Milwaukee’s German-language press, much like the city’s German community in general, was characterized by its size and diversity. Half of Milwaukeeans claimed German ancestry in 1910, and the German language was omnipresent in the “German Athens” (Deutsch-Athen) during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many immigrants turned to the German-language press as a bridge between the old world and the new country. German papers informed their readers about political developments on both sides of the Atlantic, reprinting stories published in German and American papers. The papers increasingly covered local news that was of importance to the German-American community, such as notices of meetings and events held by one of the German associations or churches.[1] However, beyond a defense of alcohol consumption, Sunday entertainment, and immigrant voting rights, there was little that German newspapers had in common. German immigrants could choose from numerous papers representing different religious and political groups.

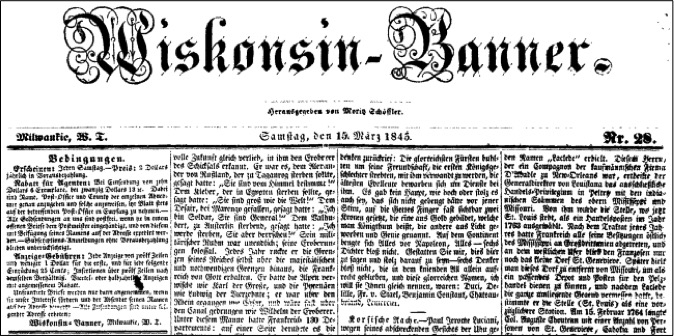

Most German-language papers in Milwaukee’s early days were established as political organs promoting the Democratic and Republican parties.[2] The city’s pioneer German-language newspaper, the Wiskonsin Banner, was first published in 1844 and affiliated with the Democrats. Editor-politician Moritz Schöffler founded the paper with the financial help of Franz Hübschmann and became an influential figure in the German community himself within short time.[3] The paper presented the German immigrants’ point of view on political matters, advocating for their rights in their native tongue and was thus welcomed by the German community. Franz Hübschmann, for example, kept his readers informed while representing the Germans at the first Constitutional Convention in Madison, and the Banner published a German translation of the first Constitution of Wisconsin in early 1847.[4] By 1850, the Wisconsin Banner had altered the spelling of its title and counted 4,000 weekly and 1,400 daily subscribers, making it the second-largest Milwaukee newspaper after the English-language Sentinel.[5]

In early 1847, Sentinel editor Rufus King established the second German-language newspaper, Der Volksfreund, as a Whig counterweight to the popular Banner. The paper was later bought by Democrat Friedrich Fratney, who changed its politics. Despite the papers’ similarities and general support of the Democratic Party, the Wisconsin Banner and the Volksfreund editors were adversaries at first, frequently attacking each other in their papers. Shortly before his death, however, Fratney transferred his paper to Schöffler.[6] In 1855, the formerly competing papers were merged to form the Banner und Volksfreund, which continuing to publish daily editions until 1880 and weekly editions until 1913.[7] The paper was highly popular in the largely Democratic German community in Milwaukee.

The Republican papers of the time were failures in comparison: Bernhard Domschcke’s Korsar (1854-1856) and Milwaukee Journal (1856) were short-lived. Domschcke, who fled his native Germany after the failed Revolutions of 1848, then founded the more successful Atlas in 1856, a paper supported by German revolutionary and Republican activist Carl Schurz. Other prominent Milwaukeeans, including German socialist Fritz Anneke, served as editors.[8] The Atlas was discontinued in 1861.[9]

The Catholic Seebote emerged in 1851. The Seebote’s readers were mainly Roman Catholic Germans who opposed the anticlerical views of the Banner and Volksfreund papers.[10] Beginning in 1856, the Seebote was edited by Peter V. Deuster, a Democrat and later Congressman, and it quickly became one of Wisconsin’s leading German-language papers.[11] A paper written by and for German women was founded by social activist and suffragette Mathilde Franziska Anneke. Die Deutsche Frauen-Zeitung was the first feminist newspaper published by a woman in the United States, and it was printed in Milwaukee in 1852.[12]

