Milwaukee is the birthplace of numerous writers and an inspiration for many others. Certain individuals are known primarily for their writing, whereas others made literary contributions in addition to the achievements in other walks of life for which they are best known. Some writers have achieved iconic status in the history of Milwaukee for their military or political service, and others have produced a vast canon of work. Milwaukee has inspired locals and outsiders alike to write novels, nonfiction, memoirs, and history for well over a century.

Historic Fiction

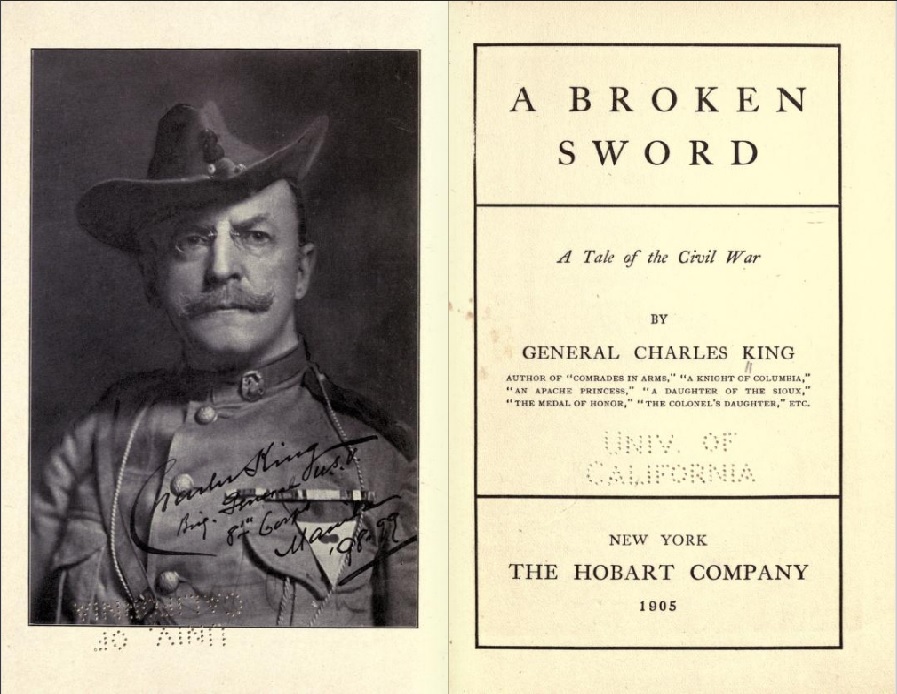

Charles King, born in 1844, grew up in Milwaukee and was best known as an army officer. He graduated from West Point in 1866 and served in the Fifth Cavalry throughout the American West. He then taught at the University of Wisconsin as well as several military schools. King served in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War and in the National Guard during World War I. Retiring in 1929, he lived out the remainder of his life in Milwaukee. Despite his celebrated military career, there was another side to King’s life—his writing. He wrote articles, short stories, serials, novels, nonfiction, and memoirs. One of King’s most famous memoirs, Memories of a Busy Life, describes the period of his life between West Point and the Philippines.[1] He penned more than sixty books, many of which told stories about the army and the American West.[2]

King’s novels follow similar plots: when a soldier is falsely accused, his lover turns on him. After he is wounded in battle, everyone sees the error of their ways, and his lover returns.[3] According to biographer John Bailey, he portrays a “factually accurate but romanticized picture of the frontier army.”[4] Although much of his writing is set during the Civil War, he dodges writing about slavery and uses racial epithets. Other groups are also described in a stereotypical fashion (e.g. Irish as alcoholics and women as beautiful caregivers).[5]

Like King, George W. Peck had two careers. He was a politician—most notably as mayor of Milwaukee and governor of Wisconsin. However, Peck may have been better known as a writer. He published a political-turned-humor magazine called the Sun, which began in La Crosse and moved to Milwaukee in 1878.[6] His most famous writing, though, is a series of humor stories, Peck’s Bad Boy, about a young troublemaker and his father. In these tales, the boisterous, wise boy typically tricks his dimwitted dad. While Peck writes candidly about Milwaukee’s citizens and neighborhoods, he only alludes to issues of race and class. Peck’s Bad Boy was made into a film starring Jackie Coogan in 1921.[7]

