Perspectives on disabilities and how to incorporate individuals with disabilities into mainstream society have evolved over the past couple of centuries. People with disabilities were viewed as less than human and treated as such. The views of individuals with disabilities in the 1800s reflected the assessment of value and worth in society. For example, people with disabilities were referred to as experiencing “idiocy” as a result of incontrovertible impaired intellect. Feeblemindedness was also used to describe those with milder forms of intellectual deficit.[1] Other labels referring to intellectual capacity or the lack thereof at this time included, “idiot,” “moron,” “backward,” “imbecile,” and “dullard.”

Often, perceptions about people’s cognitive ability included assessments of their social, physical, and moral capacities. Views regarding the origins of a disability influence ideas about how to deal with these disabilities. A medical model of disability sees disabilities as originating within the person. Disorders or problems in behavior, communication, learning, social interactions, and problem solving are centered in the individual in the medical model.[2] Failures due to individual deficits lend themselves to separation, for the purposes of either removing the defect from society or curing the defect in a person.

As early as the eighteenth century, hospitals geared towards the treatment of patients considered to mentally disturbed, ill, or disabled were opened as an alternative to jails and other facilities with the primary purpose of treating or curing these individuals. Individuals with disabilities experienced a significant amount of abuse and neglect and were viewed to be difficulty to rehabilitate or cure.[3] In recognition of the inhumane treatment of people with disabilities and an increasing desire to intervene, the first special education school in the United States was created in 1817 by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet in Hartford, Connecticut.[4] Called the American Asylum for the Education and Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, it exists today as the American School for the Deaf.[5] Massachusetts created the Asylum for the Blind in 1832 and the Asylum for Idiotic and Feebleminded Youth in 1848. New York followed with the state’s first state school for children with mental handicaps in 1854.

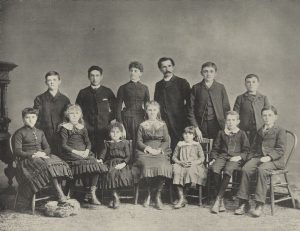

The move to create institutions for the education, rehabilitation, and treatment of children with disabilities was evident in Wisconsin, with the development of institutions for children with different disabilities. The Wisconsin Phonological Institute was formed in Milwaukee as a day school for the Deaf in 1879.[6] Through the advocacy of individuals such as Alexander Graham Bell, the Wisconsin state legislature supported the development of additional publicly-supported day schools for the Deaf in 1885. In 1876, the St. John’s Institute for Deaf-Mutes was created; it was patterned on the Boston-based Horace Mann School for the Deaf and Dumb.[7] Their approach was to place deaf mutes with their hearing and verbal age peers as much as possible.[8] Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) created the first day classes for the blind in 1907.[9] This initiative was followed by a school with classes for students with disabilities in 1913, supported by MPS superintendent Milton Potter. The school, which enrolled students with various disabilities, was renamed after Dr. Frederick J. Gaenslen, Milwaukee’s first orthopedic surgeon. The Frederick J. Gaenslen School continues today, with approximately half of their students having special needs.[10] Junior trade schools for both girls and boys appeared in Wisconsin with the extension of compulsory attendance from 14 years to 16 years in 1921. These schools had a vocational emphasis specifically geared towards children who did not show progress in academic learning.[11] In 1939, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction incorporated supervision of education at both residential and day schools under one Bureau for Handicapped Children.[12] This bureau oversaw the education of students including “the visually defective, the crippled, the deaf and hard of hearing, the speech defective, and the mentally handicapped.”[13] In 1943 Wisconsin continued its progressive support of children with disabilities by extending transportation support for students who were not in residential schools from not only the Deaf and physically disabled, but also to those with intellectual deficits.

These separate programs and institutions served the purpose of offering compulsory schooling. They also served the role of providing specialized instruction to reduce or eliminate the learning, social, communication, psychological, and behavioral deficits these students experienced. They also serve to keep students who might trouble a general education school or classroom, while simultaneously serving a protective function. Despite these perceived benefits, questions were raised on an ongoing basis regarding the quality of services and education provided. In the first half of the twentieth century, on the national level there was increasing recognition that the quality of education and rehabilitation offered in these separate schools were less than desirable.[14] Concerns included large class sizes, overcrowding, and inadequate staffing, inexperienced teachers with minimal training, problematic facilities, and lack of rigor and quality in the educational curriculum offered in these schools. As attitudes toward individuals with disabilities continued to evolve in post-World War II America, increased focus and attention was paid to the quality of education offered in separate settings. Despite the increased influx of resources reallocated to these separate facilities in the mid-twentieth century, and the support of separate classes and facilities, questions were raised about whether or not segregated education was actually providing quality education for children with disabilities.[15]

