moreover, industrial machinery eventually made greater use of electric motors that did not require leather pulley belts, and the automobile increasingly supplanted the need for leather products commonly used in horse-drawn transportation.[26] Major firms like Pfister & Vogel, Trostel, and Gallun again made leather for the military during the Second World War and remained in operation into the late twentieth century. However, the industry as a whole never fully recovered and gradually faded away.[27] Only a few custom leather goods manufacturers remain.[28]

The leather industry had a tremendous impact on the city’s environment, polluting Milwaukee’s rivers as well as Lake Michigan with industrial chemicals.[29] Brownfields created by former tannery sites have, beginning in the 1980s, been cleaned and repurposed or redeveloped into condominium and retail complexes.[30]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Margaret Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier: Pioneer Industry in Antebellum Wisconsin 1830-1860 (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1972), 188-189.

- ^ While Walsh refers to the first German tanner in 1842 as Christopher Doerfler and Conzen as Christian Doerfler, John G. Gregory identifies this person as Christoph Doerfler. Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 189; Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), 105; John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vol. 1 (Chicago and Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke Publishing, 1931), 536; Charles Ernest Schefft, “The Tanning Industry in Wisconsin: A History of Its Frontier Origins and Its Development” (Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin, 1938), 23.

- ^ Walsh’s term, “merchant-manufacturer,” has been adopted here as an effective way to describe Milwaukee’s early artisan-based tanneries. Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 189-190.

- ^ Schefft, “The Tanning Industry in Wisconsin, ”20-21; Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 189.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 186; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 119; Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 188, 190-191; Schefft, “The Tanning Industry in Wisconsin,” 12.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 119; Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 188; Schefft, “The Tanning Industry in Wisconsin,” 12.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1:536-537; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 125; John Gurda, “The Menomonee Valley: A Historical Overview,” Renewthevalley.org, accessed November 20, 2014.

- ^ Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 189-190; James S. Buck, Milwaukee under the Charter, from 1847 to 1853, Inclusive, vol. 3 (Milwaukee: Syme, Swain & Co., 1884), 420.

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 105-106; Buck, Milwaukee under the Charter, 3:150.

- ^ Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 190.

- ^ Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier,, 189-190; Still, Milwaukee, 188.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 119-120; Still, Milwaukee, 188; Schefft, “The Tanning Industry in Wisconsin,” 26.

- ^ Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 190-191; Schefft, “The Tanning Industry in Wisconsin, ” 13-14, 49.

- ^ Schefft, “The Tanning Industry in Wisconsin, ”, 7; Industrial History of Milwaukee, the Commercial, Manufacturing, and Railway Metropolis of the Northwest (Milwaukee: E. E. Barton, 1886), 58-60.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 101.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 192-193; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 101; Milwaukee Chamber of Commerce, Forty-Eighth Annual Report of the Trade and Commerce of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Evening Wisconsin, 1906), 132.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 335; Gregory, 1:538; Schefft, “The Tanning Industry in Wisconsin,” 56-59.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 120; Still, 334; Milwaukee Grain and Stock Exchange, Thirty-Ninth Annual Report of the Trade and Commerce of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Evening Wisconsin, 1897), 159; Milwaukee Grain & Stock Exchange, Fifty-Fourth Annual Report of the Chamber of Commerce of the City of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Radtke Bros. & Kortsch, 1912), 149.

- ^ Industrial History of Milwaukee, 59-60.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1:537-538.

- ^ Milwaukee Chamber of Commerce, Forty-Ninth Annual Report of the Trade and Commerce of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Radtke Bros. & Kortsch, 1907), 51; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 120.

- ^ Industrial History of Milwaukee, 60.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 120, 125; Anthony M. Orum, City-Building in America (Boulder: Westview Press, 1995), 53-54; Judith T. Kenny, “Polish Routes to Americanization: House Form and Landscape on Milwaukee’s Polish South Side,” in Wisconsin Land and Life, ed. Robert C. Ostergren and Thomas R. Vale (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 263-81; Frank D. Alioto, Milwaukee’s Brady Street Neighborhood (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), 30-31; Zaragosa Vargas, Proletarians of the North: A History of Mexican Industrial Workers in Detroit and the Midwest, 1917-1933 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993), 89-90; Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-45, 2nd ed. (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 47.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 240.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1:537-538; Still, Milwaukee, 495; Schefft, 88-89.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 495; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 241; Schefft, “The Tanning Industry in Wisconsin,” 88.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 308; Still, 494-495; Ronald Anzia, “Trostel Keeps Country in Shoes,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 14, 1965, sec. 2, p. 5; “Trostel Confirms Closing of Tannery,” Milwaukee Journal, June 3, 1969, sec. 1, p. 1; Jeff Cole, “Tannery Shuts down Line, Lays off 35,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 20, 1993, sec. D, p. 1; Joel Dresang, “U.S. Leather to End All Business in Milwaukee; 600 Jobs Lost,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 2, 2000, 8.

- ^ “About Us,” Mitchell Leather Factory & Retail Store, accessed November 19, 2014.

- ^ Margaret Beattie Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes: An Environmental History, 1783-1933 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 127-128, 141; Robert C. Nesbit, History of Wisconsin: Urbanization & Industrialization 1873-1893, vol. 3 (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1985), 258; Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Remediation and Redevelopment Program, Trostel Tannery (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, February 2010); EPA Brownfields and Land Revitalization Program, Pfister & Vogel Tannery: Transforming Milwaukee’s Largest Brownfield into a Sustainable Benefit for the Community (Chicago, IL: Region 5, United States Environmental Protection Agency, July 2010).

- ^ Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Remediation and Redevelopment Program, Trostel Tannery; Tom Daykin, “Buyer Sees New Life for Tannery,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 1, 2007, sec. D, p. 3; EPA Brownfields and Land Revitalization Program, Pfister & Vogel Tannery; The Tannery website, accessed November 20, 2014.

My Father Thermon L. Jones Retired From This Company After Working 41 Years. He Loved This Work Place.