The Milwaukee Bridge War of 1845 was the culmination of a decade-long sectional struggle for preeminence among the city’s early settlements. In 1818, Solomon Juneau initiated what would become, years later, Juneautown, in what is now the eastern part of downtown Milwaukee. Sixteen years later, Byron Kilbourn founded Kilbourntown to the west of the Milwaukee River while George Walker established Walker’s Point to the northwest of what was then the point at which the river entered Lake Michigan. Kilbourn sought to isolate Juneautown. He developed a street pattern that differed from the existing pattern in Juneautown (the legacy of which can be seen today in the angularity of bridges spanning the Milwaukee River), created an advertisement map that portrayed Juneautown as a barren wasteland, and constructed a bridge across the Menomonee River just west of Walker’s Point that directly connected Kilbourntown with the road to Chicago—thereby allowing travelers and freight to bypass the ferry service that ran between Walker’s Point and Juneautown. Nonetheless, Juneautown remained the most populated of the three settlements.[1]

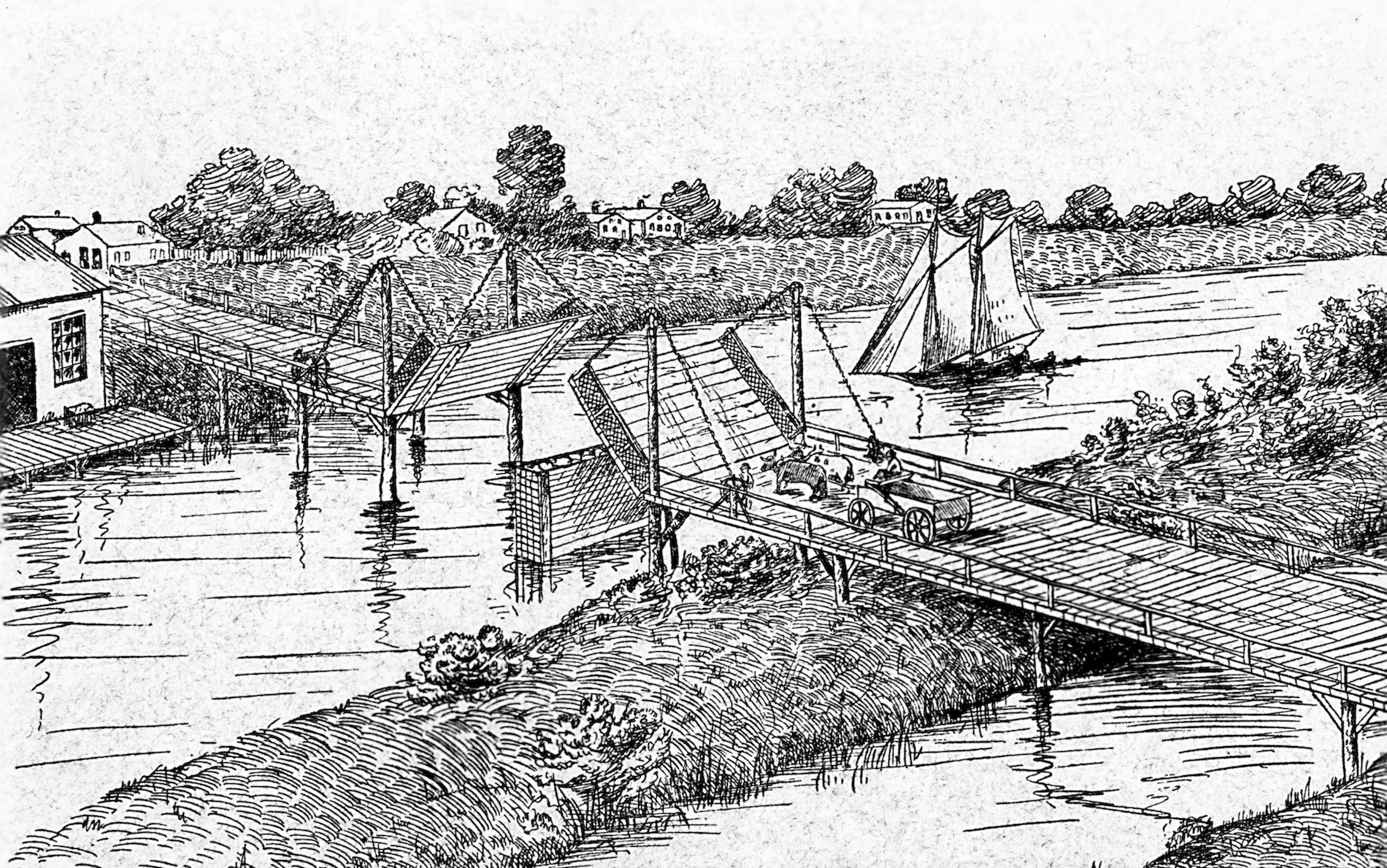

The Wisconsin territorial legislature united Juneautown and Kilbourntown into the Town of Milwaukee in 1839 (Walker’s Point would be added in early 1845), but each ward retained most of its autonomy. The following year, at the request of Juneautown, the legislature authorized construction of a drawbridge connecting Chestnut/Division streets (today’s Juneau Avenue, east and west of the river). Over the next four years, additional bridges were constructed at junctures of Oneida/Wells streets as well as Spring/Wisconsin streets. Finally, a crude, improvised bridge was built on Water Street that connected Juneautown with Walker’s Point. Kilbourn maintained that the bridges at Chestnut, Oneida, and Water streets interfered with river traffic and his ferry docks. The bridges were also poorly constructed—adding to the resentment of Kilbourntown settlers already annoyed over the taxes levied to build and maintain the Chestnut Street Bridge (the only one actually built with public funds). In truth however, East Siders bore the brunt of the cost of bridge maintenance.[2]