While communities, cities, and states were changing their support and treatment of individuals with disabilities through the development of different institutions, state and federal legislation was evolving as well.[16] Families of children with disabilities benefited from the claims successfully argued in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision stating that racially-driven segregation constitutionally protected access to equal educational opportunity. In 1965, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act was passed, allowing schools to receive federal funds for providing free public education to students. This funding support was expanded to include support for the education of children with disabilities in 1966. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act was passed in 1973. This federal mandate stated that people with disabilities have a right to equal access to public or private programs or activities receiving federal funding. People with disabilities could no longer be denied access or excluded on the basis of their disability. This was followed by the Education for All Handicapped Children Act signed into law in 1975 by President Ford. Fully implemented in 1977, this federal mandate required school districts across the nation to provide a free and appropriate public education to all students with disabilities. The Supreme Court decision in Board of Education of Hendrick Hudson Central School District v. Rowley, was a significant test of this legislation. In this decision, the U.S. Supreme Court reiterated that public schools are required to provide the supports needed to access public school programs and education for students who have demonstrated a need for special education services. The Court sought to insure that these students would be able to receive instruction in public school settings. In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) required compliance with federal law regardless of federal funding status for school districts. In 2004, the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act increased accountability in district assessments at specific grade levels for all public schools and included a requirement regarding the participation of the majority of students with disabilities in standardized assessments.

Since 1975, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act required the provision of special education services in the least restrictive environment, resulting in a continuum of placements where services are provided including: (a) being fully included in a general education setting; (b) receiving separate services in a resource room setting along with placement in a general education setting; (c) being placed in a self-contained special education classroom with some non-academic classes and activities with general education peers; (d) being placed in a self-contained special education classroom full-time; (e) being placed in a separate special education school; (f) being placed in a residential facility; and (g) being placed in a homebound placement or in a hospital.[17]

Despite the legal and social move toward integrated and inclusive education over the past several decades, special schools continue to exist in Wisconsin. Schools such as the Wisconsin School of the Deaf and Gaenslen School in Milwaukee Public Schools have long histories. Other schools are newer and include both private and public schools.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Robert Osgood, The History of Inclusion in the United States (Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 2005), 27.

- ^ Margret A. Winzer, The History of Special Education: From Isolation to Integration (Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 1993), 80.

- ^ Winzer, The History of Special Education, 66.

- ^ Osgood, The History of Inclusion in the United States, 20.

- ^ Osgood, The History of Inclusion in the United States, 20.

- ^ Belle Blend, “Milwaukee Leads in Deaf Education,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 3, 1907, Children in Urban America Project, last accessed June 18, 2018.

- ^ “Educational Intelligence,” Journal of Education 47, no. 23 (1898): 393.

- ^ M. M. Gerend, “The St. John’s Institute for Deaf-Mutes: St. Francis, WI 1876-1893,” in Histories of American Schools for the Deaf, 1817-1893 3, ed. Edward Allen Fay, vol. 3 (Washington, D.C.: The Volta Bureau, 1893), 183.

- ^ Carrie B. Levy, “Milwaukee’s Program of Special Education,” Journal of Exceptional Children 8, no. 5 (1942): 132-143.

- ^ Bobby Tanzilo, “Potter’s Legacy Lives on at Gaenslen School,” OnMilwaukee.com, February 12, 2012, last accessed August 16, 2018

- ^ Levy, “Milwaukee’s Program of Special Education,” 132-143.

- ^ Elise H. Martens, “Administration and Supervision of Special Education: A National Overview,” Journal of Exceptional Children 11, no. 3 (1944): 66-73.

- ^ Martens, “Administration and Supervision of Special Education”: 68.

- ^ Martens, “Administration and Supervision of Special Education”: 66-73.

- ^ Winzer, The History of Special Education, 315.

- ^ Osgood, The History of Inclusion in the United States, 36.

- ^ James Kaufmann, Jennifer Jakubecy, and Devery Mock, “Current Trends in Special Education,” in Encyclopedia of Education, ed. James W. Guthrie (New York, NY: Macmillan Reference, 2002), 2281-2290.

For Further Reading

Osgood, Robert. The History of Inclusion in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 2005.

Winzer, Margret A. The History of Special Education: From Isolation to Integration Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 1993.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.