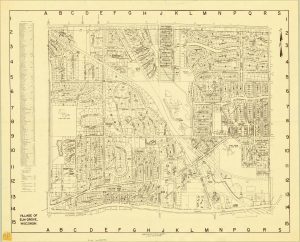

The Village of Elm Grove is a community of about six thousand people in eastern Waukesha County. It borders the Village of Wauwatosa to the east and the City of Brookfield in all other directions. It was part of the Town of Brookfield until 1955. It is governed by a seven-member volunteer board. All trustees, including the village president, are elected to two-year terms.[1] Elm Grove is part of the School District of Elmbrook and has an elementary school and a middle school.[2]

In 1836, Robert Curran became one of the first permanent white settlers in Elm Grove. Most early residents were German Catholics, and German Lutherans came in the 1840s. Elm Grove’s first post office opened in 1842. Then, in 1848, area residents began laying more than 650,000 white oak timbers and planks to build the fifty-eight-mile Watertown Plank Road to connect Milwaukee to Watertown. Toll gates were erected at regular intervals. The road remains the village’s main thoroughfare. Railroad tracks were laid in the 1850s. According to legend, the surrounding trees inspired the village’s name. A new depot was built in 1864. Other services typical of railroad stops such as a general store for residents, an inn and tavern for travelers, and a mill were also established.[3]

