Milwaukee is Indigenous land. The word Milwaukee comes from the Anishinaabemowin word minowakiing, meaning “good earth.”[1] Anishinaabemowin is the language of the Anishinaabeg or Three Fires Confederacy made up of the Ojibwe, Ottawa, and Potawatomi whose villages dotted Lake Michigan’s coast and whose presence is still felt throughout Wisconsin today. The word referred to a trading and meeting place at the point where the waters of three rivers—the Milwaukee, Menomonee, and Kinnickinnic—meet and flow into Lake Michigan. High bluffs that lined the northern coast gave way to a marshy region abundant in food sources, including wild rice, animals, and birds. This swampy area later plagued American boosters, who ultimately filled in the waters with refuse and dirt, but for the earliest of inhabitants in Milwaukee these marshes were a gift.[2]

People made their homes in the Milwaukee region for thousands of years. Oral tradition and western archeological evidence note ancestors of the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) lived and built earthen mounds in Milwaukee.[3] When the first Frenchman reached the Milwaukee area in the 1600s, they found it was already home to several Native American tribes in addition to the Ho-Chunk. Algonquian speaking tribes including the Meskwaki (Fox), Sauk (Sac), Menominee, Ojibwe (Chippewa), Odawa (Ottawa), and Potawatomi moved into the region during the 1600s.

In the 1640s the Beaver Wars in the eastern Great Lakes precipitated an influx of tribes loosely affiliated through their shared Algonquian language.[4] Encouraged by the growing demand for beaver furs, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) attacked the Wyandot (Huron) and their Potawatomi and Ottawa allies in order to secure a greater supply of furs.[5] While the Haudenosaunee competition contributed to a massive migration west, Algonquian speaking tribes were also pulled west by trade networks, the availability of resources, and spiritual factors. There they found refuge and support with allies at Sault Ste. Marie, Green Bay, and Milwaukee.[6]

