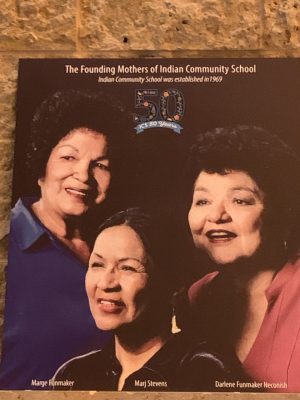

In 1969, three Oneida women—Marj Stevens, Marge Funmaker, and Darlene Funmaker Neconish—took it upon themselves to offer an alternative education for their own children and other disillusioned Native youth in Milwaukee.[1] Born of their frustrations with the public school system, discrimination against Native students, and a lack of cultural direction, these Oneida women began teaching Indigenous children in Stevens’s living room apartment and taught a curriculum that privileged Native histories, cultures, and communities. What started as seven students quickly grew into thirty-six, so the homeschooling operation moved to larger quarters in the basement of the Church of All People (21st & Highland St.).[2]

In August 1971, the local chapter of the American Indian Movement (AIM) occupied an abandoned Coast Guard station along the Milwaukee lakefront in an effort to raise awareness about Native American issues while also claiming that property by rights of the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868). After negotiations with AIM members, both the city and Bureau of Indian Affairs agreed to hand control of that facility over to the organization on the grounds that the building would be used as a cultural, educational, and community center. By September, Stevens, Funmaker, and Neconish relocated their school to the station and provided instructional services to more than sixty-nine students. That same year, the school was incorporated as a nonprofit institution known as the Indian Community School of Milwaukee.[3]

Inspired by AIM’s “survival schools” in Minneapolis, the Indian Community School revolved around a historically and culturally-relevant curriculum for Native youth.[4] In addition, the school encouraged collaboration with the local indigenous community, attracted teachers and volunteers from Wisconsin reservations and Native students at UWM, and flourished under the leadership of Dorothy LePage (Menominee), who held a nursing degree, a Bachelor’s in elementary education, and a Master’s in social work. As LePage put it, parents sent “their children [here]…to learn about their Indian heritage.”[5] By 1978, Milwaukee County was interested in turning the Coast Guard Station into a tourist attraction or restaurant. Likewise, the school struggled to maintain the aged station while educating students. Eventually the school agreed to move into the derelict Bartlett Avenue School (2964 N. Bartlett Avenue) in 1980. Because funding was cut during the Reagan administration, the school closed its doors in 1983.[6]

