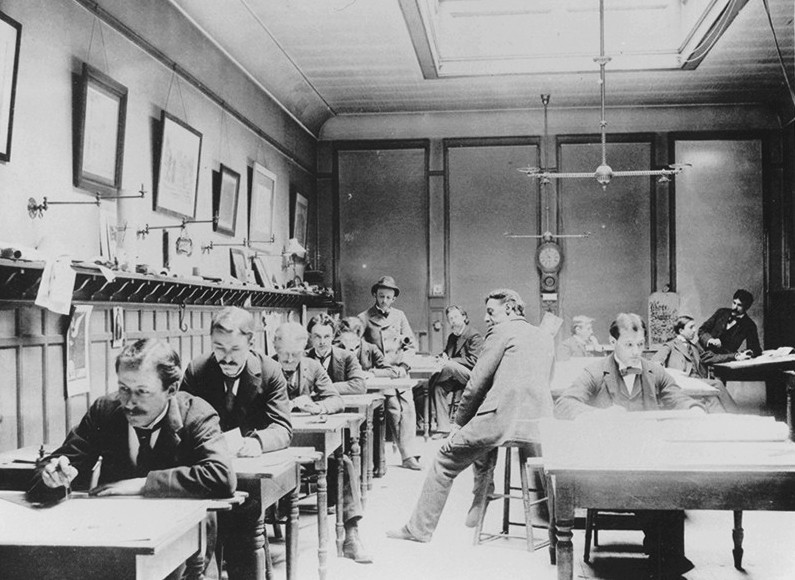

Milwaukee’s built environment reflects the ideas of the architects and builders who designed and constructed the area’s commercial, industrial, and residential buildings. The roots of the profession began in the city’s first decade and flourished in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. A proliferation of architectural firms in the twentieth century accounts for Milwaukee’s varied and distinctive skyline.

The four most well-known and prolific early architect/builders in Milwaukee were John F. Rague, Victor Schulte, James Douglas, and George W. Mygatt.[1] They began designing buildings in the mid to late 1840s, during the first wave of European immigration and land speculation. Their designs were mostly simple brick and wooden structures in the federal, Greek Revival, and Italianate styles. Rague worked in Milwaukee on commissions like the Layton House on Forest Home Avenue before he relocated to Dubuque, Iowa in 1854. Victor Schulte’s 1847 design of St. John’s Cathedral was one of the more elaborate brick buildings of the mid-nineteenth century. He was one of the foremost architects of churches in the city before he retired in 1868. James Douglas developed designs referred to as the “Douglas-style” for his elaborate High Victorian residences.[2] In the early 1880s he drew plans for the New Hampshire Block, the first apartment building in the city. George W. Mygatt designed many still existing commercial buildings and residences, such as the Diedrichs house on Franklin Street and the Benjamin Miller home on Marshall Street in Milwaukee. Mygatt worked nearly until his death in 1883. His influence continued in the work of his “most successful” apprentice, Henry C. Koch, and also his former draftsman, Herman Schnetzky.

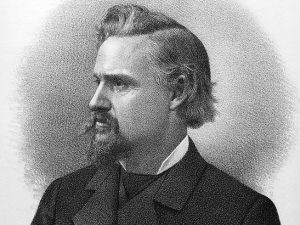

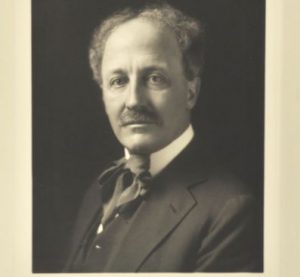

By 1857, when the American Institute of Architects was established, architecture had become a dedicated profession in the United States.[3] The latter half of the nineteenth century was a time of great growth, leading to a need for highly trained architects to design the period’s more complex buildings. The two Milwaukee architects who led the profession in the late nineteenth century were Edward Townsend Mix, whose influence appears as early as 1856,[4] and Henry C. Koch, who began his own firm in 1870.[5] Architectural partnerships which also developed during this period also included H. Messmer & Co. in 1873, Crane & Barkhausen in 1888, Ferry & Clas in 1890, and Schnetzky & Liebert (who started as Schnetzky’s draftsman in 1887). Notable projects from these architects included the neoclassical Milwaukee Central Library by Ferry & Clas, the Flemish Renaissance Milwaukee City Hall by Henry C. Koch, the Classical Revival Germania building by Schnetzky & Liebert, the Romanesque Revival Button Block by Crane & Barkhausen, and the Gothic Revival National Soldiers Home by Edward Townsend Mix.