At the peak of German-language publishing in Milwaukee in the late nineteenth century, the market was dominated by the Herold Company (Coleman family) and George Brumder’s giant Germania Publishing Company. Bernhard Domschcke had collaborated with W. W. Coleman to found the Republican Herold in 1861. The Milwaukee Germania first appeared in 1873. It was essentially a Democratic paper, but the editors claimed to be politically independent. The history of German papers in Milwaukee is also a story of mergers: as the demand for German papers began declining toward the turn of the century, the Seebote was absorbed by the Herold in 1898. The Herold and Germania companies merged and became the Herold-Germania Association in 1906 but continued to publish separate papers. The last edition of the Germania was printed in 1924 while the Milwaukee-Herold continued publication until 1982.[13]

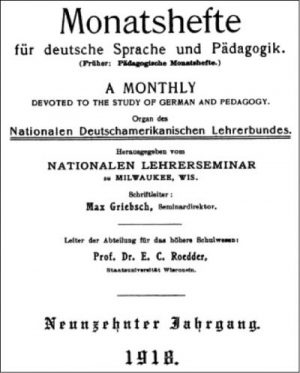

Milwaukee’s long history of Socialist politics had a major impact on the German-language press too. The Freidenker (1872-1942) and Victor Berger’s Wisconsin Vorwärts (1892-1932) were well-read “freethinker” and socialist papers. German influence on education in Wisconsin, where Margarethe Schurz founded the first kindergarten in the U.S. and where Peter Engelmann directed the German-English Academy (also known as “Engelmann School”) led to the publication of specialist journals.[14] Titles included the Amerikanische Schulzeitung (1870-1899), the Lehrer Post (1884-1891) or the Monatshefte für deutsche Sprache und Pädagogik (1906-1927), a monthly magazine devoted to training teachers of German in Milwaukee and nationwide.[15]

In the 20th century, farm and family magazines became more popular than newspapers. A prime example was the women’s journal Die Deutsche Hausfrau, first printed by the Herold Company in Milwaukee in 1904. The Hausfrau sold 132,000 subscriptions in 1907 and still between 40,000 and 50,000 after World War I. It featured tips on housekeeping as well as German short stories and became a regular companion in many German-American households. The journal was published in Milwaukee for nearly fifty years.[16]

The decline of German papers in the early 20th century coincided with decreasing immigration from Germany and anti-German sentiment following World War I. In addition, second-generation immigrants had become “Americanized” and preferred English-language papers over German ones.[17] By the 1930s, there were only few of the Milwaukee newspapers left, and most German-language publications were technical journals and periodicals.[18] The remaining newspapers focused on promoting German culture in the city: events organized by one of the German associations and German films shown in Milwaukee’s theaters were announced in publications like the Abendpost und Milwaukee Deutsche Zeitung (1950-1991). German radio programs included German, Swiss, and Austrian radio shows on Milwaukee’s radio channels.[19] One of the most popular German radio shows was started in 1955 by Herbert Wittka and still exists today: Continental Showcase, the longest-running German radio show in Milwaukee.[20]

Today, the considerably smaller German community in Milwaukee makes use of new forms of communication. German-American associations reach out to members via social media and blogs, and Germans in Milwaukee have access to a wide array of German-language media online.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), 184-189.

- ^ Carolyn Stewart Dyer, “Political Patronage of the German-American Press in Antebellum Wisconsin,” in The German-American Press, ed. Henry Geitz (Madison, WI: Max Kade Institute for German-American Studies, 1992), 227.

- ^ Anke Ortlepp, Auf denn, ihr Schwestern! Deutschamerikanische Frauenvereine in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1844-1914 (Stuttgart: F. Steiner, 2004), 40.