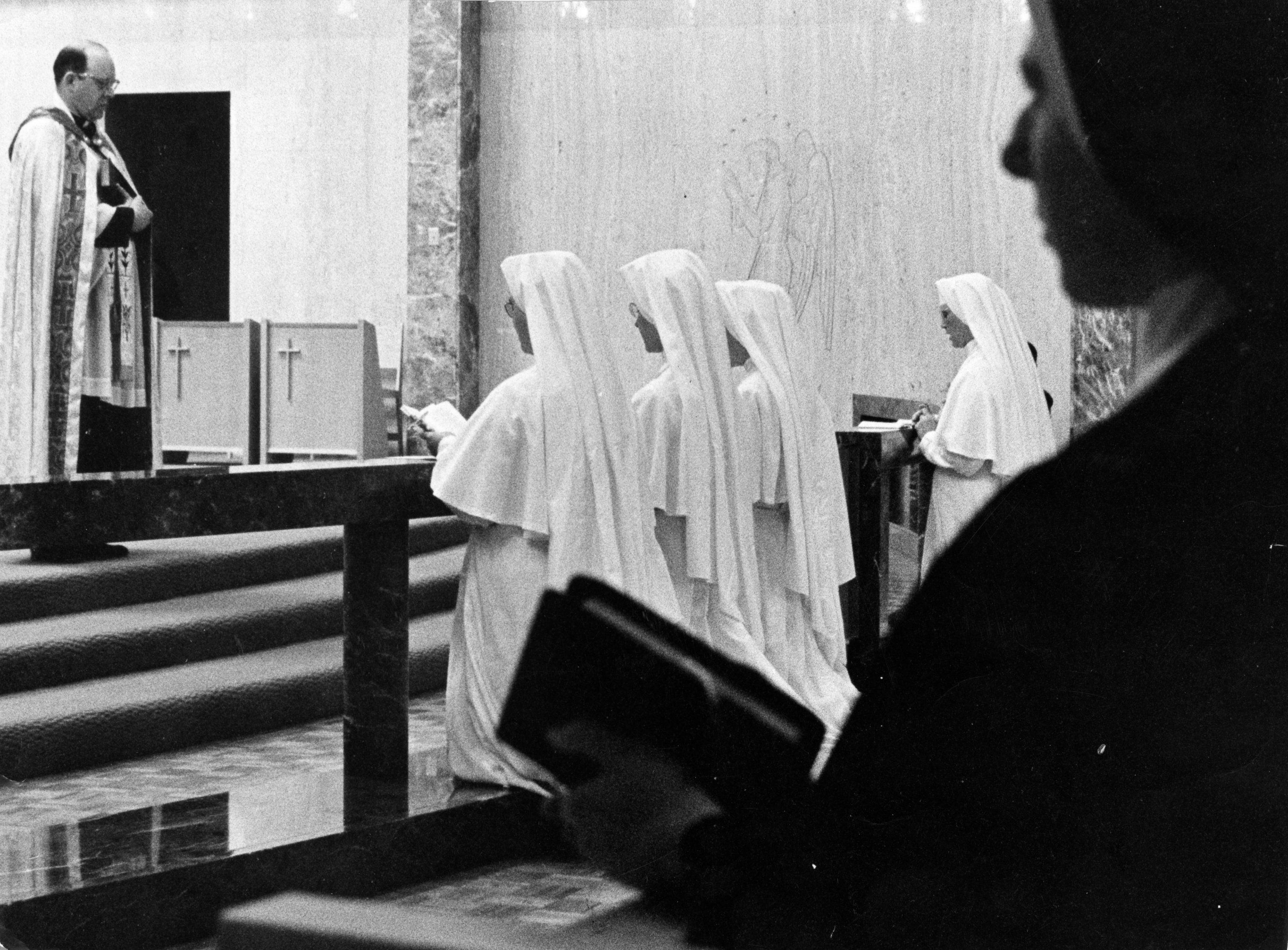

Roman Catholic institutions were prominent in Elm Grove’s history. Sixteen families organized St. Mary’s Parish, the Church of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, in 1848, and a church was erected in 1851. In 1855, a group of nuns led by Mother Caroline Friess of the School Sisters of Notre Dame traveled west on Watertown Plank Road in search of a suitable place to build a convent. According to the local story, the horse pulling their wagon indicated the spot to settle when he stopped and could not be convinced to move again. Mother Freiss subsequently purchased twenty acres of land for their convent, school, and orphanage. The orphanage closed in the 1940s, but the convent and school remained there in 2017. The sisters continue to do outreach work with at-risk youth in Milwaukee and aid in humanitarian efforts in Latin America.[4]

Elm Grove’s first twenty residential lots were platted in 1869. By 1880, Watertown Plank Road and the railroad had brought enough settlers that Elm Grove was considered an unincorporated community. In the 1920s and 1930s the automobile made it possible for people who worked in Milwaukee to move to Elm Grove. Then, finally, Elm Grove experienced rapid suburbanization during the Baby Boom after World War II. The village incorporated in 1955, at about the same time as the neighboring City of Brookfield. These defensive incorporations were part of the effort of Milwaukee’s suburbs to stave off absorption by the city. Elm Grove’s population was just shy of five thousand residents in 1960.[5]

Elm Grove’s zoning laws require houses to be built on large lots, which helps maintain a rural character, but also makes it difficult for low-income persons to live there. According to the U.S. Census, Elm Grove had about six thousand residents, and the median household income was $119,512 in 2016.[6] Elm Grove prides itself on a “small town” image with locally-owned businesses, civic organizations, and a neighborly feeling.[7]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ United States Census Bureau, “Elm Grove village, Wisconsin,” https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/ community_facts.xhtml, last accessed July 10, 2017; “Village Committees, Commissions and Boards,” Village of Elm Grove, Wisconsin website, last accessed July 10, 2017.

- ^ “Elmbrook Schools,” School District of Elmbrook website, last accessed July 10, 2017.

- ^ “History of Elm Grove Told by New Booklet,” Milwaukee Journal, November 12, 1959, 4: 15; History of Waukesha County, Wisconsin (Chicago, IL: Western Historical Company, 1880; reprint, Waukesha: Waukesha County Historical Society, 1976), 731; Mary J. Scheffel, “Elm Grove Keeps a Tranquil Beauty,” Milwaukee Journal, May 1, 1994; and “History of Elm Grove,” Village of Elm Grove, Wisconsin website, last accessed July 10, 2017.

- ^ “History of Elm Grove,” Village of Elm Grove, Wisconsin website, last accessed July 10, 2017; “Notre Dame of Elm Grove,” School Sisters of Notre Dame, Central Pacific Province website, last accessed July 10, 2017; and “Our History,” St. Mary’s Visitation website, last accessed July 10, 2017.