In contrast to King and Peck, Elizabeth Corbett’s primary vocation was writing. Although it does not explicitly mention Milwaukee, her memoir, Out at the Soldiers’ Home: A Memory Book, describes the twenty-five years during which she lived in the Northwestern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, the predecessor to the Veteran’s Administration, where her father worked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Published in 1941, Out at the Soldiers’ Home pays particular attention to the men who lived at the Home. While she recognizes their struggles with alcoholism, the tone of the book is primarily admiring and good-natured.[8]

In addition to her memoir, Corbett used Milwaukee as a setting for many of her novels. A prolific writer, Corbett ultimately published fifty books, some of which were made into films. Corbett based one of her characters, Mrs. Meigs, on Mrs. Purdon Wright, wife of the chaplain at the Soldier’s Home while Corbett lived there.[9] She adapted one of her Mrs. Meigs novels, Young Mrs. Meigs, into a play. Her other novels (some of which are set in Milwaukee), tended toward the commercial, and include: Cecily and the Wide World, Growing Up with the Grapers, She Was Carrie Eaton, Golden Grain, The Crossroads, and Sunday at Six.[10] Although Corbett was primarily a novelist, she wrote in a variety of genres. Her stories appeared in Century, Scribner’s, McCall’s, and Theater Guild Magazine. She published a biography of Ulysses S. Grant, and wrote poems and cartoons for the VA newsletter, The Tattler.[11]

While Peck’s Bad Boy and His Pa is one of the older representations of Milwaukee in fiction, there are many others that reference places, people, and communities. For example, William Henry Bishop’s 1887 novel, The Golden Justice, refers to a statue on top of Milwaukee’s old courthouse. Other writers, such as Charles K. Lush, reference prominent locals. One of the characters in Lush’s 1897 novel, The Federal Judge, was inspired by Henry Clay Payne, a Milwaukeean who served Theodore Roosevelt as Postmaster General. Edward Harris Heth’s Light Over Ruby Street (1940) is set in Milwaukee’s African-American community and concerns a mother’s desire for her daughter (who falls in love with a Black man) to pass as white.[12]

Contemporary Fiction

Three genres are prevalent in Milwaukee’s present-day fiction: mysteries; novels by and about women; and novels from the perspective of immigrants. Kathleen Anne Barrett, a Milwaukee native and graduate of Marquette University, wrote a cozy mystery series set in Milwaukee. The series features Beth Hartley, a murder-solving lawyer.[13] Titles include: Milwaukee Winters Can Be Murder, Milwaukee Summers Can Be Deadly, and Milwaukee Autumns Can Be Lethal. Another mystery writer, Lesley Kagen, grew up on the west side of Milwaukee and currently lives in Mequon. Whistling in the Dark, her national bestseller, is set in 1959 Milwaukee on the near west side in a familiar, if not exact, version of the neighborhood near Vliet Street. The plot involves a young girl negotiating absent family members while trying to protect her sister and solve a murder.[14] Its sequel, Good Graces, was published in 2011.

Girls in Peril (2006), by Karen Lee Boren, is also told from the perspectives of five friends in a Milwaukee suburb who experience a tragedy one summer in the 1970s. Boren grew up near Milwaukee and earned degrees in English from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.[15] Lauren Fox, another area resident, also sets her novels in Milwaukee. In Still Life with Husband (2007), a woman, reluctant to move to the suburbs and have a baby with her dull husband, begins an affair. Her second novel, Friends like Us (2012), focuses on what happens when a young woman’s two best friends fall in love with each other.[16]

Pauls Toutonghi’s 2006 novel, Red Weather, is set in the Third Ward in the late 1980s and follows the teenage son of Latvian immigrants, who are outraged when their son becomes a socialist.[17] Yvette in America (2000), by John Goulet, moves back and forth in time, following the memories of an immigrant woman as she lies dying in a hospital in Milwaukee.[18] Finally, Ayad Akhtar’s American Dervish (2012) is set in the eighties in Wisconsin and centers around a Pakistani boy studying the Quran with his mother’s friend, who begins dating a Jewish man.[19]

