In 2015, the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society—the publishing arm of the Jehovah’s Witnesses—counted a monthly average of 1,195,081 actively preaching Jehovah’s Witnesses in the United States.[1] While the Society does not keep numbers for individual communities, a 2014 Pew Research Center survey estimated that roughly one percent of adult Wisconsinites self-identified as Witnesses.[2] In the 2010s, Milwaukee-area Witnesses worshipped in twenty-one local congregations at Kingdom Halls in all four Milwaukee-area counties.[3]

The first Jehovah’s Witnesses, at the time known as International Bible Students, arrived in Milwaukee in 1896.[4] Little is known about these early Witnesses or the growth of their movement in Wisconsin. Charles Russell, the leader of the Bible Students and founder of the Watchtower Society, visited Wisconsin as he travelled the country around the turn of the century.[5] The movement (renamed Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1931) expanded rapidly during the Great Depression and World War II.[6] As part of this worldwide expansion, Milwaukee’s first Kingdom Hall, located at 2404 N. 52nd St., opened in 1946.[7]

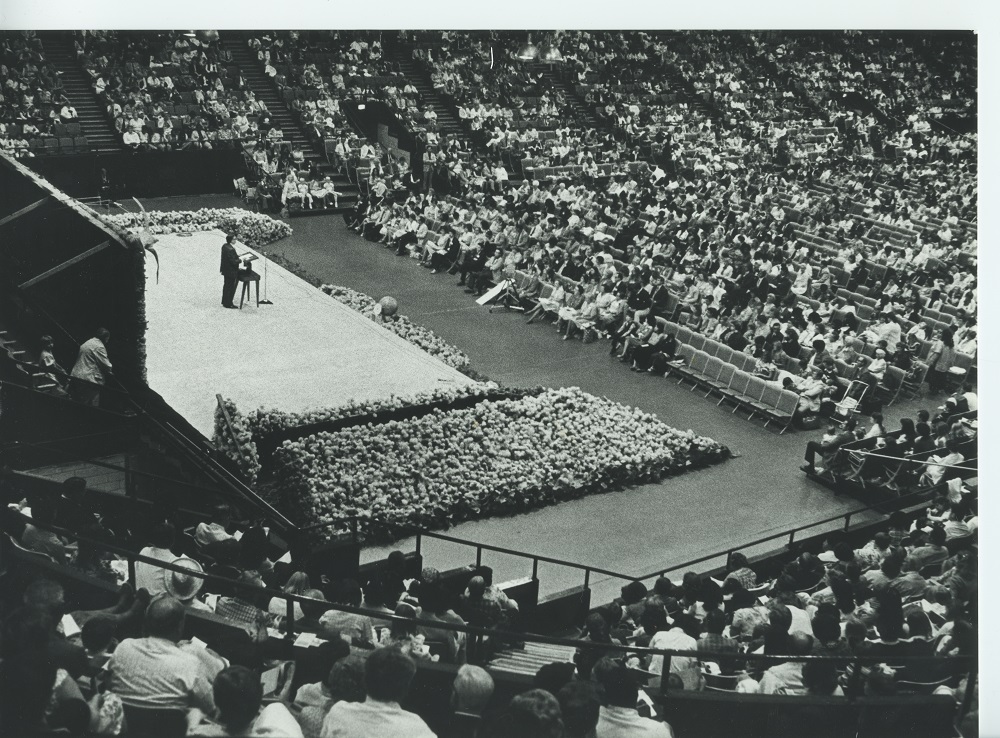

In the following years, Milwaukee welcomed Witness assemblies at the Auditorium, Arena, and County Stadium.[8] At least six large conventions were held at the Stadium from the 1950s through the 1970s.[9] These multiday events often featured mass baptisms at local swimming pools or temporary fonts in the stadium and attracted Witnesses from a variety of states and foreign countries.[10] The 1963 international convention had Sunday attendance of about 57,055—more people than the Stadium held during any of the Braves’ World Series games.[11] Miller Park hosted about 35,000 people at its first Jehovah’s Witness convention in 2014.[12]

Throughout the twentieth century, local Witnesses, like their coreligionists worldwide, faced legal challenges to such tenets of their faith as opposition to blood transfusions, refusal to swear allegiance to earthly institutions, and evangelization in the public sphere.[13] In many local cases, spanning from World War II through the 1960s, Witnesses were imprisoned for failing to report for military service or alternative work.[14] One local immigrant saw his American citizenship rescinded when he refused to swear an oath of service to the United States.[15]

Southeastern Wisconsin native Olin R. Moyle played an important role in the Witnesses’ legal defense when serving as the Watchtower Society’s chief lawyer from 1935 to 1939.[16] Moyle argued before the Supreme Court on behalf of the Witnesses and helped to guarantee the freedom to proselytize.[17] In 1938, he authored the Watchtower Society’s first guide for door-to-door missionaries, explaining the first amendment freedoms that protected their activities.[18]

Troubled by practices he claimed to have observed within Watchtower’s New York headquarters, however, Moyle penned an open resignation letter in 1939.[19] The Watchtower leadership denied these accusations and attacked Moyle in their publications.[20] Moyle sued the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, winning $30,000 (later reduced to $15,000) in damages.[21]

Moyle was excommunicated from both the national and Milwaukee congregations. His split with the Watchtower leadership caused a rift within the Jehovah’s Witness communities of Milwaukee.[22] While most Milwaukee Witnesses remained faithful to the Watchtower Society, Moyle began an independent journal, The Bible Student Inquirer (later The Bible Student Examiner), which ceased publication in the 1980s.[23]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ The Watchtower Society counts as active members only “publishers,” that is, those involved in preaching to others during a given month. 2016 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (Wallkill, NY: Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York, Inc., 2016), accessed October 19, 2016, pdf version, “2015 Service Year Report of Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

- ^ “Adults in Wisconsin,” Pew Research Center Religious Landscape Study, Pew Research Center website, 2014, accessed October 19, 2016.

