Until its corporate death in 1995, the Chicago & North Western Railway (C&NW) had long served greater Milwaukee. Although the Milwaukee & Mississippi Railroad was the first carrier to appear in the area, in the early 1850’s a predecessor of the Milwaukee Road, two future units of the C&NW, the Illinois Parallel Railroad, and the Green Bay, Milwaukee & Chicago Railroad, forged the eighty-five-mile link between Chicago and Milwaukee. These pioneer pikes consolidated in 1863 to form the Chicago & Milwaukee Railway (C&M). Three years later the C&NW, which dates from 1859, leased the C&M, and in 1881 the property officially joined the railroad. This corridor gave the C&NW a route that competed directly with arch-rival Milwaukee Road (Chicago, Milwaukee, & St. Paul Railway).[1]

The C&NW continued to increase its presence in Milwaukee. In 1882 the company built between Milwaukee and Madison, and in 1893 it acquired the 757-mile Milwaukee, Lake Shore & Western Railway, achieving direct connections to Ashland, the pineries of Wisconsin’s north woods, and the Gogebic iron range. Then in 1910-1911 the C&NW, under the banner of its Milwaukee, Sparta & North Western Railway subsidiary, constructed the 135-mile “Adams Cut Off” between Lindwerm, eight miles north of Milwaukee, and Sparta, establishing a high-speed line between Chicago, Milwaukee, and the Twin Cities. Soon thereafter the C&NW installed an eight-mile freight belt line between Butler and Milwaukee. By World War I the company operated nearly 10,000 miles of lines, making it one of America’s largest railroads.[2]

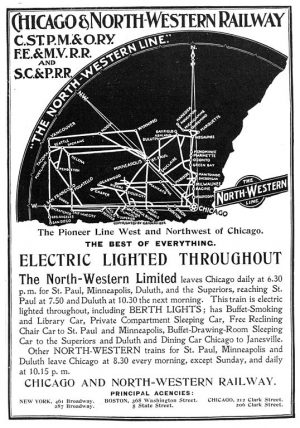

An historically wealthy railroad, the C&NW embraced its “The Best of Everything” motto. And residents of Milwaukee benefitted. In 1889 the company opened its massive Romanesque-style station designed by architects Charles Frost and Alfred Hoyt Granger at the end of East Wisconsin Avenue.[3] For decades this lakeside facility, dominated by its clock tower, served as a city landmark. And in the early years of the twentieth century, the C&NW spent heavily on elevated rights-of-way to keep its tracks away from busy city streets.

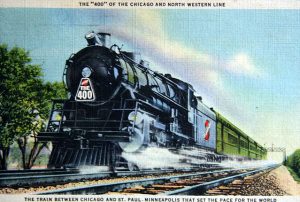

As part of its superb passenger operations, the C&NW operated scores of trains that took riders to such destinations as Chicago, the Twin Cities, Rapid City, and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Between 1930 and 1933 the company and the Kohler Aviation Corporation operated a joint service between Milwaukee and Grand Rapids, Michigan, with Kohler planes flying the distance. Although the Great Depression threw the C&NW into receivership, the railroad in 1935 introduced its most famous trains of the twentieth century, “The 400s.” Originally steam powered before dieselization in 1939, this initial service whisked passengers between Chicago-Milwaukee-Twin Cities in approximately 400 minutes. Later, other 400s appeared, including the Flambeau 400 and the Peninsula 400.[4]

Following the hectic years of World War II and its emergence from bankruptcy, the C&NW began to reduce its Milwaukee passenger service, slashing it drastically after 1956. Automobile competition, high labor costs, and over-regulation prompted the Ben Heineman administration in 1972 to “spin off” ownership of the railroad to its employees. The C&NW remained solvent, bolstered by Wyoming coal traffic. But the Union Pacific Corporation wanted key components, especially trackage from Nebraska connections to Chicago, and so in 1995 it acquired the property.[5]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ H. Roger Grant, “Chicago & North Western Railway Co.,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, edited by Janice L. Reiff, Ann Durkin Keating, and James R. Grossman, accessed August 15, 2015; Chicago and North Western Railway Company, Yesterday and To-day: A History (Chicago, IL: Press of Rand, McNally, 1905), 104 and 193, accessed August 15, 2015 via Google Books; James P. Kaysen, The Railroads of Wisconsin, 1827-1937 (Boston, MA: The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society, 1937), 15. Online facsimile at http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/search.asp?id=63 and http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/tp/id/69962, accessed August 15, 2015.

- ^ Kaysen, The Railroads of Wisconsin, 9, 10, 12; Tom Murray, Chicago & North Western Railway (Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press, 2008), 39, accessed August 16, 2015 via Google Books; H. Roger Grant, The North Western: A History of the Chicago & North Western Railway System (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press. 1996), 89.

- ^ “Magnificent New Depot to Be Opened Next Tuesday,” Milwaukee Daily Journal, December 7, 1889.

- ^ Grant, The North Western, 149-159; Mark Wegman, American Passenger Trains and Locomotives Illustrated (Minneapolis, MN: MBI Publishing Company. 2008), 84, accessed August 16, 2015 via Google Books; Flambeau 400, American-Rails.com, accessed August 15, 2015; Fred Klein, “Chicago & North Western’s Flambeau 400, 1958-1971,” TrainWeb.org, accessed August 15, 2015; Peninsula 400, American-Rails.com, accessed August 15, 2015.

- ^ Grant, “Chicago & North Western Railway Co.,” accessed August 15, 2015.

For Further Reading

Casey, Robert J., and W. A. S. Douglas. Pioneer Railroad: The Story of the Chicago and North Western System (New York, NY: Whittlesay House, 1948).

Chicago and North Western Railway Company and Components to April 30, 1910 (Chicago, IL: Chicago & North Western Railway Company, 1910).

Grant, H. Roger. The North Western: A History of the Chicago & North Western Railway System (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1996).

Scribbins, Jim. The 400 Story: Chicago & North Western’s Premier Passenger Trains (Park Forest, IL: PTJ Publishing, 1982).

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.