Nonfiction and Memoirs

Three themes emerge in much of Milwaukee’s nonfiction: reflections on political attitudes, the role of ethnicity, and career. Before Carl Sandburg became a famous poet, he lived in Milwaukee and was active in Milwaukee’s socialist movement. During this time, he produced a good deal of political writing, particularly regarding unsafe labor conditions.[20] After Sandburg moved to Milwaukee in 1909, he wrote prolifically: advertising copy (a seeming departure, given his anti-capitalist sentiments), essays, sketches, editorials, and poems. After a string of newspaper jobs, he became socialist mayor Emil Seidel’s secretary.[21] During this time, he defended the mayor by writing articles for the Social-Democratic Herald and for the pamphlet, Political Action.[22] After three short years in Milwaukee, Sandburg moved to Chicago in 1912 to work for a socialist newspaper.[23] He was not known as a poet until 1914, when he published in Poetry magazine, followed by The Chicago Poems in 1916.[24]

Golda Meir, who was born in the Ukraine but spent most of her childhood in Milwaukee before moving to Palestine in 1921, is better known as a founder and Prime Minister of Israel than as a writer. However, in 1962, she published This Is Our Strength: Selected Papers of Golda Meir (with a foreword by Eleanor Roosevelt). In the mid-1970s, she published two more books: A Land of Our Own: An Oral Autobiography and My Life. The former is a collection of Meir’s political speeches from 1930-1972. My Life is Meir’s autobiography, in which she discusses immigrating from Russia to Milwaukee. Although she invokes the poverty her family suffered and the difficulty her mother had in running the family’s store, Meir describes Milwaukee in unequivocally positive terms. She was so fond of the Fourth Street School (which went on to bear her name) that she returned to speak to students over fifty years later.[25]

Many other memoirs set in Milwaukee discuss immigration and ethnicity. In his 1939 memoir, The Log Book of a Young Immigrant, Laurence M. Larson discusses his status as a Norwegian immigrant in Milwaukee. He writes about teaching high school and describes the ethnicity of his students and neighbors. Larson notes the emphasis on learning German in public schools.[26] Similarly, novelist and playwright Edna Ferber, a reporter for the Journal newspaper who later wrote Show Boat and Giant, writes in A Peculiar Treasure (1939) that “The Milwaukee of that time was as German as Germany.”[27] However, the perception of Germans changed, as evidenced by Ernest Ludwig Meyer’s Bucket Boy: A Milwaukee Legend. This fiction/memoir hybrid about beer-drinking, newspaper-writing Germans was difficult to publish because of anti-German sentiment following World War II.[28] The “Bucket Boy” is an aging bookkeeper in a brewery (so called because he carries beer in pails, even as an adult).[29] In typical Milwaukee fashion, when asked whether newspapermen ever stopped drinking, Meyer replied, “sometimes, alas, they did stop, for under the constraints of brutal nature they occasionally, and with tremendous reluctance, went to sleep.”[30]

Some memoirists with roots in Milwaukee focused on their careers. Pat O’Brien, descended from Irish immigrants, writes about his acting career (with references to family roots in Waukesha and Milwaukee) in The Wind at My Back: The Life and Times of Pat O’Brien.[31] Horace Gregory, a poet, also writes about his life as an artist in The House on Jefferson Street: A Cycle of Memories.[32] Others write about childhoods in Milwaukee and subsequent careers as an academic (Howard Mumford Jones’s An Autobiography), a secret agent (Robert Murphy’s Diplomat among Warriors), and a diplomat (George F. Kennan’s Memoirs 1925-1950).[33] The pianist and Las Vegas showman Liberace grew up in Milwaukee and wrote several autobiographies: Liberace: An Autobiography (1973); The Things I Love (1977); and The Wonderful Private World of Liberace (1986). More recently, Kitty Kelley penned the unauthorized Oprah: A Biography (2011), in which she describes Oprah’s childhood in Milwaukee.[34] Although most of these writers left Milwaukee, their experiences in the city remained important to them.

