The Oxford Living Dictionaries: English defines “feminism” as the “advocacy of women’s rights on the ground of the equality of the sexes” and dates the English usage of the term to the late nineteenth century.[1] As the “woman movement” achieved its goal of suffrage for women in the early twentieth century, women’s activists began to use the term “feminism” to discuss the advocacy of additional reforms needed to provide women with full economic, social, and political equality.[2] Despite having the vote, women were still routinely kept from and faced discrimination in key areas of American society. Women, for example, were excluded from many jobs, paid less than men for the same job, required to get a husband’s signature when applying for a credit card, and not allowed to join “men only” clubs. By the 1960s, leaders of women’s organizations argued that achievement of suffrage in the early twentieth century was an essential first step but had not produced sufficient change in women’s everyday lives to eradicate their second-class status in American society. They organized a new “feminist movement” to achieve those goals.

This new “women’s rights” or “women’s liberation” movement came to be termed “second-wave feminism.” The new feminist activists added their voices and concerns to the growing swell of civic discontent of the 1960s, alongside racial justice movements, campus movements, anti-war activism, and environmental activism. They pressed for reform on a wide range of issues. In many cases, participants had been part of the other social movements and turned to feminist activism as a way to address women’s issues that the other movements left unaddressed. Feminist activism focused on multiple intersecting fronts: political engagement, access to employment opportunities, and body autonomy, among other causes. Feminists of color sought to address the ways in which race affected their lives differently from white feminists.[3]

Women’s activists took up these feminist goals in the Milwaukee area and were active in national movements as well. Early newsworthy protests highlighted the disabilities and marginalization women faced in local everyday life. Protesters sat in on the Heinemann’s lunch counter “men’s grill.”[4] Journalists challenged the Milwaukee Press Club to admit women and attacked the systemic sexism that did not take their work seriously. They argued that male reporters were assigned to cover “important” stories, while women were relegated to the social and fashion pages despite their qualifications. In other words, women journalists were marginalized in a male-dominated field. Gaining access to the Milwaukee Press Club was a highly public way to challenge their economic marginalization.[5]

Milwaukee women were prominent in the founding of national feminist organization, such as the National Organization for Women (NOW) and the National Women’s Political Caucus. Often they formed local chapters of these organizations. The Milwaukee chapter of NOW dates from 1967 and the National Women’s Political Caucus from 1971. Several local feminist organizations joined to form an “umbrella organization,” the Women’s Coalition, to coordinate feminist initiatives from 1972-1988.[6]

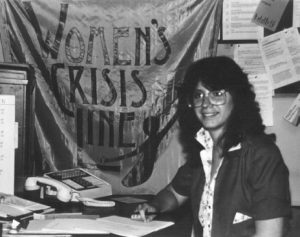

Second-wave feminism focused both on reforming legal barriers to women’s full participation in society and on creating local institutions and “women’s spaces” to organize and press for local reforms.[7] After changes in government funding for social programs under the Reagan and Bush administrations, feminist activism switched primary focus to local campaigns. In Milwaukee, these efforts included anti-rape campaigns and efforts to change how police handled domestic violence situations. Groups such as the Anti-Rape Council and Women Against Rape (WAR) attempted to get the Milwaukee Police Department to adopt a more sensitive approach to questioning rape victims.[8]

Also on the local level, feminists worked to change city zoning so that shelters and day care centers could be created. By accessing state and federal funding, feminist activists were able to institute facilities that would help working class women and women trying to escape domestic violence.[9]

Feminists in Milwaukee also ran for public office and used bureaucratic positions to try to change structural biases against women By 1994, according to political scientist Janet Boles, “there were seven (of 25) female county supervisors, five (of 17) Alderwomen on the Common Council, and four (of nine) female members of the Milwaukee School Board.”[10] Local publishers produced directories of “resources” and “organizations” in the local area. The UWM Center for Women’s Studies produced eleven editions of its “directory” of “Milwaukee Area Women’s Organizations” from 1978 through 2003. The “Women’s Yellow Pages” marked its fourth edition in 1995-96.[11]

By the mid 1990s, “second-wave feminism” had begun to fracture. Observers identified a “third wave” movement, locally and nationally, as the next generation of women’s activists once again pushed the boundaries of gender relationships in culture, politics, and everyday life.[12]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “Feminism,” Oxford Living Dictionaries: English, accessed November 21, 2018.

- ^ Nancy Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989).

- ^ Alice Echols, “Feminist Movement: From 1960 to the Present,” in The Reader’s Companion to American History, Eric Foner and John Garray, eds. (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1991), 394-97; Lori J. Kenschaft, “Feminism,” in A Companion to American Thought, eds. Richard Wightman Fox and James T. Kloppenberg (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, Ltd., 1995), 232-35.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee, Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 379; see also Amy Rabideau Silvers, “Burns Created Heinemann’s Eateries,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 3, 2009, accessed December 9, 2018.

- ^ Kimberly Wilmot Voss and Lance Speere, “Way Past Deadline: The Women’s Fight to Integrate the Milwaukee Press Club,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 92, no.2 (Autumn 2008): 28-43.

- ^ Janet K. Boles, “Local Feminist Networks in the Contemporary American Interest Group System,” Policy Sciences 27, no. 2/3 (1994): 168; J. M. Dombeck, “The Women’s Coalition of Milwaukee, 1972-1987: Feminist Activism at the Local Level.” (MA, University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee, 1987).

- ^ Daphne Spain, Constructive Feminism: Women’s Spaces and Women’s Rights in the American City (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016).

- ^ Boles, “Local Feminist Networks in the Contemporary American Interest Group System.”

- ^ Boles, “Local Feminist Networks in the Contemporary American Interest Group System,” 169.

- ^ Boles, “Local Feminist Networks in the Contemporary American Interest Group System,” 166.

- ^ UWM Center for Women’s Studies, Milwaukee Area Women’s Resource Directory, 11th ed. (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2003); Karen Grishaber, ed., Women’s Yellow Pages of Greater Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Katisch Communications, Inc., 1995).

- ^ Laura Brunell, “The Third Wave of Feminism,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed January 1, 2019.

For Further Reading

Boles, Janet K. “Local Feminist Networks in the Contemporary American Interest Group System.” Policy Sciences 27, no. 2/3 (1994): 161-178.

Dombeck, J. M. “The Women’s Coalition of Milwaukee, 1972-1987: Feminist Activism at the Local Level.” MA, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1987.

Spain, Daphne. Constructive Feminism: Women’s Spaces and Women’s Rights in the American City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016.

Voss, Kimberly Wilmot, and Lance Speere. “Way Past Deadline: The Women’s Fight to Integrate the Milwaukee Press Club.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 92, no.2 (Autumn 2008): 28-43.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.