- ^ Scheffel, “Elm Grove Keeps a Tranquil Beauty,” and “History of Elm Grove,” Village of Elm Grove, Wisconsin website, last accessed July 10, 2017.

- ^ United States Census Bureau Quick Facts, last accessed March 9, 2018

- ^ United States Census Bureau Quick Facts, last accessed March 9, 2018; “Elm Grove in the 21st Century,” Village of Elm Grove, Wisconsin website, last accessed July 10, 2017.

For Further Reading

Bruhn, Marion and Patricia Basting, eds. The History/Landmark Tour of Brookfield and Elm Grove, Wisconsin. 5th ed. Brookfield, WI: Elmbrook Historical Society, 2007.

“History of Elm Grove Told by New Booklet.” Milwaukee Journal. November 12, 1959, 4: 15.

Ramstack, Thomas. Brookfield and Elm Grove. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

See Also

Explore More [+]

Understory

Uncovering Historical Inaccuracies

When Americans write local history, they often highlight the name of the first white settler as the founder of the area. In Southeastern Wisconsin, they also tend to mention the location of the first mill and maybe even a side street that used to be a plank road. These core pieces of information are generally the most well researched and well documented pieces of local history. Local historical societies and libraries are assumed to be the authority on this basic information. So, when I was asked to assess the validity of the first white settler named in a draft of the Village of Elm Grove entry, I was certainly surprised. It’s almost an assumed rule that such research had been done years ago by local historians. However, when embarking on a project with a scope as large as the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee (EMKE), exceptions to the rule are inevitable.

To fully follow this thread with me, it is first important to understand how entries in the Encyclopedia are processed after they are written and edited. All entries posted in the EMKE go through the process of fact-checking. To be brief, an editor reads the entry and highlights names, dates, or statistics that need to be verified. She then sends the highlighted document to a fact-checker to process. It is in this phase that one particularly challenging research task emerged. A problematic introductory line in a paragraph about the history of the Village of Elm Grove claimed that the first white settler was named William Howe and he had received a presidential land grant for what is now Brookfield and Elm Grove in 1820. Spot the problem? Land in what is now Brookfield and Elm Grove was not available for purchase until after the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, when the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Odawa ceded land west of Lake Michigan to the United States. In 1820 William Howe could not have been granted land that was not even available to be granted. The simple introductory sentence sparked a research task to locate the origin of a historical inaccuracy.

I began by analyzing the source the author of the entry used. The City of Brookfield website has a history tab, and it was here that the author obtained information about William Howe being the first white settler During the fact-checking process, this same website was used to confirm the claim about William Howe; while the information was not independently verified, we did know that the author did not misquote his source. With no footnotes or citations on the City website, it seemed like I had hit a dead end. Well not quite. More accurately, I found myself at the start of a new thread. One that would, as is common in historical research, lead me to more questions than answers. Not deterred by my failed mining of the Brookfield website, I began searching on the U.S Department of Land Management’s online database.[1] Complete with an interactive GIS map and intuitive queries, this database allows anyone with access to the internet the ability to search documentation associated with land plats in the United States down to the township, range, and section. The results of my search for Elm Grove and Brookfield? No William Howe. Nothing in what is now Elm Grove. Nothing in was is now the entire township of Brookfield. The earliest land patent that I could find was one granted in 1850 to Harvey Birchard, an early Milwaukee real estate agent, under the authority of the Land Act of 1820 (3 Stat. 566). Another dead end right? Wrong. What was revealing about this information was not just that William Howe’s name was nowhere to be found, but that land grants were noted with the year of the act that authorized the sale of that land. My first assumption after looking at the Land Management website was that William Howe may in fact have had land in the Brookfield Township, but maybe his land grant was signed much later and just under the authority of an 1820 law.

Since the Department of Land Management database could provide me with no other valuable information, I followed the thread closer to the source, to the Waukesha County Historical Society Archives. If a record of William Howe existed, it was going to be there. When I arrived for my research appointment, the archivists had prepared everything they could find on the first land grants for the Brookfield Township, and anything related to a “William Howe.” None of the sets of early land plat maps, compiled by local governments and previous local historians, listed William Howe as an early settler of the area, let alone the first. At this point, I assumed again this thread had also reached its end. I guessed that the City of Brookfield website must have been the source of this inaccuracy and it had made its way into a draft for the EMKE. But that was not the case.