- ^ Carl Heinz Knoche, “The German Immigrant Press in Milwaukee” (Ph.D. diss., The Ohio State University, 1969), 19-24.

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 184-189.

- ^ Thomas Logge, Zur medialen Konstruktion des Nationalen: Die Schillerfeiern 1859 in Europa und Nordamerika (Göttingen: V&R unipress, 2014), 364-366.

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 184-189.

- ^ Bernhard Domschcke. “Die tägliche Ausgabe des Atlas,” Atlas, November 29, 1858.

- ^ Knoche, “The German Immigrant Press in Milwaukee,” 69.

- ^ Alison Clark Efford, “The Appeal of Racial Neutrality in the Civil War-Era North: German Americans and the Democratic New Departure,” Journal of the Civil War Era 5 (2015): 68-96.

- ^ Logge, Zur medialen Konstruktion des Nationalen: Die Schillerfeiern 1859 in Europa und Nordamerika, 364-366.

- ^ Maria Wagner, Mathilde Franziska Anneke in Selbstzeugnissen und Dokumenten (Frankfurt a. M.: Fischer, 1980), 67; Rudolph A. Koss, Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Herold, 1971), 382-383.

- ^ Karl J. R. Arndt and May E. Olson, German-American Newspapers and Periodicals, 1732-1955: History and Bibliography (Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer, 1961), 668-98; Linda Steiner. “An Era Ends: Milwaukee’s Last German-Language Newspaper Closes,” Milwaukee Journal, June 9, 1982.

- ^ National German-American Teachers’ Seminary Alumni Association, The Engelmann Heritage (Milwaukee: National Teachers’ Seminary Alumni Association, 1951).

- ^ Arndt and Olson, German-American Newspapers and Periodicals, 668-98; National German-American Teachers’ Seminary Alumni Association, The Engelmann Heritage.

- ^ Monika Blaschke. “Communicating the Old and the New: German Immigrant Women and Their Press in Comparative Perspective around 1900,” in People in Transit: German Migrations in Comparative Perspective, 1820-1930, eds. Dirk Hoerder and Jörg Nagler (Washington D.C.: University of Cambridge Press, 1995), 318-319.

- ^ Wilhelm Hense-Jensen and Ernest Bruncken, Wisconsin’s Deutsch-Amerikaner bis zum Schluß des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, vol. 2. (Milwaukee: Verlag der Deutschen Gesellschaft, 1902), 256-257.

- ^ Joseph Salmons, “The Shift from German to English, World War I and the German-Language Press in Wisconsin,” in Menschen zwischen zwei Welten. Auswanderung, Ansiedlung, Akkulturation, eds. Walter G. Rödel and Helmut Schmahl (Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2002), 179-193.

- ^ “Deutsche Radiostunden in Milwaukee, Lichtspielhäuser –Kino,” Abendpost und Milwaukee Deutsche Zeitung, July 3, 1950.

- ^ “Milwaukee’s Best German Radio Show,” Continentalshowcase website, last accessed August 2, 2016.

For Further Reading

Arndt, Karl John Richard, and May E. Olson, German-American Newspapers and Periodicals, 1732-1955: History and Bibliography. Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer, 1961.

Conzen, Kathleen Neils. Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976.

Knoche, Carl Heinz. “The German Immigrant Press in Milwaukee.” Ph.D. diss., The Ohio State University, 1969.

Salmons, Joseph. “The Shift from German to English, World War I and the German-Language Press in Wisconsin.” In (ed.). Menschen zwischen zwei Welten. Auswanderung, Ansiedlung, Akkulturation, edited by Walter G. Rödel and Helmut Schmahl, 179-193. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2002.

Stewart Dyer, Carolyn. “Political Patronage of the German-American Press in Antebellum Wisconsin: A Case Study in Political Assimilation.” In The German-American Press, edited by Henry Geitz, 227-241. Madison, WI: Max Kade Institute for German-American Studies, 1992.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.