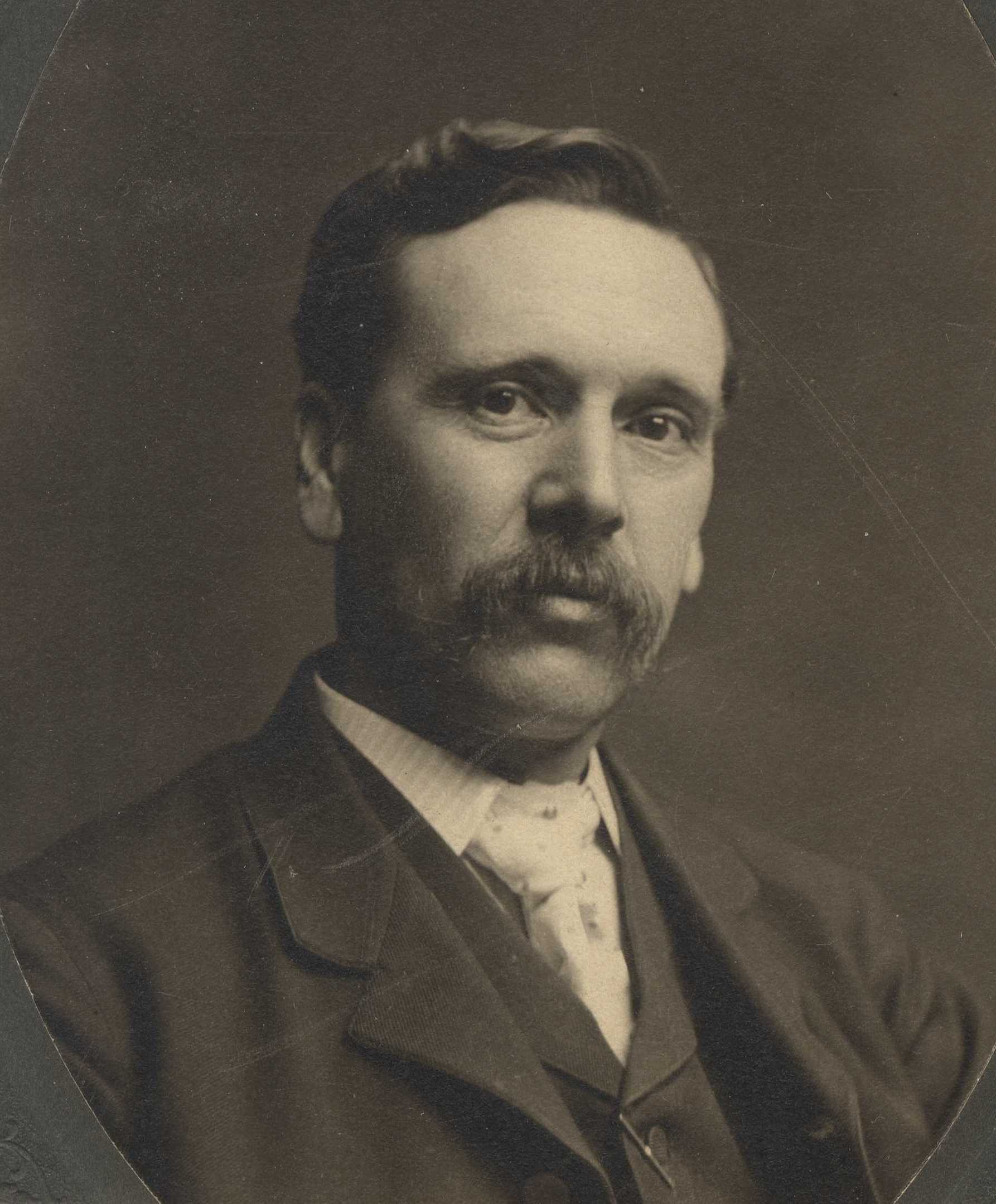

Charles B. Whitnall, planner and conservationist, is considered the main inspiration for Milwaukee County’s system of public parks and also an influential advocate of regional planning in early twentieth century Milwaukee.

Whitnall was born in 1859, four miles north of downtown, in present day Riverwest. Charles’s father, Frank Whitnall, was an English immigrant and gardener who operated a prominent retail seed and floral business, with greenhouses on the family property along the banks of the Milwaukee River and a busy downtown storefront location. Whitnall inherited his father’s business and was instrumental in the creation of the Florist Telegraph Delivery System, a service that eventually enabled the delivery of flowers over great distances.