Local Historians

One particular collaborative piece of nonfiction serves an important role in Milwaukee’s history. During the Depression, the federal government funded unemployed writers through the Works Progress Administration to write state guide books. The WPA Guide to Wisconsin: The Federal Writers’ Project Guide to 1930s Wisconsin was published in 1941 and includes sections specific to Milwaukee, including: transportation, points of interest, sports, theater, radio, and annual events. A brief introductory essay provides information on census data, safety, government, and industry.[35]

Milwaukee has also been home to several well-known local historians. William George Bruce worked in the newspaper industry and started the Bruce Publishing Company, which published books on religion, history, and technical subjects. Bruce wrote several memoirs and books on Milwaukee history, including The History of Milwaukee, City and County (1922)—three volumes of history, memoir, and biography—and A Short History of Milwaukee (1936). First serialized in the Wisconsin Magazine of History, his 1937 memoir, I Was Born in America, documents memories of childhood and family as well as Milwaukee citizens he encountered. He also founded the American School Board Journal to report on topics related to education.[36]

John Gurda is the most prominent writer on Milwaukee history. Born in Milwaukee, he earned an M.A. in Cultural Geography from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and has written more than twenty books on such topics as Milwaukee neighborhoods, local industries, and religion. His The Making of Milwaukee was the first full history of the city published since the late 1940s. This work was so successful that Milwaukee Public Television based an Emmy Award winning documentary on it in 2006.[37] Also noteworthy is Gurda’s, Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past, a 2007 collection of his monthly Journal Sentinel columns.[38] In the introduction, Gurda says, “Cream City Chronicles is a book of history as stories.”[39] Those stories explore many subjects, ranging from early pioneers to ethnic diversity and Lake Michigan, breweries, public education, and government. In other columns, Gurda provides histories of places (i.e. Cathedral Square and Mitchell Park Conservatory) and celebrations (i.e. Summerfest, the Wisconsin State Fair, and Milwaukee’s first Christmas tree).[40]

Milwaukee continues to make a distinct impression on writers, though the locus of that interest varies. Whereas some focus on immigrant communities or local politics, others use Milwaukee as a physical setting in fiction. Given Milwaukee’s robust history of producing writers, Milwaukee will undoubtedly be the subject of literature for years to come.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ The Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration, The WPA Guide to WI: The Federal Writers Project Guide to 1930s Wisconsin (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 1941), 143.

- ^ “Charles King, 1844-1933,” Autry National Center of the American West Library and Archives, accessed February 10, 2015.

- ^ John Bailey, The Life and Works of General Charles King 1844-1933 (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1998), 167-168.

- ^ Bailey, The Life and Works of General Charles King 1844-1933, 211.

- ^ Bailey, The Life and Works of General Charles King 1844-1933, 174, 211.

- ^ John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, WI, Vol. II (Chicago & Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1931), 1111.

- ^ Karen Kehoe, “Milwaukee’s Most Famous Teenager: Peck’s Bad Boy,” Children in Urban American Project, accessed April 20, 2015.

- ^ James Marten, foreword to Out at the Soldiers’ Home: A Memory Book, by Elizabeth Corbett (Skokie, IL: ACTA Publications, 1941), 12-15.

- ^ Marten, foreword, 13 and Laura J. Rinaldi and Jill Zahn, “A Belated Thank You to Miss Elizabeth Corbett,” in Out at the Soldiers’ Home: A Memory Book, by Elizabeth Corbett (Skokie, IL: ACTA Publications, 1941), 229.

- ^ Marten, foreword, 13.

- ^ Rinaldi and Zahn, “A Belated Thank You to Miss Elizabeth Corbett,” 229-232.

- ^ Harry Anderson, Milwaukee, At the Gathering of the Waters (Tulsa, OK: Continental Heritage Press, 1981), 168; Jessie Parkhurst Guzman, Vera Chandler-Foster, and William Hardin Hughes, “Negro Year Book: A Review of Events Affecting Negro Life, 1941-1946,” accessed April 20, 2015, https://books.google.com/books?id=yn50BgAAQBAJ&pg=PA660&lpg=PA660&dq=light+over+ruby+street+edward+heth+harris&source=bl&ots=r9WsaubEmA&sig=_4uJK_QsRAqRB6EybTy0-Mjup88&hl=en&sa=X&ei=P8I1VcmfLdPhoATLv4DYAg&ved=0CDUQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=light%20over%20ruby%20street%20edward%20heth%20harris&f=false, now available at https://books.google.com/books?id=BYMGAQAAIAAJ, accessed June 8, 2017.