On May 3, 1845, a schooner ran into and partially wrecked the bridge at Spring Street (the structure that carried the most traffic and the only one whose construction Kilbourn had not actively opposed because it provided Kilbourntown settlers direct access to the post office and court house). Angered over the prospect of a special tax to repair the bridge, residents of Kilbourntown demanded that the Chestnut Bridge be declared a nuisance and dismantled. After the town trustees rejected a resolution to that end (by a 6 to 7 vote, with Kilbourn and Walker voting in favor), a West Side mob on May 8, first, tore down their side of the Chestnut Bridge and then damaged the Oneida Street Bridge, rendering both unusable. Aroused, East Siders aimed a cannon across the river at Kilbourn’s house, relenting in their plan to bombard it with clock weights only after being reminded that the household was in mourning over the death of Kilbourn’s daughter during the previous night.[3]

Alarmed by this lawlessness, town trustees passed a resolution imposing a $50 fine on anyone destroying a bridge. They also ordered, by a ten to one vote (with both Kilbourn and Walker voting in the affirmative) the reconstruction of the Chestnut Street Bridge and abandonment of the Oneida Street Bridge. East Siders were incensed, however, and on May 28, in an effort to isolate Kilbourntown, they sank the eastern half of the Spring Street Bridge into the river and destroyed the Menomonee River Bridge. Although people from both sides in the conflict were armed with weapons and some assaults were reported during the tense days following these incidents, there is no evidence of the “war” producing fatalities.[4] As bridge repairs were made, an uneasy truce ensued. In December, trustees applied to the legislature for a city charter and for authorization to rebuild and make more permanent the Spring Street Bridge, to erect a new bridge at Cherry Street, and to make needed improvements to the bridge at Walker’s Point.[5]

The Bridge War probably hastened support for the incorporation of the city, so that geographic rivalries might be lessened. In the referendum held on January 5, 1846 to approve of the proposed charter, however, sectional differences stood out in sharp relief. Voters in the West and South wards almost unanimously favored it, 461 to 8, whereas East Siders who feared bearing the brunt of taxation and remained bitter over bridge conflict were far more divided. They voted against the charter, 324 to 182. But with the incorporation of the city finalized on January 31, residents of both sides of the river came to accept bridge construction. On February 12, about sixty percent of voters in each of the two sections supported, in a referendum, the law mandating and financing the construction of the proposed new bridges, thus ending Milwaukee’s “Bridge War.”[6]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 15, 26-38, and 48-53; Robert W. Wells, This Is Milwaukee (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970), 48-49. For a capsule summary of the bridge conflict, see Matthew Prigge, “Bridge Wars!” Shepard Express, April 7, 2014, http://shepherdexpress.com/article-23073-bridge-wars_-a&e-shepherd-express.html, now available at https://shepherdexpress.com/arts-and-entertainment/ae-feature/bridge-wars/.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 49, 54; Wells, This Is Milwaukee, 49.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 54-55; Wells, This Is Milwaukee, 50-51; Goodwin Berquist and Paul C. Bowers, Jr., Byron Kilbourn and the Development of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 2001), 125; Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, May 9, 1845.

- ^ Wells, This Is Milwaukee, 51; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 55; Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, May 9, 1845; May 10, 1845; May 14, 1845; May 15, 1845; May 16, 1845; May 20, 1845; May 29, 1845. Gurda mistakenly lists the date of the mob action against the Spring Street Bridge as May 19. There are conflicting accounts concerning the second bridge destroyed. Gurda and the Sentinel indicate (correctly, the author concludes) that the Menomonee Bridge was rendered impassable whereas Wells writes that East Siders sank the north side of the Water Street Bridge.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 55-56; Wells, This Is Milwaukee, 51-52; Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, December 15, 1845; December 30, 1845; December 31, 1845.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 56-57; Wells, This Is Milwaukee, 52-53; Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, January 6, 1846; February 13, 1846; February 14, 1846. Under the act authorizing the bridge referendum, voting was limited to the east and west ward residents.

For Further Reading

Berquist, Goodwin, and Paul C. Bowers, Jr. Byron Kilbourn and the Development of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 2001.

Gurda, John. The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999.

Prigge, Matthew. “Bridge Wars!: What Our Crooked Bridges Reveal about Early Milwaukee.” Shepherd Express, April 7, 2014, http://shepherdexpress.com/article-23073-bridge-wars_-a&e-shepherd-express.html, now available at https://shepherdexpress.com/arts-and-entertainment/ae-feature/bridge-wars/.

Wells, Robert W. This Is Milwaukee. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.