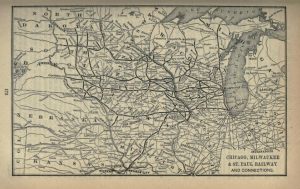

The Milwaukee Road, incorporated in 1847 as the Milwaukee & Waukesha Railroad Company, operated a 10,200-mile system stretching from the Midwest to the Pacific Northwest into the 1970s.[1] Its accomplishments included the first tracks connecting Lake Michigan at Milwaukee with the Mississippi River; high-speed, luxurious, beautifully designed Hiawatha passenger trains; efficient freight services; an innovative shop in Milwaukee; and a skilled workforce. The workers kept the railroad running until 1985.

The railroad always maintained close ties to the city of Milwaukee. The company was known informally for many years as “The Milwaukee Road” before the name was adopted as a trademark in 1953.[2] Some traditions endured. The railroad never changed the name of its junction known as Grand Avenue, even after the street was renamed Wisconsin Avenue in 1926.

The railroad’s early history was full of reorganizations and name changes. The Milwaukee & Waukesha turned into the Milwaukee & Mississippi Rail Road Company when it opened tracks to the Mississippi River in 1857, and then into the Milwaukee & Prairie du Chien Railroad Company. The LaCrosse & Milwaukee Railroad Company completed a second route to the river in 1858. Alexander Mitchell, a prominent Milwaukee banker, in 1863 organized the Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, which succeeded the La Crosse & Milwaukee, took over the Prairie du Chien line in 1867, and unified many Wisconsin railroads. After opening a line to Chicago, the railroad added Chicago to its name in 1874.[3] The general offices moved to Chicago in 1890. Growth continued in Iowa, Minnesota, Michigan, and South Dakota. A major extension to Puget Sound was completed in 1909.

For years, the railroad was a mainstay for the Milwaukee economy. By the early 1900s, it was the largest employer in the city, with 5,500 people on its payroll.[4] Addressing the Milwaukee Association of Commerce in 1927, Harry E. Byram, chairman of the board, explained that the railroad employed nearly 8,000 people in Milwaukee, paying them $12,500,000 annually—which he said was the largest payroll of any single industry in the city.[5]

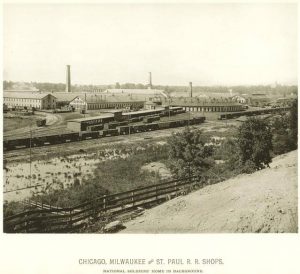

The massive West Milwaukee Shops buildings with tall smokestacks dominated the skyline of the Menomonee Valley for years. Between the opening in 1880[6] and 1938, shop crews built almost 700 steam locomotives.

When the shops were opened, workers complained about the distance from the city center. Merrill Park, a neighborhood for shop workers, developed nearby. It was named for Sherburn S. Merrill, the railroad’s general manager. In 1883, when 1,200 people worked at the shops, Merrill Park functioned as a separate community.[7]

The shops were known for innovative work under the leadership of Karl F. Nystrom (1881-1961), its chief mechanical officer.[8] While other railroads purchased passenger and freight cars from established builders, the Milwaukee Road constructed its own cars in its own shops. Nystrom held about one hundred patents for car construction and was especially well known for developing and building smooth-riding passenger car trucks[9] and welded, lightweight boxcars.

In a three-part series in 1947, the Milwaukee Magazine traced the history of the shops, which occupied 160 acres. About 3,500 worked there then, representing a dozen different crafts, not including yard and terminal personnel in the shops area.[10] Employment declined to about nine hundred in the late 1970s and further to 225 in 1983. Another sixty workers lost their jobs when the diesel house closed.[11]

Production under Soo Line ownership ended late in October 1986. The wheel shop was the last shop to operate. Edward J. Werner, its supervisor, turned out the lights when he left at the end of the day, December 23, 1986, closing it permanently.[12]

Milwaukee Road main and branch lines, served by a large freight classification yard in the Menomonee Valley, provided efficient freight service and regional marketing and distribution systems. In 1963, the Milwaukee inaugurated the XL Special and Thunderhawk freights, for a short time the fastest between Chicago, Milwaukee, and the Pacific Northwest.

