Halyard Park is often referred to as a “suburb within a city.” Despite major changes to the physical landscape caused by freeway construction and urban renewal, Halyard Park is one of the longest-standing, black, middle-class, residential neighborhoods within Bronzeville.[1] It is located between Interstate 43, North Avenue, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, and Walnut Street. It is named for bankers and activists Ardie Clark Halyard and her husband Wilbur, who sponsored the neighborhood’s redevelopment in the 1970s.

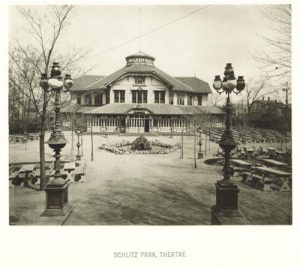

The neighborhood was first settled in the mid-1800s. Much like many other neighborhoods in Milwaukee at the time, German immigrants predominated. A wide variety of industry developed nearby on the banks of the Milwaukee River, such as shoe factories, mills, and Schlitz Brewery. Walnut Street grew to be the area’s commercial heart.[2]

By the early 1900s, the original German families began leaving the area. In their place came Hungarians, Italians, Poles, African-Americans, and Eastern European Jews. By the 1930s, African-Americans predominated. The Abraham Lincoln House, once a Jewish community center, became the headquarters for the Milwaukee Urban League. In 1956, Lapham Park was renamed for George Washington Carver.[3]

The mid-1960s saw physical disruptions of the Halyard Park area. Interstate 43 was built right through the heart of Halyard Park, taking about a block of houses with it. Walnut Street was widened, hurting local business. In 1964, many blocks of dilapidated housing were torn down to create space for the Lapham Park Housing project, which consisted of 170 units of multi-family housing as well as a high rise for senior citizens.[4]

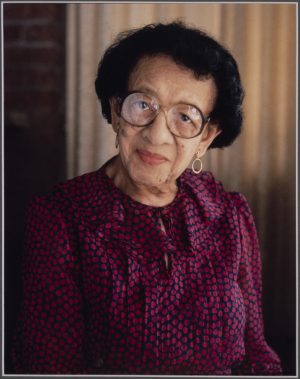

The mid-1970s ushered in further renewal efforts for the area. The United Realty Group, Inc., led by Beechie O. Brooks, broke ground for the Halyard Park subdivision on November 5, 1976. They purchased land from the Redevelopment Authority of the City of Milwaukee with the plan to build a subdivision with ranch houses valued from $40,000 to $75,000.[5] Ardie and Wilbur Halyard’s Columbia Savings and Loan Association financed the neighborhood’s first homes.[6] The Halyards, who came to Milwaukee in 1923 with the goal of improving housing for African Americans, founded Columbia Savings and Loan Association in 1924 to realize that mission.[7] Halyard Park was meant to be a working-class neighborhood. Most of the eventual residents worked for companies such as A.O. Smith and Master Lock.[8] Prospective residents had to prove not only that they could afford the house, but that they had the right vision for the neighborhood. In contrast to other neighborhoods with high population turnover, Halyard Park’s residents stayed. Between 1976 and 1997, there were only two resales. While many neighborhoods around Milwaukee declined in value in that period, Halyard Park’s homes increased.[9]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Michele Derus, “Halyard Park Is an Island in a River of Asphalt.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, September 16, 1997.

- ^ John Gurda, Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods (Milwaukee, WI: Historic Milwaukee, Inc., 2015), 199.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 199-200; Carver Park, Wisconsin Parks Exploration Project website, last accessed November 14, 2018.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 201.

- ^ “Halyard Park Ground Broken,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 13, 1976.

- ^ Fran Bauer, “A Suburban Oasis in Inner City,” Milwaukee Journal, August 27, 1986.

- ^ Ruth Edmonds Hill, Black Women Oral History Project Volume 5 (Westport, CT: Meckler Publishing, 1991), 4-5. For more on the Halyards, see Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-45 (Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 87-92.

