James Groppi (1930-1985) was the most famous cleric in the history of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Milwaukee. He was born November 16, 1930, raised in a home attached to his family’s grocery store in Bay View, and attended nearby Immaculate Conception Church as well as Boys Tech and Bay View high schools. Feeling a call to the priesthood, he entered St. Francis de Sales Seminary of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee and was ordained to the priesthood in mid-1959.[1]

A critical moment came in his seminary education took place in 1956, when he was hired to become a counselor at a day camp for African American children. Working with these youngsters in the heart of the city’s black district sensitized him as never before to the depth of local racism—even from other Catholics. After ordination, he was first assigned to St. Veronica’s Church, a South Side working class parish. Here he performed the duties of the priesthood but grew upset with the negative attitudes his parishioners had toward African Americans and their indifference to his sometimes impassioned sermons denouncing racial hatred. His desire to work in an African American parish was granted in 1963 when he was transferred to St. Boniface Parish on 11th and Clarke. Two years later Groppi undertook a historic journey to Selma, Alabama. There he witnessed the brutality of the local police. He taught in a local “Freedom School” in Montgomery and came home with a desire to “do something” about Milwaukee’s racial issues.[2]

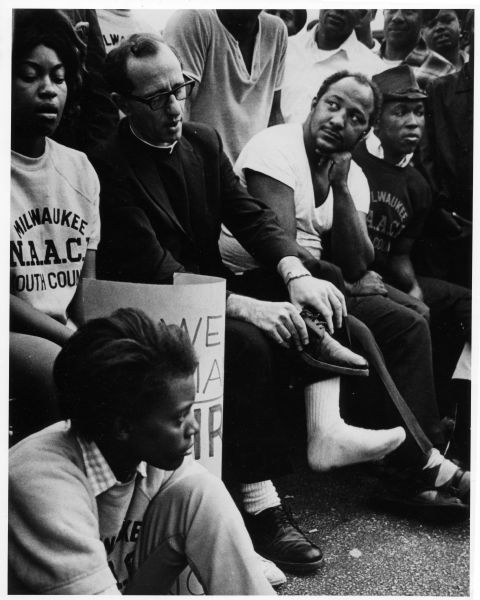

From his base at St. Boniface Church, Groppi affiliated himself with the local branch of the NAACP and became the chaplain to the Youth Group. Moreover, by 1964 he had joined forces with local attorney Lloyd Barbee, who had been demanding significant reforms in the public schools that served the African American community. In 1966, Groppi led protests against the white-only Eagle’s Club, a local fraternal organization, especially the membership of prominent Catholic jurist, Robert Cannon. When Cannon refused to resign from the Eagle’s, Groppi led marchers to the judge’s home in Wauwatosa.[3]

Groppi’s most extensive crusade in Milwaukee was the quest for open housing. He worked with Councilwoman Vel Phillips in her fight for a city ordinance insuring equal access to housing. Mayor Henry Maier stubbornly opposed this measure, forcing Groppi to organize a public march across the 16th Street viaduct on August 28, 1967. Groppi and his fellow marchers walked to Kosciuszko Park, walking through a gauntlet of nearly several hundred hostile Milwaukeeans who hurled cherry bombs, bricks, bottles, feces and urine at the demonstrators. Groppi himself received death threats and saw himself hanged in effigy. The daily marches continued for two hundred days into early 1968, drawing thousands of people near and far. In 1968, a new federal Civil Rights law was passed that included long-desired language regarding housing discrimination.[4]

After 1968, Father Groppi began to fade from the scene. In 1970, he moved from St. Boniface to St. Michael’s Church but kept up a program of activism on other fronts. He even tried to go to law school. However, Groppi and many others who had been in the midst of the civil rights fray developed doubts about their future as Catholic priests. In 1976, he married Margaret Rozga in a civil ceremony in Las Vegas and later became a local bus driver as well as, for a time, the head of the Bus Driver’s Union. James Groppi died of brain cancer on November 4, 1985 and was buried in Milwaukee’s Mount Olivet Cemetery after a funeral at St. Leo Church in Milwaukee.[5]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Steven M. Avella, Confidence and Crisis (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2014), chapter five; Patrick D. Jones, The Selma of the North (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 93-95.

- ^ Avella, Confidence and Crisis, 115-121; Jones, Selma of the North, 95-99.

- ^ Avella, Confidence and Crisis, 121-32; Jones, Selma of the North, 100-102, 106-107, chapter five.

- ^ Avella, Confidence and Crisis, 135-45; Jones, Selma of the North, chapter seven.

- ^ Avella, Confidence and Crisis, 145-48.

For Further Reading

Avella, Steven M. Confidence and Crisis. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2014.

Jones, Patrick D. The Selma of the North. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.