- ^ Kathleen Anne Barrett, Milwaukee Autumns Can Be Lethal (New York: NY: Avalon Books/Thomas Bouregy & Company, Inc., 1998).

- ^ Lesley Kagan, Whistling in the Dark (New York, NY: New American Library/Penguin), 2007.

- ^ Karen Lee Boren. “About Karen Lee Boren,” accessed February 19, 2015. http://www.karenleeboren.com/about.html.

- ^ Lauren Fox, Friends like Us (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012).

- ^ Pauls Toutonghi, Red Weather (New York, NY: Shaye Areheart Books, 2006).

- ^ Maurice Kilwein Guevara, “‘Yvette in America’ by John Goulet,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 10, 2000, accessed February 19, 2015.

- ^ Ayad Akhtar, American Dervish (New York, NY: Back Bay Books/Little, Brown and Company, 2012).

- ^ Penelope Niven, Carl Sandburg: A Biography (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1991), 207.

- ^ Richard Crowder, Carl Sandburg (New York, NY: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1964), 42.

- ^ Niven, Carl Sandburg: A Biography, 216, 219, 227-229.

- ^ Crowder, Carl Sandburg, 15, 42-43.

- ^ “Carl Sandburg’s Biography: 1878-1967,” accessed April 20, 2915, http://carl-sandburg.com/biography.htm.

- ^ Golda Meir, My Life (New York, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1975), 32-35.

- ^ Laurence M. Larson, Log Book of a Young Immigrant (Northfield, MN: Norwegian-American Historical Association, 1939), 283-285.

- ^ Edna Ferber, A Peculiar Treasure (New York, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1939), 28, 132.

- ^ Karl E. Meyer, Introduction to Bucket Boy: A Milwaukee Legend (Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1947).

- ^ Ernest Ludwig Meyer, Bucket Boy: A Milwaukee Legend (Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1947), 1.

- ^ Ernest Ludwig Meyer, Preface to Bucket Boy: A Milwaukee Legend (Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1947).

- ^ Pat O’Brien, The Wind at My Back: The Life and Times of Pat O’Brien (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964).

- ^ Horace Gregory, The House on Jefferson Street: A Cycle of Memories (New York, Chicago, and San Francisco: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971).

- ^ Howard Mumford Jones, An Autobiography (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1979), 13;

- Robert Murphy, Diplomat among Warriors (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964); George F. Kennan, Memoirs 1925-1950 (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1967), 3-5.

- ^ Jackie Loohauis-Bennett, “Milwaukee Plays Supporting Role in Oprah Book,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 12, 2010, accessed April 20, 2015.

- ^ The Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration, The WPA Guide to Wisconsin: The Federal Writers’ Project Guide to 1930s Wisconsin (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2006 [1941]), 239-264.

- ^ “William George Bruce: A Family Heritage Resource,” accessed April 23, 2015.

- ^ John Gurda, One People, Many Paths: A History of Jewish Milwaukee (Menomonee Falls, WI: Burton & Mayer, 2009), Biographical Statement.

- ^ John Gurda, Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2007).

- ^ Gurda, Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past, xv.

- ^ Gurda, Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past, vii-xii.

For Further Reading

Anderson, Harry H. and Frederick I. Olson. Milwaukee at the Gathering of the Waters. Tulsa, OK: Continental Heritage Press, Inc., 1981.

Bailey, John. The Life and Works of General Charles King 1844-1933. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1998.

Corbett, Elizabeth. Out at the Soldier’s Home: A Memory Book. Skokie, IL: ACTA Publications, 1941 & 2008.

Crowder, Richard. Carl Sandburg. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1964.

Flower, Frank Abial. History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Chicago: The Western Historical Company, 1881.

Gregory, John G. History of Milwaukee, WI. Vol. II. Chicago & Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1931.

The Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration. The WPA Guide to Wisconsin: The Federal Writers’ Project Guide to 1930s Wisconsin. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 2006. First published 1941 by the Federal Writers’ Project.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.