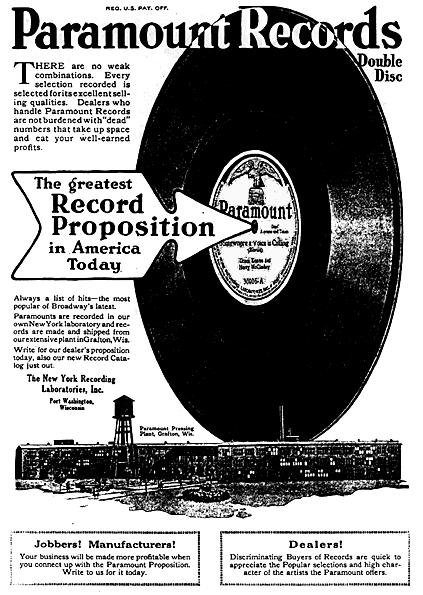

This local recording label strongly impacted the history of early blues music in the 1920s.[1] It was formed in 1917 by the New York Recording Laboratories—a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company located in Grafton.[2] The label’s first recording, “Wedding of the Winds,” was released on June 29, 1917 and was followed by recordings for ethnic audiences, including Germans, Scandinavians, and Mexicans.[3] After struggling to break into the market for popular music, the inexperienced executives at Paramount targeted the untapped African American audience by producing blues music, then known as “race records.”[4] In its brief lifetime, Paramount was responsible for producing approximately one-fourth of all blues recordings released.[5] Recordings took place in New York and Chicago until 1929, and records were pressed at the Grafton furniture factory.[6] New competitors, mismanagement, and the impact of the Great Depression on Paramount’s target audience led executives to scale back from 1929 until the company closed in 1932.[7] Paramount’s biggest stars included Ma Rainey, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Jelly Roll Morton, and Papa Charlie Jackson.[8]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Sarah Filzen, “The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, 82, no. 2 (Winter 1998-99): 104-127.

- ^ Filzen, “The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records,” 109. The Chair Company, which had branched out to make phonographs, sought to produce its own records as a promotional tool to increase phonograph sales. New York Recording Studio Laboratories would operate other labels, but Paramount served as the premier one.

- ^ Don Behm, “The Current Plan—DNR to Demolish Chair Factory Dam in September,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 30, 2000.

- ^ Filzen, “The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records,” 110-111. Companies like Victor and Columbia dominated the popular music market. Paramount gained a reputation as a “race label” in 1923 when it hired its first and only black executive, J. Mayo Williams, who served them from Chicago as a music scout and supervisor of recording sessions. Williams tapped into the growing number of southern blacks migrating north at this time and gained a reputation among black performers for making stars. Artists discovered by southern record store operators and other scouts were often brought to Chicago to work with Williams. In 1924 the label also bought a fledgling New York recording company, Black Swan, which already served an African American clientele.

- ^ Filzen, “The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records,” 124. This figure is estimated for the years between 1922 (when it started producing “race records”) and the company’s demise in 1932-33.

- ^ Dave Tianen, “For a Few Hot Years, Grafton Had the Blues,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 21, 1994.

- ^ Tianen, “For a Few Hot Years, Grafton Had the Blues.” For this brief time, recordings were made in a makeshift studio constructed in the Grafton factory. This remote location also had a negative impact on the business’s growth.

- ^ Filzen, “The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records,” 111-112.

For Further Reading

Calt, Stephen. “The Anatomy of a Race Label—Part One.” 78 Quarterly 3 (1988): 9-23.

Calt, Stephen. “The Anatomy of a Race Label—Part Two.” 78 Quarterly 4 (1989): 9-30.

Kennedy, Rick, and Randy McNutt. Little Labels—Big Sound: Small Record Companies and the Rise of American Music. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Luhrssen, David. “Blues in Wisconsin: The Paramount Records Story.” Wisconsin Academy Review 45 (Winter 1998-99): 17-21.

Rust, Brian. American Record Label Book. New York: Da Capo Press, 1984.

Tuuk, Alex van der. Paramount’s Rise and Fall: A History of the Wisconsin Chair Company and Its Recording Activities. Denver, CO: Mainspring Press, 2003.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.