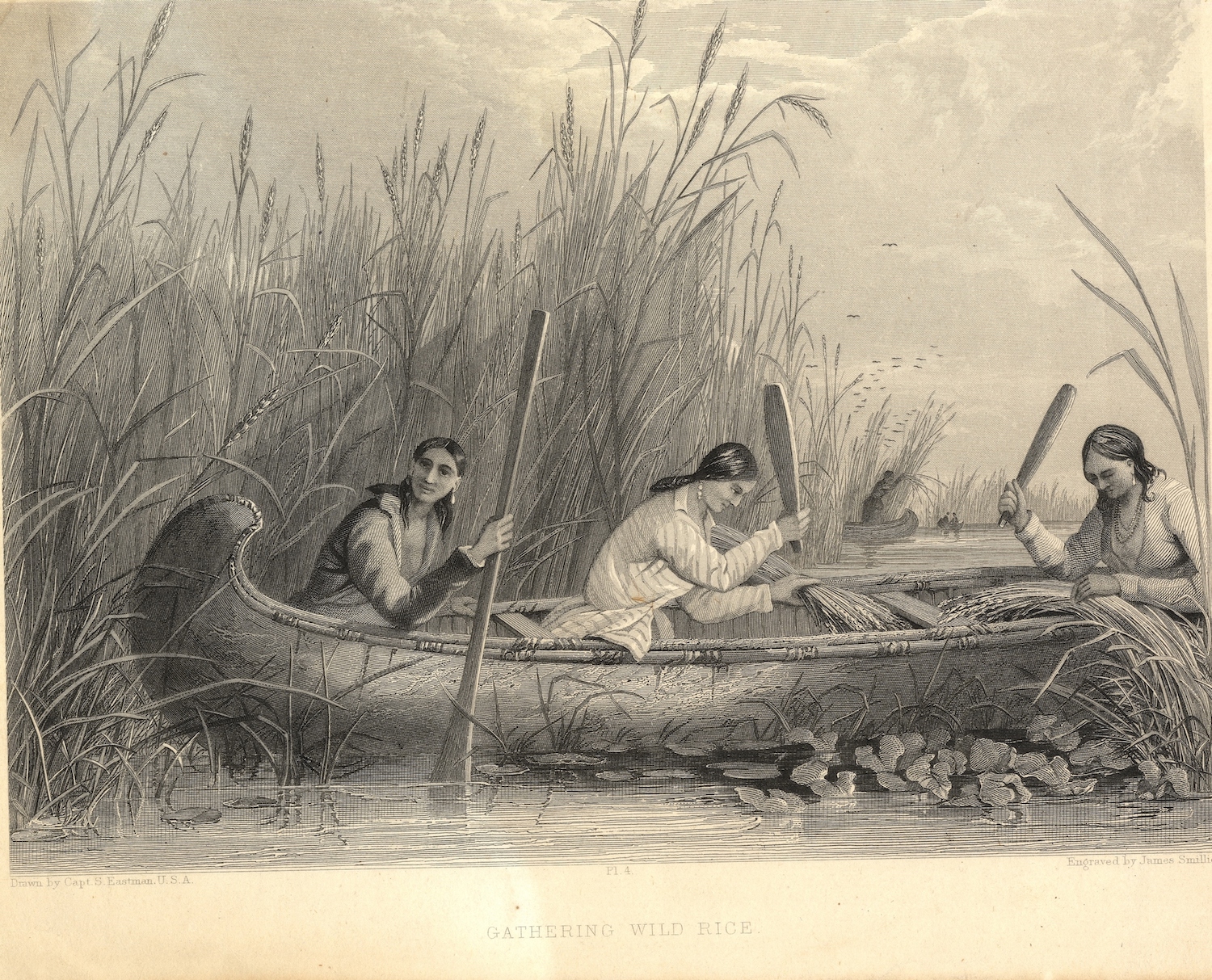

The site of Milwaukee may have served as a neutral place where a mix of tribes gathered to trade and live together. Though each tribe maintained their own distinct cultural practices, village life for Milwaukee tribes generally followed a similar seasonal rhythm that continued well into the treaty era with the United States. During the cold nights and warm days of spring, sap flowed through maple sugar trees throughout the region. Families gathered to hold ceremonies celebrating the harvest of the sap and to process it into maple sugar used to flavor and add nutrients to foods. Spring was also a time of fish runs and preparation for small garden plantings. During summers, extended families gathered together in large villages to trade and for protection. The fall brought harvest season, particularly wild rice that was gathered in preparation for the long and snowy winters along Lake Michigan. Hunting for game that provided fresh meat for the community occurred throughout the year. In winter villages broke apart into smaller hunting camps. In addition to hunting and gathering, the Potawatomi grew large quantities of corn that they later exchanged with European and American traders. W.A. Titus’ early history of Milwaukee cites a letter from fur trader John Askin to Todd & McGill of Montreal writing that he would send his brother-in-law to “Millwakee as much on acct of the Corn to be got there as the Peltry.”[7] The confluence of three rivers, presence of abundant natural resources, and mix of tribes positioned Milwaukee as an ideal trading post.

The French Arrive

The first Europeans to see Milwaukee were the French. From 1634 to 1763, the French claimed the lands of Wisconsin as a legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery. It is difficult to identify for certain which Frenchman first reached the lands that became Wisconsin. Etienne Brule may have reached Lake Superior in 1622 or 1623.[8] Jean Nicolet was welcomed by the Ho-Chunk near the present site of Green Bay in 1634 when he paddled with seven Wyandot traders across the Straits of Mackinac. While Green Bay became an important location for Great Lakes tribes to trade with the French—thereby allowing Milwaukee’s importance as a trading post to lag behind—Milwaukee was still connected to the greater region through trade networks. Traders who paddled to the Straits of Mackinac arrived at the French outpost of Sault Ste. Marie. Anishinaabeg traders from Milwaukee likely sent their trade goods to Green Bay and onto to Sault Ste. Marie or across Lake Michigan to relatives in the Michigan region who then traded with the French.