Whitnall joined Milwaukee’s nascent Social Democratic party in the 1890s and was elected city treasurer as part of the Socialist sweep into city politics in 1910. Whitnall also served as a member of the Milwaukee County Park Commission from its inception in 1907 to 1941, and on the city of Milwaukee’s Board of Public Land Commissioners from 1907 to 1945. In these positions, he became a strong advocate for Garden City planning, which emphasized residential decentralization; clustered, village-like communities with close access to greenspace; and a rejection of the traditional urban grid pattern of streets. During the 1900s and 1910s, Whitnall published a series of writings that mused on the built environment and directly linked socialist ideas with city planning.[1]

In 1923, Whitnall published plans for a countywide system of parks and parkways that served as the foundation for the Milwaukee County Park System. Whitnall’s 1923 park plans were especially notable for their emphasis on combining together wetland protection, streambank restoration, flood control, and public recreation. He also imagined that new communities filled with residents from all walks of life would develop along and near the county’s new parks, thus furthering his Garden City-inspired planning ambitions. Whitnall also foresaw the growing importance of the automobile. He included eighty-four miles of “parkways” that ran along the natural contours of the landscape, an early example of making an accommodation to the automobile while maintaining conservation. Whitnall’s park plans were adopted by Milwaukee County officials with remarkably little revision, and land acquisition gradually moved ahead throughout the 1920s and 1930s.[2]

Whitnall’s influence also extended through his family. His son, Gordon, also became an influential planner, moving to Los Angeles and becoming a founding member of the Los Angeles City Planning Association in 1913; he was the Director of Planning for the city of Los Angeles from 1920 to 1930. Charles Whitnall died in 1949, at age 89. Whitnall Park and Whitnall Avenues are both named after him, and the original Whitnall family home remains at 1208 E. Locust Street.

Footnotes [+]

For Further Reading

McCarthy, John. Making Milwaukee Mightier: Planning and the Politics of Growth, 1910-1960. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009.

Platt, Lorne. “Planning Ideology and Geographic Thought in the Early Twentieth Century: Charles Whitnall’s Progressive Era Park Designs for Socialist Milwaukee” Journal of Urban History 36, no. 6 (2010): 771-791.

See Also

Explore More [+]

Understory

Charles Whitnall in Riverwest

One of the early residences just off today’s Humboldt Boulevard—at Locust Street—was that of florist Frank Whitnall, a Cream City brick residence now at 1208 E. Locust Street. Whitnall, who began building that house in 1851[1] near what was then the Humboldt Plank Road, had about twenty acres there, with extensive greenhouses growing plants for his downtown store. The property was referred to as Whitnall Knoll.[2]

Whitnall’s son Charles, born in that house in 1859, started out working in his father’s flower business and became nationally prominent in the industry.[3] But he went on to become one of the most important names in the history of Milwaukee parks and planning. A Socialist, Charles Whitnall served as city treasurer during the administration of Emil Seidel in 1910-12 and later organized the Commonwealth Mutual Savings Bank, a cooperative bank aimed at benefiting wage earners.[4]

According to John Gurda’s The Making of Milwaukee, Whitnall was a member of both the city’s Public Land Commission and the Milwaukee County Parks Commission, and was secretary of both bodies during the 1920s. He produced a master plan for parkways and parkland throughout Milwaukee County in 1923. Many of its elements became a reality,[5] giving Milwaukee a national reputation for its park system that lasted for many decades. In his later years, Charles Whitnall developed residential areas on some of his family’s Whitnall Knoll property, including houses on E. Roadsmeet Street near his childhood home, and the secluded Gordon Circle, at the east end of E. Burleigh Street.[6]

Footnotes [+]

- [1] Katherine Kaliszewski, “Socialism and City Planning: The Work of Charles Whitnall in Early Twentieth Century Milwaukee, Wisconsin” (MA thesis, Cornell University, 2013), 28.

- [2] Kaliszewski, “Socialism and City Planning,” 29.

- [3] John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 3rd ed. (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 2006; originally published 1999,), 268.

- [4] Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 268

- [5] Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 270.

- [6] Tom Tolan, Riverwest: A Community History (Milwaukee: Past Press, 2003), 19.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.