Early views of the railroad in Milwaukee come from Henry H. Bennett (1843-1908), the Kilbourn City (now Wisconsin Dells) photographer known for his stereographs promoting railroad travel to the Dells and scenic locations along the Mississippi River.[13] Harvey R. Uecker (1900-1994) was a long time shops photographer. A portrait of the darker days comes from Lina Bertucci, who photographed her fellow workers beginning in 1974 while she worked as a brakeman (and also studied at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee). Her photos are “a record of a time when the legacy of railroading was still an integral part of American life but when signs of its neglect had begun to appear,” she wrote in the introduction to Railroad Voices.[14]

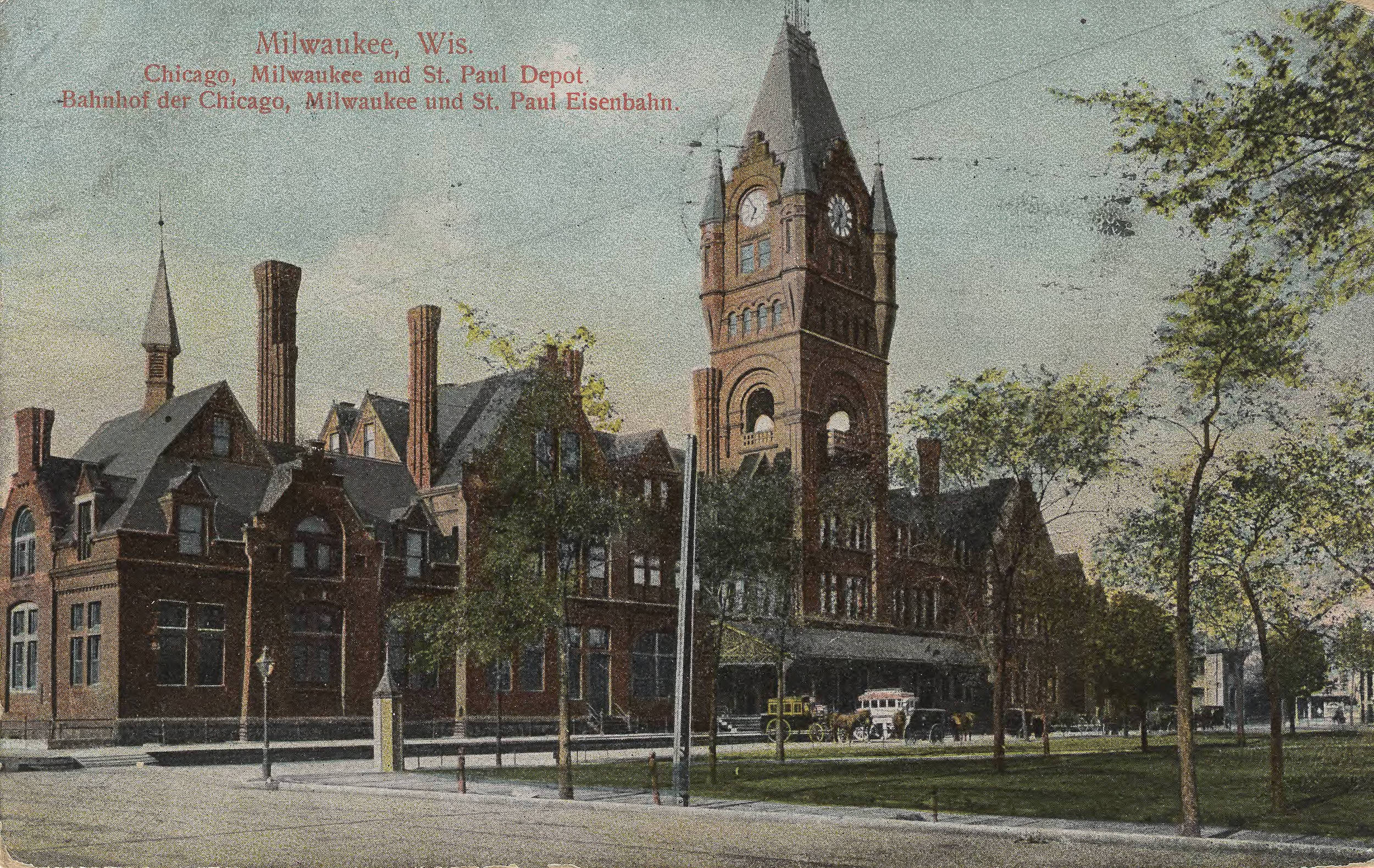

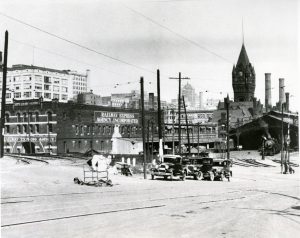

The railroad opened a magnificent station with a 140-foot-high clock tower at 317 West Everett Street in 1886. It was designed by architect Edward Townsend Mix. With alterations, it served until it was replaced in 1965. From 1966 to 1971, the new building at 433 West St. Paul Avenue also served the Chicago & North Western passenger trains. Remodeled in 2007, it remains in use as a railroad and bus terminal.