In the very early 1660s, Rene Menard became the first Catholic missionary from the Society of Jesus (better known as Jesuits) in Wisconsin.[9] Then, a few years later, Father Claude Allouez established a mission at La Pointe on Lake Superior’s Chequamegon Bay before moving to Green Bay in 1669. In 1673 French trader Louis Jolliet and Jesuit priest Jacques Marquette embarked on a journey to find the South Sea via the Mississippi River. Upon reaching the Quapaw in Arkansas and learning that the Spanish maintained a presence further south, Jolliet and Marquette returned up the Mississippi and along the Illinois River. They portaged near the site of Chicago before returning up the coast of Lake Michigan and passed the site of Milwaukee on their journey to Sault Ste. Marie. The following year (1674), Marquette returned and camped at the bluffs of Milwaukee for four days in late November while on his expedition to establish a Jesuit mission among the Illinois.[10] Marquette’s camp was the first recorded European stay at the site of Milwaukee. Father Zenobius Membré, who in 1679 wrote the spelling as Melleoiki, provided the first European record of the name Milwaukee.[11]

Milwaukee as Trading Post

Between 1700 and 1780 Milwaukee’s reputation grew as a small trading post. French traders were the first Europeans to make repeated trading expeditions to Milwaukee. Crown-sanctioned French voyageurs received licenses to conduct trading expeditions among Native American tribes. However, it is more likely that Milwaukee was first serviced by French coureur de bois, runners of the woods, who were unlicensed independent traders. The Native American community at Milwaukee traded furs and foods like corn, wild rice, and maple sugar in exchange for European manufactured goods, including weapons, cooking utensils, and beads. Increasingly important to the trading networks between the French and Native communities were the ties of kinship that developed through marriages between Frenchmen and Native American women. Through these relationships, strangers were brought into a network of mutual support and obligation that facilitated trade and solidified alliances.[12] Trade arrangements between Great Lakes tribes and the French became a military alliance during the French-Indian War also known as the Seven Years War (1754-1763). While the British defeated France and claimed France’s North American territories, the ties of kinship that bonded French traders and Native communities in Milwaukee remained intact, complicating the relations between the diverse Native American populations of Milwaukee and the British victors.

British traders had already started to arrive to Milwaukee before the end of the war in 1762 even as Frenchmen including Laurent Ducharme continued to renew trading partnerships in the region. The presence of competing Europeans and the presence of several different tribes at Milwaukee created complicated political alliances. These alliances were tested during the American Revolution when many of Ojibwe, Ottawa, and Potawatomi throughout the Great Lakes joined with the British and fought against the Americans. However, following the Americans’ capture of Kaskaskia in 1778, a Potawatomi leader at Milwaukee named Siggenauk, (known by the French as Letoureau or Blackbird) traveled to meet with American George Rogers Clark at Cahokia to discuss a possible alliance with the Americans. Siggenauk joined forces with the Americans, and his Potawatomi band continued to harass British western movements throughout the war.[13]

When the British called for a general council of Great Lakes tribes to meet at L’Arbre Croche in 1779 to convince Great Lakes tribes to fight with the British against the Americans, the villages at Milwaukee refused to attend the council. The frustrated British commander at Michilimackinac, Colonel Arent Schuyler DePeyseter, in 1779 described the Native Americans at Milwaukee as “those runagates [renegades] of Milwakie—a horrid set of refractory Indians.”[14] In 1779 he sent the British sloop Felicity to capture Siggenauk. Rather than succeeding in this plan, the sloop stayed in the harbor while several Potawatomi paddled out and received a few gifts from the British but refused to turn in Siggenauk. The pilot of the Felicity, Samuel Robertson, noted that when he arrived at Milwaukee he was met by “3 indeans and a french man who lives at Millwakey.”[15] While Europeans vied with each other to solidify their claims, Milwaukee’s residents maintained their independence.

American Claims and Milwaukee’s Founding Mother

Following the defeat of the British in the American Revolution, the United States claimed the lands of Milwaukee although, in practical terms, it remained largely a Native space. Occasional French traders lived seasonally at the trading post, but no American forts were erected at Milwaukee during the colonial era. Between 1780 and 1790 the trader Alexander Laframboise arrived at Milwaukee from Mackinac. Laframboise routinely sent furs from the region to the trading posts of Michilimackinac and Detroit. He later sent his brother, Francois, in his place to continue the trade. However, Francois Laframboise was killed by the Ho-Chunk on the Rock River and trade at Milwaukee was limited until 1795.[16]

In 1795 Angelique Roy arrived with her husband Jacques Vieau (also spelled as Vieux). Roy’s father was a French fur trader and her mother a Menominee woman from Green Bay. Roy had extended family connections throughout Wisconsin, including Milwaukee, and her family connections, like many French traders’ wives, aided her husband’s trading ambitions.[17] Vieau traded continuously at Milwaukee from 1795 until 1818 for the British North West Company.[18] Roy and Vieau had twelve children, six of whom were born in their home in Milwaukee built on top of a bluff in present day Mitchell Park.[19] In 1800 Antoine Le Clair established his fur trading post on the north side of the Milwaukee River. But the beaver populations that propelled the fur trade drastically diminished in the 1800s. The traders continued to follow the furs west and by the 1810s and 1820s Milwaukee’s settler population declined.

