Over forty public libraries have been established in the Milwaukee metropolitan region since 1878, when the Milwaukee Public Library first opened its doors. Early library development in the region took place during the American Public Library Movement, which swept across much of the United States, including Wisconsin, in the late 19th through the early 20th century. Later public library development has occurred since 1950, as population centers grew and more communities built their own libraries.

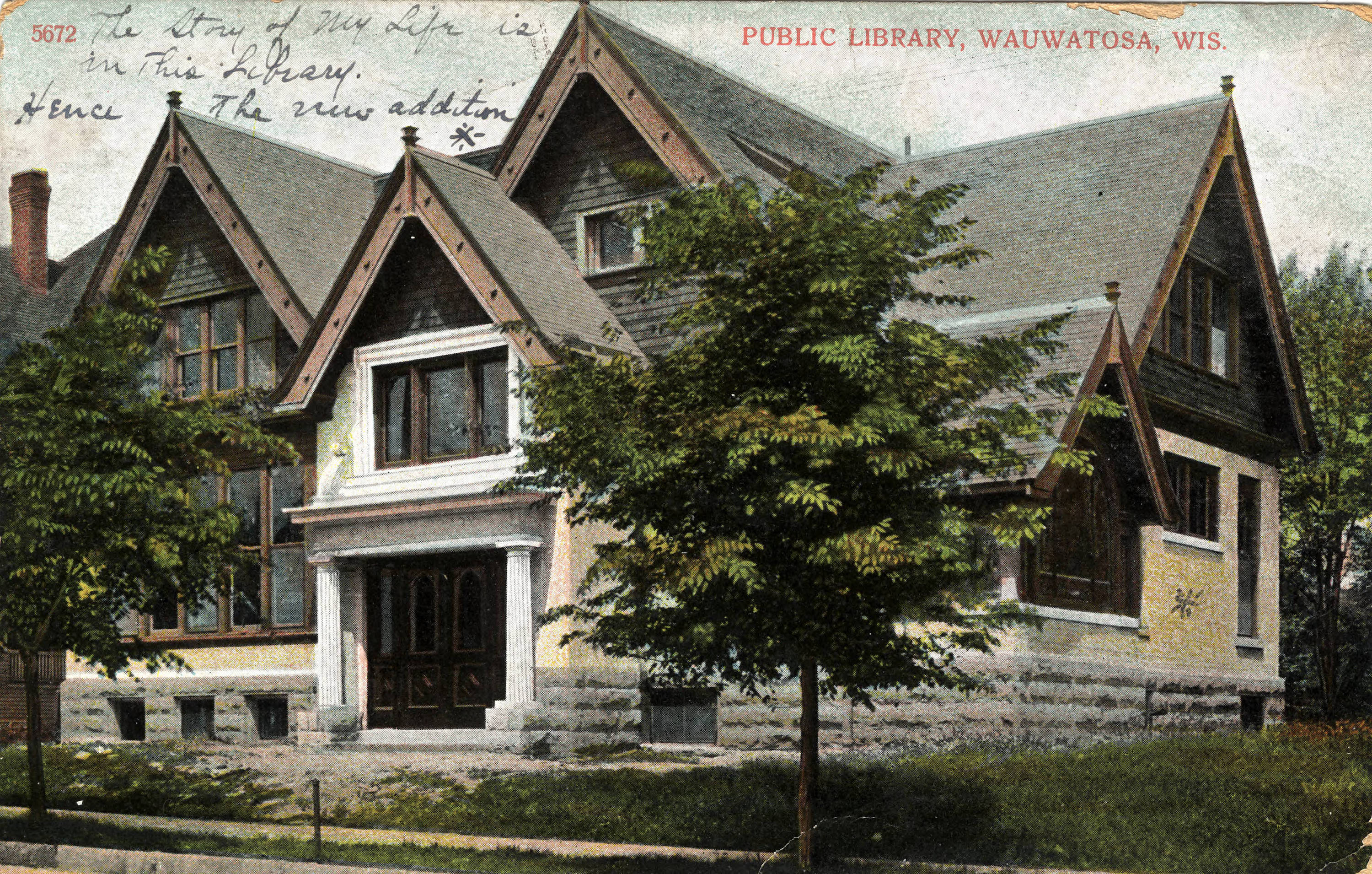

Many of the oldest public libraries in the region began in the latter part of the 19th century as social libraries, which required membership in a social organization and often the payment of dues to use the library.[1] They took several forms, including subscription, circulating, athenaeum, and mechanics’ or mercantile libraries.[2] Social libraries were established in Cedarburg, Oconomowoc, Milwaukee, Waukesha, Wauwatosa, and West Bend. Their collections were later donated to establish free public libraries in those communities. Religious groups and civic organizations, especially women’s civic groups, played a prominent role in the early development of public libraries in Cedarburg, Kewaskum, Menomonee Falls, Port Washington, Waukesha, West Allis, and Whitefish Bay. These groups often organized their own subscription libraries or reading groups, raised funds to purchase books and rent space for storing book collections, promoted the establishment of free public libraries with local city councils, and donated their own collections to start public libraries.[3]

The Wisconsin state legislature passed a public library law in 1872, which enabled cities, towns, and villages to establish free public libraries. The Act allowed communities to collect taxes which could be used to build and support public libraries so that libraries could offer services for free to the general public. Without passage of this act, public libraries could not have been built in the region and supported with taxpayer funds.