- ^ Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies, “Metro-Area Membership Report: Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI, Metropolitan Statistical Area,” Association of Religion Data Archives, 2010, accessed October 19, 2016; In 2016, Kingdom Halls were located in Milwaukee, Greenfield, Oak Creek, Mequon, Waukesha, Pewaukee, Germantown, Mukwonago, Grafton, Delafield, Hartford, Oconomowoc, and West Bend. A single building may house multiple congregations. “Find a Meeting of Jehovah’s Witnesses,” Jehovah’s Witnesses website, https://www.jw.org/apps/E_SRCHMTGMAPS, accessed September 29, 2016, now available at https://www.jw.org/en/jehovahs-witnesses/meetings/, last accessed August 24, 2017.

- ^ James M. Johnston, “Witnesses Are Politely Persistent,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 11, 1965.

- ^ Jehovah’s Witnesses in the Divine Purpose (Brooklyn, NY: Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York, Inc., 1959), 50-51.

- ^ M. James Penton, Apocalypse Delayed: The Story of Jehovah’s Witnesses, 2nd ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 62, 68, 84.

- ^ Johnston, “Politely Persistent.”

- ^ For examples at the Auditorium, see “Sect Leader Hits Religions,” Milwaukee Journal, April 14, 1952; Alicia Armstrong, “Jehovah’s Witnesses Shrug Off Hostility, Keep Preaching Their ‘Answer’ to Life,” Milwaukee Journal, November 11, 1961; “Oppression of Witnesses Described,” Milwaukee Journal, December 22, 1975. For examples at the Arena, see Armstrong, “Shrug Off Hostility”; Richard L. Kenyon, “10,000 Witnesses Gather at Arena,” Milwaukee Journal, July 5, 1979; Richard L. Kenyon, “Take a Message: And Jehovah’s Witnesses Do,” Milwaukee Journal, July 7, 1979; Alicia Armstrong, “Foul Weather is Good to Jehovah’s Witnesses,” Milwaukee Journal, November 27, 1965.

- ^ “Jehovah’s Witnesses Open Convention,” Milwaukee Journal, July 17, 1957; Johnston, “Politely Persistent”; “Witnesses Criticize Teen Agers’ Dating,” Milwaukee Journal, July 5, 1968; Fred Holper, “Witnessed Warned of Armageddon,” Milwaukee Journal, July 19, 1971; Linda B. Maiman, “Dedication,” Milwaukee Journal, June 28, 1974; “Witnesses Open Assembly,” Milwaukee Journal, July 21, 1977; Richard L. Kenyon, “10,000 Witnesses Gather at Arena,” Milwaukee Journal, July 5, 1979.

- ^ “Jehovah’s Witnesses Open Convention”; Holper, “Witnessed Warned of Armageddon”; Maiman, “Dedication”; “500 ‘Witnesses’ Use Park Pool for ‘Greatest’ of Days—Baptism,” Milwaukee Journal, July 19, 1957.

- ^ Johnston, “Politely Persistent.”

- ^ Rich Kirchen, “Milwaukee Brewers Diversify Beyond McCartney, Chesney Concerts, Add Jehovah’s Witnesses,” Milwaukee Business Journal, June 19, 2014; Tom Kertscher, “Jehovah’s Witnesses Wrapping Up Event at Miller Park,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 22, 2014.

- ^ For example of blood transfusion case, see “Father Loses Plea to Prevent Transfusion for Newborn Son,” Milwaukee Journal, January 13, 1965. For example of evangelization case, see “End Religious Ban in Parks,” Milwaukee Journal, December 5, 1950.

- ^ For examples of conscientious objector cases, see “Upholds Term for a ‘Conchie,’” Milwaukee Journal, June 6, 1943, and “Son, Like His Father, Gets Draft Law Term,” Milwaukee Journal, June 10, 1966.

- ^ John G. Shaver, “Conscience Proves Costly,” Milwaukee Journal, March 17, 1971.

- ^ Penton, Apocalypse Delayed, 80-81.

- ^ Lovell v. City of Griffin, 303 U.S. 444 (1938).

- ^ Jennifer Jacobs Henderson, “The Jehovah’s Witnesses and Their Plan to Expand First Amendment Freedoms,” Journal of Church and State 46, no. 4 (Autumn 2004): 824.

- ^ Penton, Apocalypse Delayed, 81.

- ^ Penton, Apocalypse Delayed, 81-83.

- ^ Jerry Bergman, comp., Jehovah’s Witnesses: A Comprehensive and Selectively Annotated Bibliography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999), 305.

- ^ “Appendix B: Olin Moyle’s Original Letters,” in Edmond Charles Gruss, Apostles of Denial: An Examination and Exposé of the History, Doctrines and Claims of the Jehovah’s Witnesses (Newhall, CA: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 1970), 291; Penton, Apocalypse Delayed, 83.

- ^ Penton, Apocalypse Delayed, 83; Bergman, Jehovah’s Witnesses, 305-306.

For Further Reading

Bergman, Jerry, comp. Jehovah’s Witnesses: A Comprehensive and Selectively Annotated Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999.

Henderson, Jennifer Jacobs. “The Jehovah’s Witnesses and Their Plan to Expand First Amendment Freedoms.” Journal of Church and State 46, no. 4 (Autumn 2004): 811-832.

Penton, M. James. Apocalypse Delayed: The Story of Jehovah’s Witnesses. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.