During the War of 1812 most Wisconsin tribes fought with the British against the Americans; however, much of the Native American population at Milwaukee remained neutral. While the War of 1812 forced the British to official recognize American claims to the region, British traders continued to maintain a presence in the region. In 1817 the United States conducted a census of the Native American population at Milwaukee, noting that American Indians in the Milwaukee area were “renigadoes from all the tribes around them, viz., the Sacques, Foxes, Chippewas, Menomonies, Ottawas, Winnebagoes, and Potawatamies, estimated at three hundred warriors.”[20] The complexity of alliances and the mixed village at Milwaukee confounded Euro-American attempts to neatly classify the Milwaukee villages.

Arrival of Solomon Juneau

In 1818 Solomon Juneau arrived at Milwaukee and established the American Fur Trading Company. Juneau came to Milwaukee to work as Vieau’s clerk. He married Josette Vieau, the daughter of Angelique Roy and Jacques Vieau; this marriage strengthened Juneau’s ties to the region. In 1824 Juneau constructed the first frame building in Milwaukee. Soon after the United States embarked on a series of treaty councils with the local Native American tribes to force land cessions. On February 8, 1831 the United States forced the Menominee to cede all their claims to lands north and east of the Milwaukee. In the same year Juneau became a naturalized United States citizen and on August 31, 1831 the first lands in the Milwaukee region were officially offered for sale at the land office in Green Bay. The Potawatomi ceded their claims to lands south and west of the Milwaukee River in the 1833 Treaty of Chicago and in 1834 the Milwaukee region was fully surveyed for sale to settlers.[21] While the United States attempted to remove Native Americans from Milwaukee, tribes persisted in maintaining a presence in their homeland. It is a presence that continues to this day represented by the current Native American community of Milwaukee.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Margaret Noodin, “Gitenimowin at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee,” ojibwe.net, accessed October 20, 2017.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 1.

- ^ Paul Radin, The Winnebago Tribe (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1970), 28-36; Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 3.

- ^ Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815 (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 11-15.

- ^ Michael A. McDonnell, Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2015), 29-33.

- ^ Heidi Bohaker, “‘Nindoodemag’: The Significance of Algonquian Kinship Networks in the Eastern Great Lakes Region, 1600-1701,” William and Mary Quarterly 63, no. 1 (2006): 30-31.

- ^ W.A. Titus, “Historic Spots in Wisconsin Early Milwaukee: A Polyglot Village that Became a Metropolis,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 10, no. 4 (1927): 428.

- ^ Alice E. Smith, The History of Wisconsin, Volume I, From Exploration to Statehood, ed. William Fletcher Thompson (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1973), 6-8.

- ^ Louise Phelps Kellogg, The French Régime in Wisconsin and the Northwest (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1925), 146-147; Smith, The History of Wisconsin, 16-29.

- ^ Smith, The History of Wisconsin, 27-32; Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 6.

- ^ Titus, “Historic Spots in Wisconsin Early Milwaukee,” 425.

- ^ Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 4.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 11.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1965), 6.

- ^ Titus, “Historic Spots in Wisconsin Early Milwaukee,” 427.

- ^ Titus, “Historic Spots in Wisconsin Early Milwaukee,” 428.

- ^ John Boatman, “Jacques Vieau: A Son of Montreal and a Father of European Wisconsin—Another Perspective on the French and Native Peoples,” Wisconsin’s French Connections website, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay Library, accessed October 20, 2017.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 13.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 13.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 6.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 20.

For Further Reading

Clifton, James A. The Prairie People: Continuity and Change in Potawatomi Indian Culture 1665-1965. Lawrence, KS: Regents Press of Kansas, 1977.

Gurda, John. The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999.

Loew, Patty, et al. Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal, 2nd ed. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2013.

Smith, Alice E. The History of Wisconsin, Volume I: From Exploration to Statehood, edited by William Fletcher Thompson. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1973.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.