- ^ Derus, “Halyard Park Is an Island in a River of Asphalt.”

- ^ Derus, “Halyard Park Is an Island in a River of Asphalt.”

For Further Reading

Gurda, John. Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods. Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee Inc., 2015.

Hill, Ruth Edmonds, Black Women Oral History Project Volume 5. Westport, CT: Meckler Publishing., 1991.

See Also

Explore More [+]

Understory

Milwaukee’s Neighborhoods: Not Only a Question of Where, but When

Milwaukee is often affectionately known as the “City of Neighborhoods.” To reflect this moniker, the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee (EMKE) features a number of entries on these diverse communities that form integral parts of the city’s larger whole. Some neighborhoods are identified by a landmark structure or style of homes, like the historic lighthouse in the North Point neighborhood or the Arts and Crafts bungalows of Washington Heights. Others, like Bronzeville, are defined by their complex history, cultural atmosphere, and community activism.

As the image researcher for EMKE, I am responsible for identifying maps, photographs, and other materials to illustrate our entries. This task is both challenging and rewarding. I frequently rely on photographs of streetscapes or historic buildings to visually represent Milwaukee’s neighborhoods. But neighborhoods are not static, nor are their boundaries. As a result, a photograph of something as solid as a building turns out to have a much more fluid neighborhood identification than I previously thought.

The Frederick Ketter Warehouse is a prime example of how murky a building’s place in Milwaukee can be, even after standing on the same plot of land for over one hundred years. The Ketter Warehouse, built around 1891 as a grocery warehouse for Milwaukee resident Frederick Ketter, is located one block west of N. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive at 325 W. Vine Street. Over the course of its history, it has been used for a variety of small business and manufacturing enterprises, most notably as the Walter Geiger Horseradish Factory that operated from 1936 to 1945. If you were to enter the Ketter Warehouse’s address into Google Maps today, you would find that it is located on the eastern edge of—but undoubtedly within—the neighborhood boundaries of Halyard Park.[1] But this was not always the case.

The Ketter Warehouse was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982 in order to preserve its Romanesque Revival architecture and German Renaissance styling; these architectural details provide insight into Milwaukee’s ethnic demographics and development at the end of the nineteenth century.[2] The local group responsible for generating this nomination was not Halyard Park, but members of Historic Brewer’s Hill. The Ketter Warehouse was even listed in a Home and Garden tour published by the Historic Brewer’s Hill Neighborhood Association in 1998.[3] Brewer’s Hill is a neighborhood known for its local commitment to historic preservation and restoration. It is located just the east of Halyard Park. Today, N. MLK Drive is generally recognized as the boundary between Halyard Park and Brewer’s Hill. To which neighborhood does this building then belong? Halyard Park, where today’s accepted boundaries place it, or Brewer’s Hill, where it has been historically claimed and recognized?

Making this determination and deciding with which entry to include the image of the Ketter Warehouse was not an easy one. Buildings are valuable to neighborhood communities; they help establish a sense of place, identity, and pride. Ultimately, we have chosen to feature the image alongside our Brewer’s Hill entry because primary source evidence helps us see that Milwaukee’s neighborhood boundaries have changed over time. Yet, it was also important that we acknowledge Halyard Park’s claim to the building in the image caption as well. The Halyard Park entry features half a dozen images of important places and people within that neighborhood.

The Encyclopedia of Milwaukee is a project that is historical in nature, and writing history is not necessarily about determining what the one correct answer may be. More often, it is about starting a dialogue and promoting greater understanding of how nuanced and complicated the past truly is, including something as seemingly simple as a grocery warehouse from 1891.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Google Maps, last accessed July 19, 2019.

- ^ “Frederick Ketter Warehouse,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Historic Brewer’s Hill, Milwaukee, 1982, last accessed July 19, 2019.

- ^ Historic Brewer’s Hill Neighborhood Association, “Historic Brewer’s Hill Home and Garden Tour” (1998), 12, last accessed July 19, 2019.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.