Social libraries, civic groups, and the Public Library Act spurred the development of public libraries in the region during the Public Library Movement. Other factors included growing urbanization, civic pride, industrialization (which fueled the need for educated workers), and growing interest in taxpayer support for public institutions, such as libraries.[4] During the Public Library Movement, public libraries were developed in Milwaukee in 1878, and in the 1880s and1890s in Wauwatosa, Mukwonago, Oconomowoc, Hartland, Port Washington, South Milwaukee, Waukesha, West Allis, and West Bend. In the first two decades of the 20th century, public libraries were developed in Shorewood, Hartford, Pewaukee, Delafield, Cudahy (which was originally a branch of the Milwaukee Public Library), Menomonee Falls, Cedarburg, and Kewaskum. The Whitefish Bay Public Library was established somewhat later, in 1937, and Greendale has had public library service since 1938.

In addition to support from civic organizations, South Milwaukee, Waukesha, Wauwatosa, and West Allis received funding in the early 1900s from the Carnegie Corporation of New York to build public libraries in their communities. Inspired by the debt that steel magnate Andrew Carnegie believed he owed to public libraries,[5] the Carnegie funds provided for the actual construction of a library.[6] In return, the communities committed to provide funding to maintain the public libraries.[7]

Several decades passed between early public library development and later public library development in the region. Some communities, including Brookfield, Cudahy, Elm Grove, Hales Corners, and Whitefish Bay were served by the Milwaukee Public Library (MPL) during that time. In exchange for fees paid to MPL by those communities, MPL rented out parts of its collection, offered book mobile services, and allowed patrons from outside of Milwaukee to use its libraries.

As communities in the Milwaukee metropolitan area continued to grow, many wanted their own libraries. As in earlier decades, libraries served as a source of civic pride. In addition, population growth enabled communities to have a sufficient tax base to support their own libraries. Public libraries were established in the 1950s and 1960s in Slinger, Mequon–Thiensville, Grafton, Brookfield, Muskego, Elm Grove, Germantown, Big Bend, Butler, North Lake, Brown Deer, and New Berlin. During the 1970s and 1980s, public libraries were established in Oak Creek, Saukville, Eagle, Hales Corners, North Shore (serving Bayside, Fox Point, Glendale, and River Hills), Franklin, Sussex, Greenfield, and St. Francis. Private benefactors also provided support to build new public library buildings. Those who made significant contributions include Victor L. Braun, Michael F. Cudahy, Herman W. Ladish, and George L.N. Meyer in Cudahy, Frank L. Weyenberg in Mequon-Thiensville, William James Niederkorn in Port Washington, Oscar Grady in Saukville, and Barbara Bartley in Whitefish Bay.

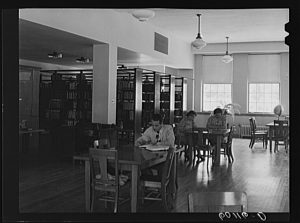

Over the decades, public libraries have responded to the growing demands of the populations that they serve. Most notably, many communities have established special collections, activities, and reading rooms that target children, teens, and young adults. Growing user demands have also placed fiscal constraints on public libraries. To respond to these pressures, all public libraries in the Milwaukee metropolitan region now belong to integrated library systems, which provide coordination of services to reduce operating expenses and give users access to a wider array of materials. Libraries in the region belong to the Eastern Shores Library System, the Mid-Wisconsin Federated Library System, the Milwaukee County Federated Library System, or the Waukesha County Federated Library System.

Just as many public libraries benefitted from civic organizations that promoted their establishment at the turn of the 20th century, many of today’s public libraries have active Friends Associations and/or Library Foundations. Many of these Associations and Foundations have been in existence for nearly as long as the public libraries which they promote. They coordinate fundraisers to support public libraries, encourage local politicians to support public library budgets, volunteer at local libraries, promote library building expansion or redevelopment, and serve as booster groups to promote pride and interest in local public libraries.

While rapidly evolving technology has changed the way many people think about libraries and reading, public libraries in the Milwaukee metropolitan area have adapted and remain strong and relevant cultural institutions.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Michael Harris, ed., Reader in American Library History (Washington, DC: National Cash Register Company, 1971).

- ^ Elizabeth W. Stone, American Library Development, 1600-1899 (New York: Wilson, 1977).

- ^ Elizabeth W. Stone, American Library Development 1600-1899 (New York: Wilson, 1977).

- ^ Arnold K. Bordan, “The Sociological Beginnings of the Library Movement in America,” Library Quarterly (July 1, 1931): 278-82.

- ^ Andrew Carnegie, The Gospel of Wealth and Other Timely Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962), 39.

- ^ Abigail Ayres Van Slyck, Free to All: Carnegie Libraries and American Culture, 1890-1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

- ^ George S. Bobinski, Carnegie Libraries: Their History and Impact on Public Library Development (Chicago: American Library Association, 1969).

For Further Reading

Banda, Ann. Public Library Development in Milwaukee and Montreal. Saarbrücken, Germany: VDM Publishing, 2009.

Augst, Thomas, and Kenneth E. Carpenter, eds. Institutions of Reading: The Social Life of Libraries in the United States. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.