With no definitive answer as to where, if at all, William Howe fit into the early history of Elm Grove, I turned my attention to the other documents that the archivists of the Waukesha County Historical Society had pulled for my research appointment. During the 1950s and early 1960s, researchers at the Waukesha County Historical Society compiled short biographies of all the early settlers of the area in a catalog called Pioneer Notebooks.[2] Among the names in this extensive catalog was one William Howe. The small faded page in the coil-bound booklet read:

Name: HOWE, WILLIAM

Township Settled: Brookfield Date: 1840s

Occupation: Farmer-Pioneer

Death: Date 1911 Place: Milwaukee, Wis.

Where Buried: Fair View Mausoleum

Items of Interest: Pioneer

Veteran of War of 1812. One of first land grants. Blue Mound to West Brookfield. Elm Grove to Moorland Roads. SW corner of Town of Brookfield. Was a prominent farmer in Elm Grove Section.

Based on this page it appeared that William Howe was indeed one of the earliest settlers of the area, albeit not quite as early as the Elm Grove entry claimed. But why did his name not appear on any of the early land plat maps? It turns out, this page was itself the victim of several historical errors. Basic math and knowledge of normal human lifespans suggest that the information on this page is questionable. Two dates on the document did not add up. If William Howe was a veteran of the War of 1812 and died in 1911, as the Waukesha County Pioneer claimed, he would have had to have been at least 117 years old on his deathbed. As if that wasn’t enough, I ran a search on Fair View Mausoleum and found that it had become decrepit and was razed in the 1990s.[3] All the individuals interred there were transferred to Graceland Cemetery, and the entire process was thoroughly documented; the documentation itself was eventually digitized by the Milwaukee Public Library. After scrolling through every single name on the list, I found no evidence of a William Howe ever being interred at Fair View Mausoleum. It turns out that I was closing in on the origin of the inaccuracy that ended up in the draft of the EMKE entry.

One of the last documents the archivists at the Waukesha County Historical Society showed me was a page from the 1959 Centennial Edition of the Waukesha Freeman. Inside this hardcover special print was a short piece about the construction of a new segment of Interstate 94 that passed through old farm land. And who supposedly used to own that farm land? William Howe, the veteran of the war of 1812 who died in 1911. That’s right, the short piece in the Waukesha Freeman was verbatim the same information as the handwritten biography in Pioneer Notebooks. The archivists and I concluded that the local historian who wrote up the brief biography of William Howe in the catalog must have copied the information from the short article in the local newspaper. Since the newspaper article had no source for where the information came from, my best guess is that it was the product of word of mouth and local lore. In the late 1950s, as the landscape in Wisconsin was drastically changing with the emergence of major freeway systems, an article that put farmland once owned by a founding settler in the path of construction and modernization would have been timely and widely read in the community. Apparently, it was widely enough read to inspire a local historian to copy the information into their institutional records. Records that likely were referenced by researchers compiling information for the City of Brookfield website. William Howe almost made his way into The Encyclopedia of Milwaukee through a thread of perpetuated historical inaccuracies that originated in a 1959 newspaper article.

While we assume that basic aspects of local history have been well researched, we must remember that there are always exceptions to the rule. History is dynamic, always being made, always being reassessed. If working for The Encyclopedia of Milwaukee has taught me anything, it’s that we cannot assume that core pieces of local history are set in stone. In fact, maybe it is time for local historical institutions to dust off their old plat maps and pioneer biographies and reassess what they think are historical facts.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “Land Catalog,” U.S. Department of Land Management, accessed January 18, 2019.

- ^ “Pioneer Notebooks Waukesha County, Wisconsin,” Waukesha County Museum, Waukesha, WI.

- ^ “City of Milwaukee, Department of City Development, Fairview Mausoleum,” Milwaukee Public Library,accessed January 18, 2019.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.