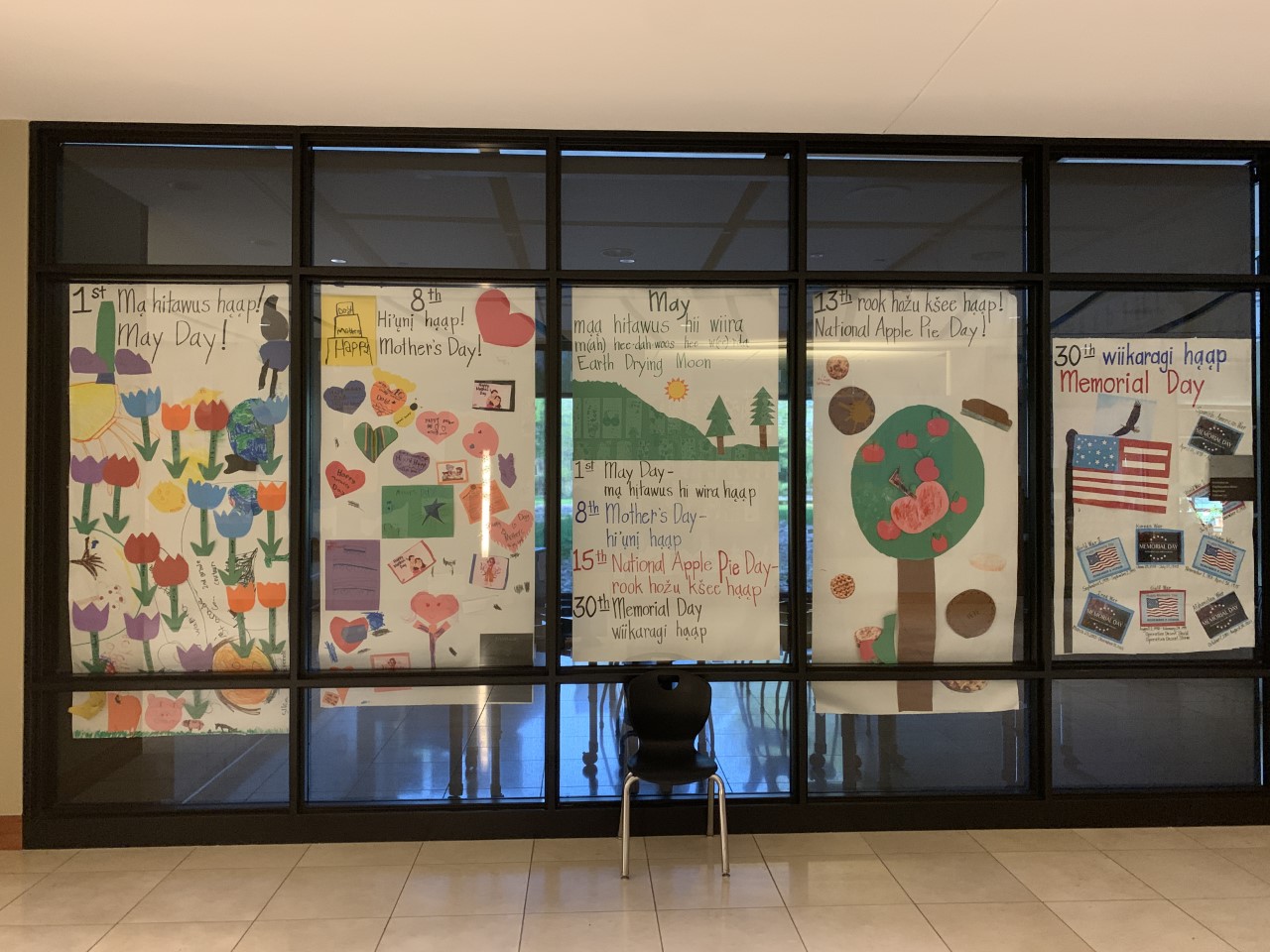

Yet this did not deter indigenous leadership, led by women like Loretta Ford (Ojibwe), Phil Bautista (Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan), and others, who found the means to sell the Bartlett Avenue location and then purchase the former site of Concordia College (3134 W. State Street), where the Indian Community School reopened in January 1987.[7] To create a sustainable funding source for the school, the ICS board petitioned for trust land status, negotiating with city, county, state, and federal governments. ICS pitched the idea of trust land status to all of Wisconsin’s tribes, and it was the Forest County Potawatomi who stepped in as a partner, along with Omni Bingo, which established a high-stakes bingo operation. Forest County Potawatomi agreed to a twenty-year lease that was finalized in 1990. The tribe also agreed to a gaming-revenue sharing agreement that would fund the school’s operations, in exchange for land in the Menomonee River Valley where Potawatomi Hotel & Casino is located today.[8] In 1999, the ICS board purchased land in Franklin, where construction on a new school building began in 2005. The new ICS opened its doors for the 2007 school year at 10405 W. St. Martins Road, where it provides tuition-free education to students from over fifty different tribal Nations. ICS also offers instruction in four Native languages, and through its Our Ways, Teaching, and Learning Framework™, seeks to cultivate in students “an enduring cultural identity and critical thinking by weaving indigenous teachings with a distinguished learning environment.”[9]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Indian Community School Weekly Report, vol. 41, issue 23 (February 20, 2014): 1; Yvonne Kaquatosh, “‘We Are Home’: Ceremony Held at New Milwaukee Indian Community School,” Kalihwisaks: Official Newspaper of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin (Oneida, WI), September 13, 2007, p. 5A. This entry was first posted on June 4, 2018 and updated on November 30, 2021.

- ^ Susan Applegate Krouse, “What Came out of the Takeovers: Women’s Activism and the Indian Community School of Milwaukee,” in Keeping the Campfires Going: Native Women’s Activism in Urban Communities, eds. Susan Applegate Krouse and Heather A. Howard (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 148.

- ^ Krouse, “What Came out of the Takeovers,” 148-149.

- ^ Nicolas G. Rosenthal, Reimagining Indian Country: Native American Migration & Identity in Twentieth-Century Los Angeles (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 146. For specifics about AIM “survival schools,” see Julie L. Davis, Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

- ^ Karen Rothe, “Community News: School Teaches Past, Present of Indian Life,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 21, 1981, p. 6.

- ^ Krouse, “What Came out of the Takeovers,” 151-152.

- ^ Krouse, “What Came out of the Takeovers,”, 153.

- ^ Krouse, “What Came out of the Takeovers,”, 154-155.

- ^ “Our Mission,” Indian Community School of Milwaukee, last accessed November 30, 2021.

For Further Reading

Davis, Julie L. Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Krouse, Susan Applegate. “What Came out of the Takeovers: Women’s Activism and the Indian Community School of Milwaukee.” In Keeping the Campfires Going: Native Women’s Activism in Urban Communities, edited by Susan Applegate Krouse and Heather A. Howard, 146-162. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

My name is Phil Bautista. I was the Vice-Chairman of the Indian Community School of Milwaukee Inc. since 1983 to 1989. I would like to say that what Antonio Doxtator and Renee Zakhar state in the history of the school since 1983 is totally not factual as Loretta Ford who I had known since childhood brought me on to the board to help them re-open the school as they were totally in arrears and did not know what to do. In fact Loretta asked me at the first board meeting if I would be the chairman. I declined and said I would be vice-chairman and take the ball and run with it until the school re-opened. As I made all the contacts for funding none of them were present. I see what Antonio and Renee state is very vague with no mention of facts. All I see is people taking credit and giving credit to people who were not even there. The years of work I did and not even a mention. My name is on all the legal documents for what happened and not theirs. If you want the true story and not one that is fabricated contact me by email at philbautistasr@yahoo.com

Shekoli Phil,

Good to see your still around. With all due respect this article was not written by Antonio or Renee and I was not contacted in regards to it. The information the author used may or may not have come from my book “American Indians in Milwaukee,” the author just lists it among two others for further reading.

I know we personally contacted you several times for photos and information for our book, but never received any. Unfortunately there are many people who did not get mentioned in the book, who should have been-but we could only use what photos and information we could verify from articles and newspapers. Our book does have vague info on a lot of things since we were limited to 50 words per photo. But we tried our best to produce a history our community could be proud of- on our own time and money. I hope others get a chance and are willing to do the same.

If you would like to talk more about the issue please contact me.

Yaw^

Antonio J. Doxtator