The nineteenth century firms trained the next generation of architects, who continued developing the built environment of the city into the early twentieth century. Ferry & Clas trained Alexander Eschweiler, Richard Philipp, Peter Brust, Elmer Grey, Julius Heimerl, and William Schuchardt. Henry Messmer trained Charles Kirchhoff.[6] Henry Koch trained Gustave Dick, Herman Esser, Henry Hensel, and his son Armand Koch. E.T. Mix trained W.A. Holbrook and Henry Van Ryn. This new batch of architects further developed the quality of work in the city, using new materials and styles. The Christian Science Church designed by Elmer Grey introduced a new style to the city that contrasted with the Richardsonian Romanesque churches of the nineteenth century. The Public Service Building by Herman Esser is a neoclassical design that was much more modern than previous train stations. Charles Kirchoff formed a partnership with Thomas Rose to construct buildings such as the Empire Building and the Neo-classical Second Ward Savings Bank. Alexander Eschweiler built many of the most iconic and enduring buildings, including the art deco style Milwaukee Gas Light Building and the Bell Telephone Building.

The nationally strong economy of the 1920s drove growth and development throughout the city. Before the stock market crash of 1929 stopped new building construction, a new crop of architects used modern technologies to make their mark on the face of the city. The most successful of these newer firms were Martin Tullgren & Sons, Van Ryn & de Gelleke, Russell Barr Williamson, and Fitzhugh Scott, each with their signature styles. Martin Tullgren started as a Chicago architect and relocated his business to Milwaukee in 1902. When Martin died in 1922, his son Herbert W. took over the firm and designed the unique Viking apartments and hotels like the Shorecrest. The partnership of Van Ryn & de Gelleke began in 1897, but between 1912 and 1925 they designed most of the school buildings in the city including the Milwaukee Vocational School (now Milwaukee Area Technical College). Russell Barr Williamson was associated with Frank Lloyd Wright until 1918.[7] He was well known for several large hotels downtown in the late 1920s, including the Antlers and Randolph hotels, and also his version of prairie style homes. Fitzhugh Scott began his career working in the office of Alexander Eschweiler but started his own practice with his brother in 1914.[8] The most important building Scott designed was the Allen-Bradley building.

Fitzhugh Scott Jr. continued the firm in his father’s footsteps, training architects David Kahler and Thomas Slater. They eventually continued the company under its current name of Kahler Slater.[9] It is the oldest architectural office in the city. This firm is responsible for many high profile projects in the city and throughout the United States. Some of their local projects include the Milwaukee Marriott Downtown and the Bradley Center.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Alexander Carl Guth, “Early Day Architects in Milwaukee,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 10, no. 1 (September 1926): 17-28.

- ^ Built in Milwaukee: An Architectural View of the City: Prepared for the City of Milwaukee, Wisconsin by Landscape Research ([Milwaukee]: City of Milwaukee, Dept. of City Development, 1983), 139.

- ^ Richard W. E. Perrin, Milwaukee Landmarks ([Milwaukee]: Milwaukee Public Museum 1979), 7.

- ^ Mary Ellen Pagel, “Edward Townsend Mix,” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society (December 1965): 110-116

- ^ “Henry C. Koch,” The Western Builder IX, no. 1 (June 1910).

- ^ Anna Marie Passante, A God-Given Talent: Peter J. Brust, Architect: His Work and Legacy, 1906-2006. Milwaukee, WI: ElexDay Publications, 2006.

- ^ Built in Milwaukee: An Architectural View of the City: Prepared for the City of Milwaukee, Wisconsin by Landscape Research. [Milwaukee]: City of Milwaukee, Dept. of City Development, 1983.

- ^ City of Milwaukee, “Historic Preservation Study Report, Myron T. MacLaren House,” (Spring 1991).

- ^ “Fitzhugh Scott, Associates Realign Architectural Firm,” The Milwaukee Journal, December 10, 1974.

For Further Reading

“Architects of the City.” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 27, 1892.

Bate, Arthur, “Growth of Art—Builders and Architects Deserve Credit.” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 19, 1890.

Built in Milwaukee: An Architectural View of the City: Prepared for the City of Milwaukee, Wisconsin by Landscape Research. [Milwaukee]: City of Milwaukee, Dept. of City Development, 1983.

Guth, Alexander Carl. “Early Day Architects in Milwaukee.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 10, no. 1 (September 1926): 17-28.

“James Douglas is Dead—Pioneer Architect of the City Passes Away.” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 1, 1894.

Pagel, Mary Ellen. “Edward Townsend Mix.” Historical Messenger (December 1965).

Passante, Anna Marie. A God-Given Talent: Peter J. Brust, Architect: His Work and Legacy, 1906-2006. Milwaukee, WI: ElexDay Publications, 2006.

Perrin, Richard W. E. Milwaukee Landmarks. [Milwaukee]: Milwaukee Public Museum, 1979.

“The Building Trades—Architects.” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 1, 1895.

Van Valkenburgh, Helen. “Evolution of Milwaukee Architecture.” Milwaukee Free Press, November 12, 1911.

Zimmermann, H. Russell. 1976. The Heritage Guidebook: Landmarks and Historical Sites in Southeastern Wisconsin: Historically and/or Architecturally Significant Buildings, Monuments, and Sites in Five Southeastern Wisconsin Counties. Milwaukee: Heritage Banks, Inland Heritage Corp.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.