The railroad created a Milwaukee Terminal Division in 1892 because of the increasing volume of its Milwaukee business.[15] In a report for 1959 about its operating divisions, the railroad listed these statistics for the Milwaukee area: 25 miles of track, 3,297 employees, and 205,045 switching hours.[16]

The Milwaukee Road filed for bankruptcy three times in the twentieth century. In the first, from 1925 to 1928, its name changed from Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway to Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad. Its last, in 1977, led to the end of its corporate existence on December 31, 1985 and its merger with the Soo Line.

Workers kept the railroad running in all kinds of weather. They included such people as Soda Ash Johnny, John M. Horan, (1838-1938), Milwaukee, who worked almost 83 years;[17] Hugh McManus, Milwaukee (1869-1953), locomotive engineer of the first Hiawatha out of Chicago; Ron Morales, Milwaukee (1948-2002), Hispanic locomotive engineer; Herbert Wright, Chicago (1905-1990), dining car chef; and Lina Bertucci (the photographer), Karina Bertucci, and Cindy Angelos, women brakemen all from Milwaukee. The railroad’s legacy comes not from its buildings, but from the railroad families living today in Milwaukee.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Moody’s Transportation Manual (New York: Moody’s Investors Service, 1974) lists the mileage operated on December 31, 1973, as 10,297.

- ^ “Sign of the Times, the Story of the Milwaukee Road Trademark,” Milwaukee Road Magazine, April 1974.

- ^ Jim Scribbins, “Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad,” in Encyclopedia of American Railroads (Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 2007), 224-227.

- ^ John Gurda, The West End (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Humanities Program, 1980), 27.

- ^ H. E. Byram, “The City of Milwaukee and the Milwaukee Road” Milwaukee Magazine (March 1927), 3-4.

- ^ “Railroad Notes,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 14, 1880, p. 8.

- ^ “West Milwaukee, Milwaukee Sentinel, February14, 1883, p 8.

- ^ “K. F. Nystrom, Builder of the Hiawathas,” Milwaukee Road Magazine (July 1947), 7, 11-12; and “Karl Fritjof Nysrom, D.Eng.,” Railway Mechanical Engineer (March 1942), 93-99.

- ^ “Milwaukee High-Speed Passenger Trucks,” Railway Age (January 13, 1945), 146-148.

- ^ “Milwaukee Shops, the Story of the Road Car and Locomotive Shops in Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Magazine (May 1947), 4-8, 21; Milwaukee Magazine (June 1947), 12-16; Milwaukee Magazine (July 1947), 8-11. Statistics are in the July issue, p. 8.

- ^ Lawrence Sussman, “Sidetracked, Plan Cuts Some Ties Between City and the Railroad Named for It,” Milwaukee Journal, May 15, 1983.

- ^ “Milwaukee Shops,” email from Edward J. Werner to Thomas N. Tancula, May 7, 1999.

- ^ John Gruber, “Bennett Builds Railroad’s Image,” in Railroad Heritage 2 (2000): 8-11.

- ^ Linda Niemann and Lina Bertucci, Railroad Voices, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998), p. x.

- ^ “Under One Control,” Milwaukee Journal, July 13 1892.

- ^ “Milwaukee Road’s Operating Divisions,” Milwaukee Road Magazine (March-April 1960), 6.

- ^ “Horan Is Dead after He Notes 100th Birthday,” Milwaukee Journal, February 4, 1938, p. 1.

For Further Reading

Derleth, August. The Milwaukee Road, Its First Hundred Years. New York, NY: Creative Age Press, 1948, and Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 2002.

Kelley, John P. Railroads of Milwaukee. Forest Park, IL: Heimburger House Publishing Co., 2015.

Milwaukee Road Archives, Milwaukee Public Library.

Murray Tom. The Milwaukee Road. St. Paul, MN: MBI, 2005.

Scribbins, Jim. Milwaukee Road in its Hometown. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Publishing Co., 1998.

Scribbins, Jim. Milwaukee Road Remembered. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Publishing Co., 1990.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.